A boy who fell in the snow. Øvresetertjern, 1967 | Paul Andreas Røstad, Norsk Teknisk Museum | CC BY-SA

To be an artist is to fail, as no other dare fail.

Samuel Beckett

In this image-obsessed culture, where the ideals of beauty and perfection have been taken to the extreme, what role does failure play? Although we seem to have less and less tolerance for error, our errors also humanise us, break down conventions and norms, and mark out new paths towards innovation. Courtesy of Turner and Nero Editions, we’ve published a segment of Valentina Tanni’s book Memesthetics. The Eternal September of Art.

One point where historical performance art intersects with the wild performance art of our own times is the investigation of the concept of failure. Online, the notion of failing is omnipresent, explored both in its lightest, most playful sense and on a more profoundly existential level. This term—like its intensified form, epic fail—is used to denote a situation of unequivocal defeat, a failure so ridiculous or resounding as to become spectacular and thus turn into a kind of inverse victory.

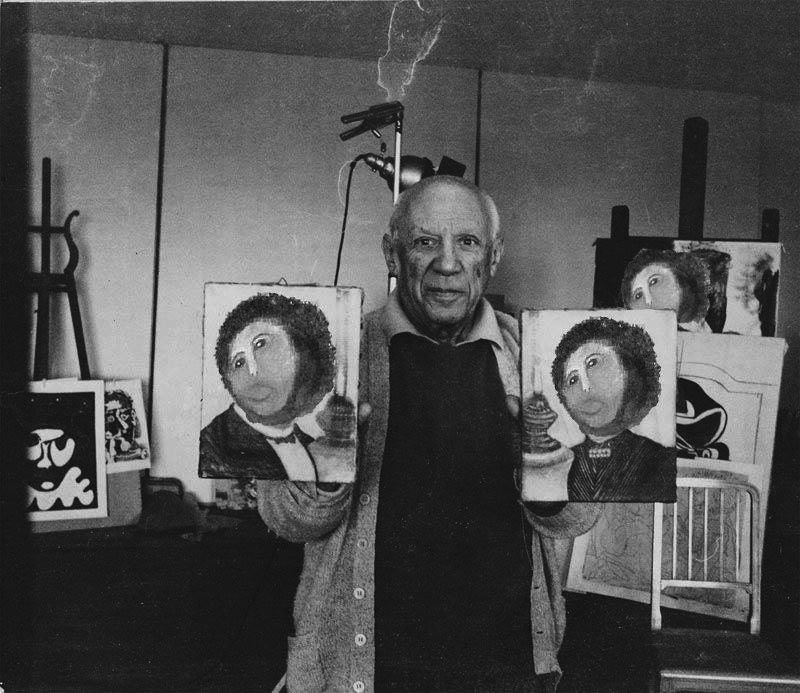

Take, for example, the most famous epic fail in the history of the internet: the clumsy restoration of Borja’s Ecce Homo by the elderly parishioner Cecilia Gimenez, which made headlines in 2012. Here, the enormous gulf between expectation and reality—Christ was made to resemble a kind of monkey—took the very idea of error to the next level. The ineptitude was so emphatic, and the final image so deeply preposterous, that the case and its protagonist became veritable icons of failure on an international level. Derision and embarrassment ended up being sublimated into a glorification of incompetence, here expressed in such a striking manner as to become paradigmatic.

Pablo Picasso and Borja’s Ecce Homo, found image

Online, fails are falls, blunders and destruction in the vein of America’s Funniest Home Videos, but they also include examples of sophisticated humor, in which error and flawed execution become techniques for exorcising the contrived perfection of mainstream culture and the obsession with self-curation typical of social networks. It is no coincidence that one of the most widely used meme templates is expectations vs reality, which highlights the difference between an “edited” version of life and a more genuine, authentic, imperfect one.

Failure thus becomes symptomatic of humanity and can, at times, also lead to discovery. As history teaches us, innovation and originality are often the children of error; uncharted territory is only reached by taking the wrong path. Artists, who know this well, have long deployed error, chance and unintended use as tools of research and production. “Art comes out of failure. You have to try things out. You can’t sit around, terrified of being incorrect, saying ‘I won’t do anything until I do a masterpiece,’” John Baldessari advised his students.

Failure is bound up with subversion, anarchy, the liberating joy of toppling hierarchies, rules, conventions. It can also be planned and therefore expected as the inevitable consequence of an overly difficult or impossible action. This is true of many works by Bruce Naumann, Gino De Dominicis or Francis Alÿs, where actions are repeated again and again, and the inevitable failures documented as rigorously as a scientific experiment. Alternatively, the act of failing can literally be staged, as in Bas Jan Ader’s performance series Fall (1970-71). Here, the Dutch artist, whose work centered on the theme of defeat, films himself in the act of falling: he rides his bicycle into a canal, slips off a roof together with the chair he’s sitting on, lets himself fall into a creek after dangling off a tree branch. In Fall, Ader demonstrates the fragility and vulnerability of the human being simply by succumbing to the force of gravity—a banal, everyday, potentially fatal threat. His tone, however, is always tragicomic, moving along the borderlands between dark humor and the ironic rudeness of slapstick.

