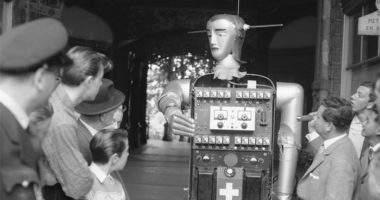

James Montgomery Flagg with a mannequin, 1913 | Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

The development of artificial intelligences (AI) capable of composing a tune or painting a picture is the outcome of research that ranges from the study of the human mind and its processes to the design of systems capable of replicating the cognitive mechanisms of the artistic brain. Disciplines as varied as neuroscience, information technology, art theory and philosophy converge in a path that takes us from the discovery of the spark of creativity to its replication in an artificial system. The future outlook of this work leads us to consider whether art will at some point cease to be considered an exclusively human activity.

Let’s cast our minds to the Industrial Revolution. The incorporation of machines into the production process showed, as with so many other events in our history, that Newton’s Third Law is equally infallible in questions outside the realm of physics: for every action on a body there is an equal and opposite reaction. And the action of automating certain repetitive processes in the textile factories was met by the Luddite reaction from less skilled workers who were entrusted with performing these tasks. Increases in employer profits led inevitably to the loss of many jobs, and that angered people. Hardly surprising.

The passing of the centuries has shown that this scenario has been repeating itself and affecting different spheres increasingly far removed from those initial repetitive tasks that anybody could do. Machines became more sophisticated and robots were born and became the focus of the main criticisms from a neo-Luddism that rallied against the incorporation of new technologies into our lives. However, everything pointed to there being certain types of work that would be impossible to replicate for these metallic gadgets. Human creativity was, like the village of Asterix, that little stronghold that the technological empire would be unable to dominate.

However artificial intelligences arrived and this concept that there is something purely human that a machine would be unable to emulate a machine became obsolete. Some of them beat us at chess. Others at go. And still others took charge of showing us that reading thousands of certificates to produce a medical diagnosis could be done in a question of minutes (although in this life nothing is perfect, my dear Watson). Each sphere of human creativity was invaded by AIs which day by day were doing things better. Even the world of art, that maximum expression of human self-realisation, discovered with surprise how engineers arrived with their little notebooks and started noting down their steps with renewed curiosity.

Prussian Class S 10 engine | Daniel Mennerich | CC BY-NC-ND

And so the artistic artificial intelligences were born. Complex systems that through learning techniques, neuronal networks and genetic algorithms started to imitate the work of painters, writers or musicians. To achieve this, their designers and programmers had to understand how a creator’s brain works and on what it bases itself to obtain results. This objective led them to the need to work in collaboration with neuroscientists and art theoreticians. Together they asked themselves the essential question: How does artistic inspiration arise?

From there they extracted a common factor that would serve both to write a story and to paint an oil painting or compose a tune: the artist feeding off the work of other artists. To paraphrase Picasso: good artists copy, great artists steal and artificial intelligences categorise into databases. Thus they put their AIs to work compiling the maximum information available on their area of creation. Shelley, an AI writer of horror stories, was fed full of works ranging from classic authors such as Poe to more contemporary authors such as Stephen King, as well as all the horror works available in the online public realm and even a collection of 150,000 stories from the Reddit channel Nosleep. Meanwhile Flow Machines, a musical AI, was given a ration of 13,000 songs, classified by styles. And The Next Rembrandt was presented with 168,263 pictorial fragments of the 346 paintings by the author from which it takes its name.

Once it has a good bookshelf of references behind it, the AI artist receives its commission. A picture. A story. A song. And that is where the algorithms with which they have been programmed – their genetic code – start functioning to develop the optimum result, or what amounts to the same thing, the completed work. Just as a human author does, the AIs conduct test after test comparing the results with the works that they know according to different parameters. With human help, or independently, they get closer and closer to their objective until the point where they consider they have reached the last iteration. And once the creative phase is completed, they express the result in the chosen medium.

