Clown in the Springtime Tallahassee parade. Florida, 1985 | Deborah Thomas, Florida Memory | Public Domain

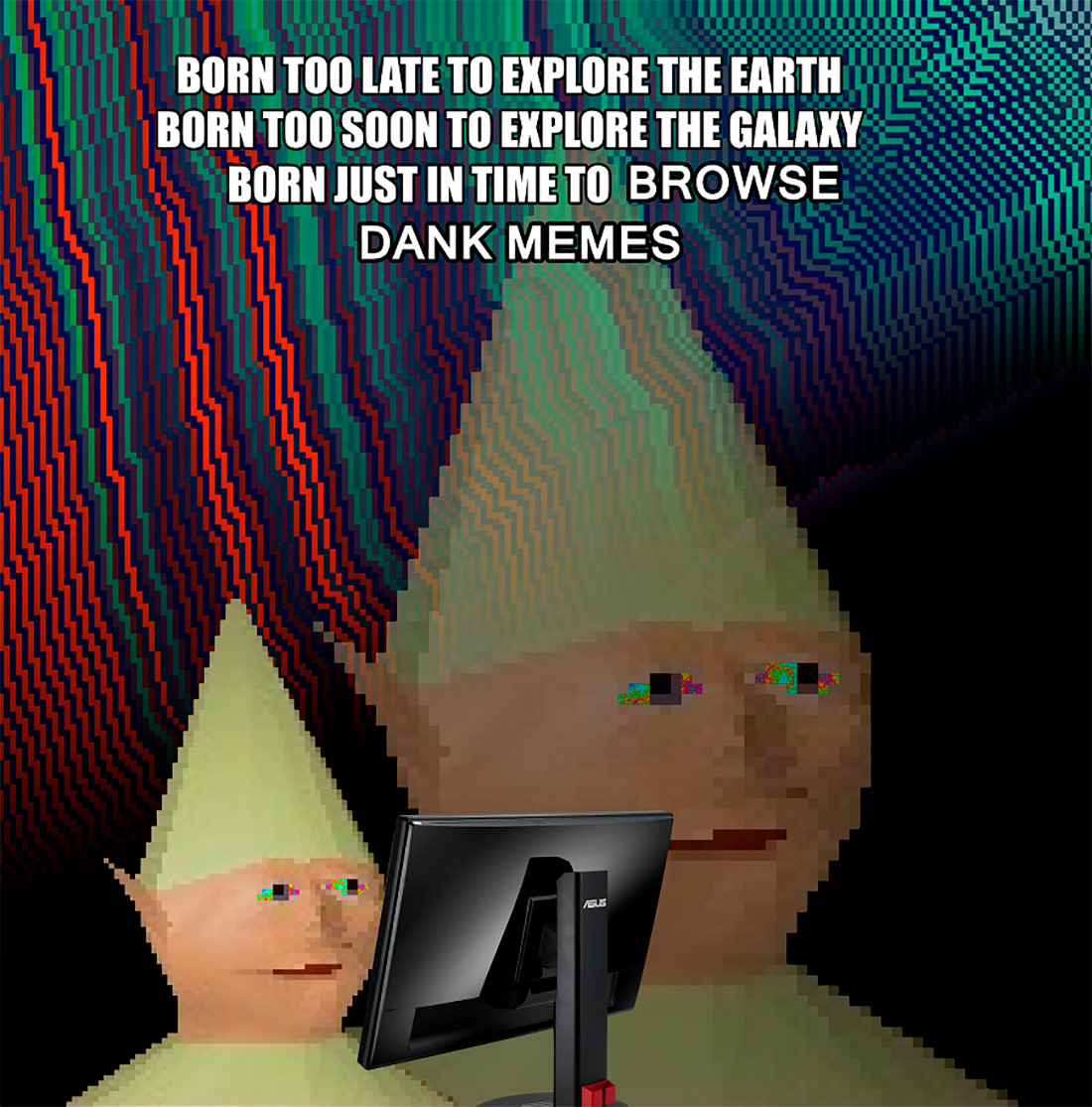

Dank memes are the anguished guffaw of the citizens of an Internet that is increasingly dark, dichotomic and brutal, an undecipherable language in times of algorithms, the creative saturation of the last Gaul stronghold of the Internet, entrenched and exhausted, fighting the imperial business model of Silicon Valley.

The word dank has three meanings: the first refers to the atmosphere of a dark, unpleasant, damp and cold place (like a cave or a dungeon); the second, in smoker’s slang, to the most pungent, sticky, high-quality marijuana and, according to the third meaning, dank is a way of saying that something is really good. Originally, saying that a meme was dank was equivalent to sarcastically saying that it was really good, in order to point out, precisely, that it had become too mainstream, or that it had exhausted its communication capacity (no longer understandable) or its humoristic capacity (no longer funny). But dank memes quickly became a genre of memes in themselves, which consciously used this exhaustedness as part of its own self-referential language and aesthetic. These were memes that talked about other memes, ironically imitating the errors of other memes.