The performative meme Falling, which was especially popular around 2011, is based on the same principle. Here, falls are sought out and exaggerated. Unfolding in public spaces (the street, the supermarket), in front of accidental audiences, they become events that disrupt daily routine by theatricalizing the stumble.

In the work of Maurizio Cattelan, who uses objects, installations and performances to explore his own performance anxiety, the staging of failure functions like an exorcism. Failure is also incarnated in Fischli & Weiss’s hybrid objects, which are veritable monuments to dysfunction. On JODI’s websites, failure turns into technological terror, the collapse of code becoming a metaphor for the increasingly problematic relationship between human and machine.

On the internet, technological error is omnipresent, both in its accidental version— a failure that can be ascribed entirely to the machine—and in the version that implies the machine’s improper use by humans. The former category includes glitches, accidental image distortions resulting from a software error, which have given rise to an actual genre known as glitch art. There is also the panorama fail, defined by the site Know Your Meme as “a sequence of photographs that have been poorly stitched together with panorama creation software, often resulting in a bizarre, artistic or humorous image.” In order to create panoramic photos, smartphones need to be moved in a certain way, maintaining a constant speed and distance, with all the elements in the frame remaining immobile. When one of these conditions comes to lack, the final image ends up being distorted, creating surreal visions, deformed creatures, futuristic landscapes.

Closely related to the panorama fail is the Photoshop fail: a disastrous use of photo editing software that culminates in the unintentional production of an absurd or ridiculous image. Here, as in Borja’s Ecce Homo, hilarity ensues from the dizzying distance between aim and result. Body parts disappear or are unnaturally elongated, collaged fragments fail to match up, objects and people are inadvertently deformed. The attempt to align one’s image with dominant aesthetic canons—which is the driving force behind most of these fails—ends up byproducing an infinite series of monstrous apparitions.

Half Cat, found image

One of the many mythological creatures birthed by these manipulations is Half Cat, a feline endowed with only a head, a tail and back legs, immortalized while out on a walk. Although the image was initially attributed to a panorama fail produced by Google Street View cameras, an investigation by Imgur and Reddit users in 2013 revealed it to be a deliberate edit, created by splicing together two separate images. The original photo, which was found and later published in an article in the British daily The Independent, actually shows a very normal white cat walking on a street in Ottawa, Canada. Nevertheless, the cat’s “halved” version, by now a classic of the surreal memes genre, became so well known that a Japanese online shop felt compelled to produce a three- dimensional keychain version of it—a disturbing gadget that sold out within a few weeks and itself went viral on thousands of blogs and social media pages. Closely related to Half Cat is Long Cat, another impossible animal that, on the contrary, boasts no fewer than eight limbs.

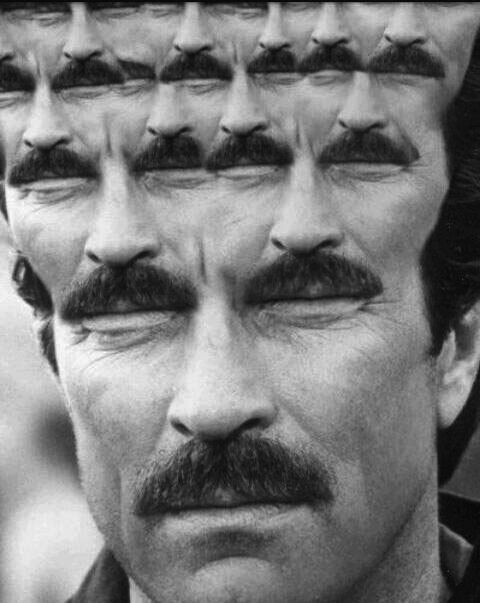

The taste for this genre of surreal image, achieved through simple photo editing, has a long history. Contrary to popular belief, photography has never been bound to a rock-hard realism: photomontage, colorization, superimposition and other special effects have been widespread since the mid-nineteenth century and have only proliferated since the advent of more advanced and accessible tools. Trick photography, in particular, became extremely popular around 1890, not only among professional photographers but also in amateur circles. László Moholy-Nagy’s Painting, Photography, Film, published in 1925, contains various examples of this genre, such as the image Horse Without End; a photo of a laughing man whose image is tripled by a distorting mirror; and “Superman” or the “tree of eyes.” A tireless advocate for the medium’s flexibility, the Hungarian artist saw photography’s transformation into a vehicle of “utopia and humor” as one of its many possible uses, offering these images as examples of the surrealist and genuinely comedic potential of the photographic image.

Tom Selleck fractal, found image

Alongside the accidental deformations, there are also intended ones—an enormous reservoir of images spread across so many genres, subgenres, traditions and trends that it would deserve its own study. In the late 1800s, photo manipulation was a niche hobby; today, it has grown into a mass phenomenon, not least thanks to the proliferation of software capable of simplifying the process, and in some cases even of automating it.

Leave a comment