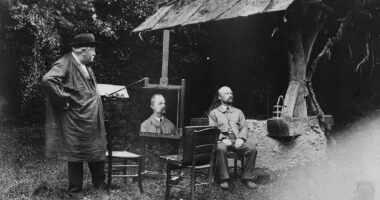

Painting class in school. Pennsylvania, 1937 | Library of Congress | Public domain

AI has landed with a bang in the field of creativity. Notwithstanding the debate about its ability to create art, this new scenario points to the possible implosion of human imagination: the homogeneity with which the machine replicates its creations is nonetheless a reflection of the way in which we produce images.

Last year saw the beginning of the global debate on the potential of artificial intelligences to replace human creativity. A significant fact here is that the uproar was about images. AIs had already been incorporated into economics, law, translation, journalism, medicine, transport and other essential spheres of our activity, giving rise to debates in specialised fields. But the emergence of good quality synthetic images triggered a cultural seismic shift which raises two considerations.

The first has to do with the atavistic reactionary panic generated by images that escape our critical and social control as manifestations of an “otherness”, of something strange, which individuals and groups must repress in order to perpetuate their consensus on reality. In What Do Pictures Want, W.J.T. Mitchell notes how, given the spirit of iconoclasm that today, as in the past, is only willing to approve of images if they act as mere reflections, images have the disconcerting ability to act as visages that return the beholder’s gaze. They have will, agency and desire, and a surprising capacity to generate their own dynamics with intelligence and intentionality.

Therefore, we can immediately infer that the images generated by neural networks such as DALL·E 2, Midjourney or Stable Diffusion, following more or less detailed prompts from a human operator, have a considerable potential to subvert the established rules of representation. In fact, what we consider to be one of the most suggestive aspects of synthetic images is that the imperfection to which they still succumb, and the inscrutable algorithmic reading of existing images, are producing an unsettling, weird and critical aesthetic that is lacking in the field of contemporary plastic, graphic and audiovisual arts.

This leads to a second consideration linked to the growing homogeneity of the images generated by humans; images that are no longer created with the purpose of freely expressing anything about ourselves and our relationship with our surroundings, about our imaginations and desires, but that pursue communication with others as a kind of post-photographic lingua franca, with all that this entails in terms of self-censorship. This is why, contrary to expectations, the ease of producing and editing images has not ushered in greater diversity in the visual ecosystem, but rather a suffocating and referential reiteration of motifs and styles that suggests the implosion of imagination.

We have already discussed elsewhere how this implosion is abundantly clear on Instagram, TikTok and other applications, although artistic expressions such as film and comics, whether mainstream or auteur, are by no means immune. We have only to go to festivals and fairs to see the extent to which the voracious production and consumption of images and the harsh panoptic under which they are created have created a hellish homogeneity.

An artificial intelligence generated image given the prompt “A photo of a robot hand drawing, digital art” | Wikimedia commons | Public domain

The result, as María Santana has pointed out, is that “the more we disregard imagination and desire, the more phantasmagoric things and bodies become (…) Our challenge is to delve into otherness, to let ourselves be questioned and unsettled by the Other.” Something which today, artificial intelligences have more chance of achieving than humans. In essence, the alarm that has been raised by visual artists is probably related to the sudden awareness that their work can be easily mimicked by AIs because it was already an exercise of fitting into the industrial-cultural complex.

Internet users seem to be well aware of this blindness on the part of artists towards the darker aspects of reality, aspects which they suffer in a world of ever more unstable and nightmarish characteristics. There is an overwhelming demand on the part of netizens in synthetic horror images, something that has resulted in the inevitable creepypastas as well as inspiring work such as the trippy illustrations of Jaesen Moreaux or the weird comic experiments of Brit Dave McKean and the Portuguese artist Ana Matilde Sousa.

These and many other creators are giving themselves the opportunity to converse with artificial intelligences (which, by the way, they often have to do without the knowledge of their peers to avoid a lynching), aware that, beyond the logical disputes around copyright and the exploitation of other artists’ work, we are standing before a revolutionary paradigm that is worth exploring. On the one hand, AIs are fantastic tools for expanding the consciousness of the artist and the awareness of their time, and even more so for deconstructing this awareness through the irrationality of the algorithm; as Jorge Carrión has said about the act of writing, “if the surrealists had fused with spiritualism so that the writer assumed the role of medium and invoked their ghosts, fears, memories and unconscious desires (…) we would now find ourselves in a similar transition: writing produced by machine learning and other forms of artificial intelligence is stamping a particular vibration on our times.”

At the same time, AIs offer a unique opportunity for (self-)demanding artists to question the meaning of their work in an audiovisual economy characterised by feedback and transience; by the antagonism between originality, homage and plagiarism which had, paradoxically, begun to fade in recent years; and by the ultimate impact of their abandonment to infographic tools that have affected the idiosyncrasy of their work.

We believe that plastic and visual arts are facing, as Brian Jackson has expressed it, an “existential crisis” given that we’re moving from a society that can’t look at things or create things in a visually sophisticated way to one that can. Jackson concludes, and we agree with his deduction, that a possible solution lies in a hybridisation between human consciousness and the unconsciousness of the machine that would project our human creative crisis towards unprecedented horizons for images.

After all, we must not forget that an artist worthy of the name is always immersed in doubt, in questions, in experimentation. They are on a journey, to go back to María Santana, of “the discovery and adventure of creation.” If this is not the case, their works will be little more than commonplaces, regurgitations of the spirit of their time. Precisely the faults we attribute to artificial intelligences.

Leave a comment