The dank culture always sought the limit (self-awareness, self-reference and self-destruction), fleeing comprehension by the majority, avoiding digestion by the mainstream. Probably, this rejection of the majority was caused by the fact that while the dank meme concept gradually developed, the Internet was being invaded by the sickly-sweet and goody-goody tone of articles from BuzzFeed, numerous challenges and prefabricated chain messages, and above all, by the mass arrival of new users via Facebook. The Internet of social media networks. The famous 2.0.

To protect itself from this white and artificial Internet, the older and more experienced members of communities such as Reddit and 4chan built themselves a creative trench, based on absurdity, strangeness and mistrust towards any form of positive value or faith in humanity. Conspiranoia, tedium, anxiety and disdain were taking power in the active parts of many of these communities. YouTube series such as Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared and Asdfmovie illustrate to perfection this collective mood that, as argued by Rachel Aroesti in an article in The Guardian, considers that modern life is absurd and that there is no moral standard that makes much sense.

Even before the arrival of Trump, part of this frustration and mistrust inherent to Internet culture had generated a breeding ground that enabled the most reactionary, racist and misogynist ideas to be viewed as transgressive and attractive. As pointed out by Angela Nagle in her book “Kill All Normies”, this phenomenon was similar to the use of swastikas or references to Nazism by bands such as Joy Division and the Sex Pistols as tools for provocation and social transgression. However, in reality, where does this culture of strangeness and this frustration that is pushing digital creation towards darkness and tribalism come from? How have we returned suddenly to the first definition of dank, the one describing a dungeon or a cavern that is cold and dark?

From internauts to users

We often forget, when we make comparisons between the real world and the digital world, that if the world that we inhabit with our body were anything like the Internet of today, it would be a kind of Las Vegas casino: all the land in the hands of giant private corporations, a world without pavements, or hospitals, or squares, or governments… It would barely be a city made exclusively from advertisement-buildings that need our permanent, growing and anxious attention in order to survive and that, in exchange, are willing to offer us exhausting doses of euphoria, envy, sadness, boredom and excitement.

The creative and innocent freedom of the first Internet where we were not consumer-users but explorer-internauts is now just a distant memory. Back then, connecting to the Internet meant discovering a universe full of microbubbles floating in all directions. Now we don’t connect anywhere, we inhabit our digital identity in a permanent and passive way. Before, we navigated around small websites manufactured with little skill and home-grown, all of them just a crumb of their communication potential. The most exemplary reference of this diverse and heterogeneous Internet is GeoCities. These days we no longer navigate, we just open up the latest app or network to check whether we have any notifications.

Internet was a broad and heterogenous place, full of creative and naïve experiments, and there were real expectations of improving the life experience: a forum meant the possibility of universal warmth when you felt alone, receiving an email was as exciting as receiving a letter, and the pace of navigation did not allow you to go very fast, so everyone had time to write and read blogs. If we jump to the Internet of today, we will realise that the specialisation of the business model has converted the Internet landscape into a homogeneous space, without empty spaces between major platforms, with language and imagination abducted by giants who compete with each other to catch our attention.

Mice and algorithms

The social media networks seduce us, offering to facilitate communication based on the centralisation of the whole communication flow in one single space. Sean Parker, ex-president and founder of Facebook, has recognised recently that this promise of uniting the world hid another intention right from the very start: distracting us and exploiting our vulnerabilities. This hidden goal has become more explicit as, in order to keep us attentive, the platforms have evolved not to improve the free circulation of users and their messages but to increase their addiction and compulsive consumption.

Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook and Tik Tok have incorporated techniques and designs from the world of casinos – such as the elastic scroll gesture that emulates the lever of a slot machine. They have also discovered that the fastest way of grabbing our attention is by angering us or by making us feel envy or sadness. Specialisation takes on even more extreme forms with the increase of the use of algorithms that, little by little, gradually substitute our decision regarding what we want to do, see or consume. The timelines of social networks have gone from being the representation of our personal selection to hyper-optimised rivers of content that opaque processes decide for us. All we have left is the gesture: scroll and tap, scroll and tap. We are mice.

The most exaggerated case of this new phase is Tik Tok. The third largest social network in the world (500 million users) barely takes the users that you decided to follow into account. If the video that a user makes does not have a major impact among the first few users to whom it appears, the platform parks it and isolates it. It is noise. Make an effort to do something that is more fun ad attractive, it seems to tell you. What the platform ends up doing is accumulating attention in a few nodes that become viral and sharing out anxiety and isolation among the rest. This opaque control of what users see gives rise, furthermore, to new forms of censorship. Tik Tok, owned by a Chinese company, isolates political content or content that makes reference to the country’s hotspots, such as the protests in Hong Kong or Tibet.

