Cho Cho The Clown with children | Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

Social media sites are often flooded with memes in the aftermath of tragedies, but lockdown took their role of providing social connection to a new level. While traditional media excluded humour from their handling of the pandemic, memes became a real-time narrative that allowed us to both explain and grapple with the crisis.

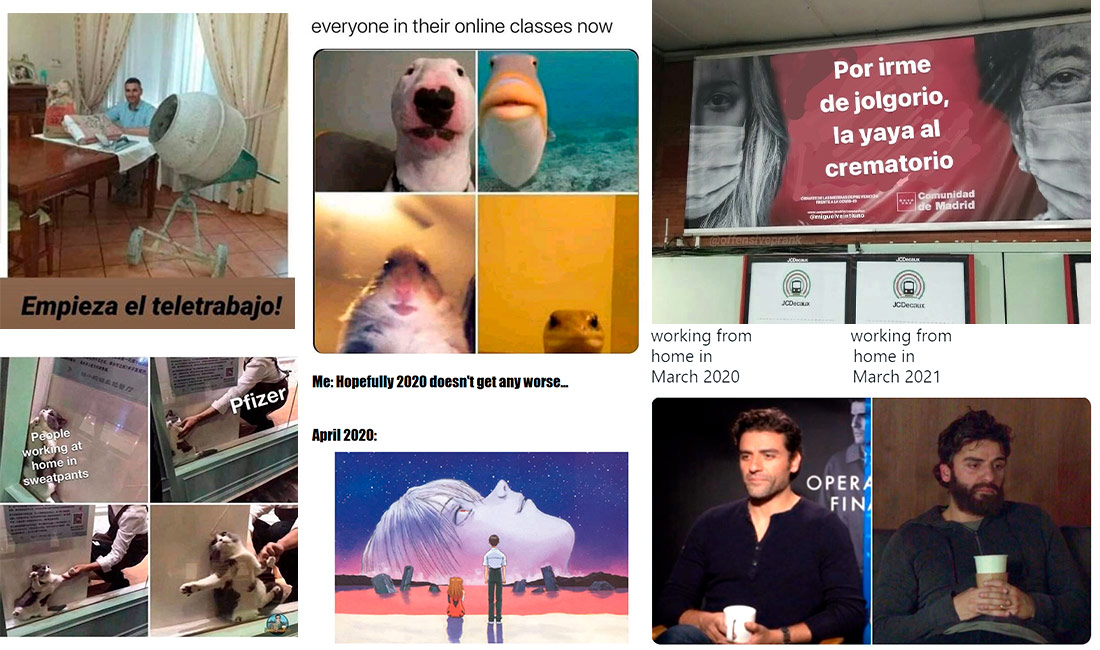

With COVID-19 leading to half a million dead and much of the world’s population locked down inside their homes, Google searches for the word “memes” reached a five-year high in April 2020. While the global situation was unprecedented, so was the popularity of these tiny bites of culture and people’s need to find and share them. A search for the term “coronavirus” on any social network at the time brought up an infinite number of results with these humorous images of the shared pandemic experience.

Over time, as weeks of lockdown turned into months, their format evolved. The collective humour shifted. Themes related more to living through lockdown – the implausibility of the situation, the need for social distancing, stocking up on toilet paper, the consequences of being at home (putting on weight and sharing space with children) and teleworking – gave way to more introspective memes. An exhausted Wojak saying “yes honey” became the embodiment of tiredness at having to deal with the same thing over and over again.

The peak of Google searches for the word “memes” coincided with the boom in searches for “COVID memes”, with three times the number of searches compared to the other most popular terms such as “cat memes”. The Internet is flooded with images that look the crisis in the face and laugh at it. We soon saw how something that was chiefly the ground of social media and internet forums, with millennials and zoomers at its epicentre, began to jump across generations through Whatsapp groups. Being cooped up at home, surrounded by screens, no one had anything better to do than be prosumers in the golden age of memes

Escapism from conventional culture

Strangely, people’s desire to see their own reality reflected in the content they consume did not apply in the same way to other cultural products – quite the contrary. During the pandemic, The Office became the most watched series (by far), turning the everyday life of a group of office workers into a small antidote to Zoom work meetings. For others, escapism meant going to live on a desert island to fish and water flowers, making Animal Crossing: New Horizons the best-selling Switch game of 2020 and putting it in the top 15 best-selling games of all time in just a year and a half. In literature, dystopian fiction saw its worst figures in 2020. According to a Penguin Books survey, more than 60% of respondents had no desire to read about COVID-19.