Performative identity and self-deception

As explained by Jia Tolentino in The I in the Internet, the first essay in her latest book, Trick Mirror, the Internet has become a “self-deception machine” that bases its economy and infrastructure on the commercialisation of our personal identity. Tolentino says that “Identity, according to Goffman, is a series of claims and promises. On the Internet, a highly functional person is one who can promise everything to in indefinitely increasing audience at all times”. On the Internet we have come to say that we exist.

Tolentino uses the idea of sociologist Erving Goffman, according to whom identity is always linked to a performance. Our everyday interactions are based on the role that we play in front of others. For example, when we go shopping or we have a job interview, we offer a certain performative version of our identity, and the performance is transformed depending on the audience at any given time. When we go home, says Goffman, we are in the backstage area of our identity, where at last we can stop acting, and digest and rest.

Life has become an asphyxiating experience for many people because, according to Tolentino, the Internet breaks this ecosystem and forces us to constantly maintain, even if we are at home in pyjamas, the same never-ending performance for a massive and anonymous audience. The Internet has destroyed the backstage and the digestion. We never come down off the stage.

Magnification and saturation

Furthermore, the design and format of the spaces where we perform our online identity force us to exaggerate the message to attract attention and generate some type of reaction in our environment. Again Tolentino: “there is no engagement without magnification”. This idiosyncrasy alters the normal environment of interactions and causes everyone to be more predisposed, for example, towards becoming inflamed, feeling irritated or becoming indignant, as preferred ways of generating transit and attention.

Furthermore, to top it all, the deluge of notifications on our screens reminds us of the need to attend this performance without any stopper and destroy our minimum capacity to concentrate, to rest and to digest the stimuli that we receive. Against this vacuous horror of inputs and interactions, the alternative generated up to now, that of digital minimalism, is a response designed not to make our lives easier but to make us more efficient when it comes to working and not reducing our job performance.

RT ≠ endorsement

Finally, the forced adaptation of our ideas, political reflections and thoughts to the limitations of the formats of social media networks – stories that last 24 hours, hashtags that fragment every ideology into pieces, limitation of characters, structural censorship – hinders the propagation of complex ideas and nuances. Similarly, online solidarity has been substituted by a performative expression of solidarity, adapted to the logics of identity marketing: adding a ribbon to a profile, using the latest hashtag and retweeting viral political content have substituted the potential need to participate in a protest in the offline world. Even though it is true, despite everything, that the Internet offers an alternative to political action to anyone who, due to their status or the situation in which they find themselves, cannot participate actively in political action in the street, it is also true that online morality disincentivises, in general, any type of consequent political action to whoever it can.

That is not all, but rather this absence of has enabled far-right ideologies – which had become marginalised from social debate – to be deployed with greater ease, taking advantage of the speed of the interaction and the generalised frustration for introducing hate speech into the normality of digital life.

Dank

Against all this unliveable reality, dank memes can be understood, at the same time, as the expression that better condenses the spirit of our time and as an expression of fury that boycotts the marketing logic of the Internet: by making messages undecipherable and noisy, they are essentially anti-algorithmic. In their secret production and interpretation, they are neither tameable nor can they be sold.

Dank memes are the vanishing point and the Munch’s scream of a society exhausted with everything, with itself and with not being able to stop consuming and consuming itself, but that resists, cornered, through histrionic laughter. Exhausted with an Internet that had to be a universe of imagination and utopia and that has become an asphyxiating and unliveable place, that is not only conquering every corner of our everyday lives but that is becoming increasingly more inextricable from our way of feeling, thinking and wanting, from who we are and from why we will be remembered.

Blck | 21 November 2019

Com collons ha arribat això fins el meu escriptori de google? És genial aquest article.

Dani | 23 November 2019

Gracies! He pogut llegir força idees interessants al teu article.

La imatge del món real internetitzat m’ha agradat molt.

Al Barretto | 13 January 2020

Enriquecedor, y bellamente escrito!

Felipe Mapache | 03 July 2022

Debo reconocer que me fue un desafio leer el texto completo; desafio de continuar poniendo atención a un estimulo, dejando de lado las ganas sin sentido de pasar a la siguiente pestaña y encontrar ese mar de informaciones, historias, memes, novedades. Y el resultado fue gratificante, serán ideas que me quedarán rondando un buen tiempo.

Sin embargo, hay cierto aspecto que se me escapa de las manos. Al enfrentarme a esta tarea, encuentro pocos referentes de “ganadores” o si quiera “contrincantes” de tal desafio. Se vuelve una tarea solitaria, un nadar en contra de lo que considero “normal”. ¿Con quien comparto este sentimiento, esta experiencia?, pareciera ser una pregunta que siempre he aplicado a toda actividad, pero que se me hace evidente por la particular respuesta que obtiene en este contexto: me resulta difícil pensar en personas cercanas con las que pueda compartir este anhelo, esta realidad que se vuelve fantasía al no anticipar reciprocidad.

Leave a comment