Karen E. Dill-Shackleford, editor of the academic journal Psychology of Popular Media, divides the population into two groups based on these same cultural consumption habits in traumatic times – active copers and passive copers. “Some people like to engage more with the news surrounding the pandemic because it makes them feel as though they have some control over it. Others cope through avoidance, and for them escapism is key”.

Humour for dealing with tragedy

A study conducted by Pennsylvania State University and the University of California, Santa Barbara concluded that memes helped people cope with the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite being essentially negative, as they dealt with themes such as death, deteriorating mental health or social isolation, subjects responded positively to them – even those suffering from anxiety about the pandemic.

For the mainstream media to portray the pandemic in humorous terms is a difficult task – a faux pas and could be perceived as distasteful by the public. There was a clear line between long-running TV series that chose to include the coronavirus in their plots, and those that did not: the former were mainly dramas (Grey’s Anatomy, This Is Us), while most sitcoms chose to situate themselves in a post-COVID or non-COVID utopia, probably because escapism is associated more with these lighter genres.

Humour, however, is intrinsic to the conception, production and distribution of memes; their degree of virality depends on it. In the words of Ioana Literat, a professor on the Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design programme at Columbia University: “Significantly, the context of the pandemic foregrounded the function of memes as a humour-based coping mechanism, and – by tapping into shared reference points and collective identities – as a means of social connection. (…) We found that memes that addressed the in-group, i.e. people or groups that viewers could identify with, were the most successful memes in terms of virality and user engagement.”

Silence, Brand!

Is it just the tone in which we tell things that makes memes easier to digest than the depiction of COVID in conventional fiction? Or is there something else that riles us when we watch films set in a pandemic world? When Michael Bay’s Songbird was released in December 2020, the critics were clear. A quasi-unanimous voice was quick to brand the film (set in a dystopia where COVID-19 has mutated into COVID-23) as exploitation of tragedy, and to give it the cold shoulder, leaving it with a 9% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and box office takings of $620,000 (a far cry from the $700,000-$2.5 million budget used to produce it).

The British newspaper The Guardian called this phenomenon “corona-sploitation”, accusing the film of trying to profit from the tragedy. Content created in a capitalist context will always be under the magnifying glass of opportunism; open to accusations of prying into our shared experiences, trying to generate an emotional response and to profit with (or from) them.

The dishonesty of market laws has little place in the participatory economy of memes. Yochai Benkler, a professor at Harvard University, places memes outside the market, noting that they “provide an enormously important counterpoint to the industrial information economy of the twentieth century”.

On the internet of memes, the echo of the intention to ban the commodification of emotions intensifies. The meme “Silence, Brand!” is used to jeer at brands when they try to gain sympathy and publicity by using a friendly tone to engage in digital conversations with other internet users. The phrase “Open your purse”, originally from @adamrayokay on TikTok, became a rallying cry, both on social media and in the protests following George Floyd’s murder, in the face of vague corporate displays of solidarity in the digital age. Internet communities have an increasingly critical perspective, making them an ever more hostile environment for those who want to cash in using the language and tools of their users.

Memes as a polyvocal narrative

The distance of cultural products from traumatic events that seems to be broken by memes is not limited to the pandemic. The first commercial film about the Vietnam War (1955-1975) was not produced until four years after the ceasefire, and even so, Apocalypsis Now (1979) was relatively early compared to other films that dealt with the tragedy such as Platoon (1986) or Full Metal Jacket (1987). Similarly, series such as Sex and the City or The Sopranos dealt with 9/11 by simply removing the Twin Towers from their opening credits.

As such, Memes are not only a form of entertainment and relief, but one of the most direct narratives of tragedy in times of crisis – not to mention the most honest representation of the emotional history of the pandemic. Polish linguist Marta Dynel, a lecturer at the University of Łódź, uses the word “polyvocal” to define the story they depict, and states that “memes can provide insight into current social and political issues, being vessels for public sharing of serious information and opinions”. Literat goes further: “COVID-19 memes also fulfill a vital meaning-making function, enabling the social representation of the pandemic via the processes of objectification, anchoring and identification”. Memes are thus poised to be essential pillars in the creation of truthful narratives in the traumatic periods of the future.

Leave a comment