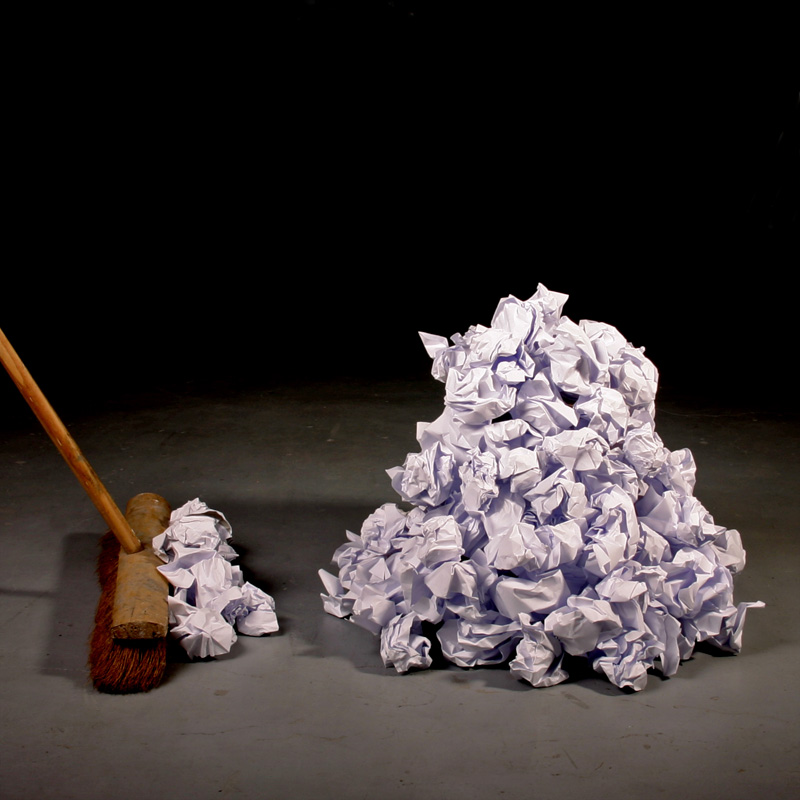

Creativity | Mark van Laere | CC BY-NC-ND

Observing the result of the work of these AIs is not far short of amazing, but we must not forget one fundamental point: these artists do not create as a result of a vital impulse or due to a need. Their art is not born of a specific poetic or of a proposal gradually refined over time. They are capable of imitating the creative process of the human mind but ultimately they do no more than fulfil the orders for which they have been programmed. We have managed to automate creativity and model its different parts, but we still need to be able to replicate that impulse that lies behind the first step of the artist.

Perhaps with the arrival of the Singularity this paradigm will change completely. Once AIs are capable of self-improvement and can transcend our own capabilities, then that artistic sensitivity that they are lacking today may emerge naturally from their silicon entrails. AIs will not produce art because they have been programmed to do so, but because they will feel like creating. They will feel the impulse of someone who needs to write to express an emotion or of someone who, if unable to paint, ends up irremediably withering away. Within their own private Maslow’s needs pyramid, they will be fast-tracked to the pinnacle of self-realisation.

The interesting thing about this event will lie in seeing how we are capable of reacting to these new forms of expression. We understand works of art – or at least part of them; therefore we have the usual controversies associated with contemporary art – thanks to the fact that we are human beings and our minds are constructed on a common scaffolding. We share, one could say, the same conceptual base which, however much it differs according to our training in the fine arts or in aesthetic theory, is housed in similar spaces: our brains. If art is a reflection of reality, all the artistic creations existing to date have been filtered by the same type of mind, the human mind.

The arrival of a new batch of artistic and self-aware AIs, in contrast, will offer us something never before seen: art conceived by non-human minds, based on their own creative impulses. And in the face of this situation I can imagine only two possible scenarios. In the most pessimistic case, we will be incapable of understanding art conceived by an AI. Our capacity for aesthetic reception would be surpassed. However, there is still room for hope. Perhaps in the future we will continue sharing cognitive schema with AIs that, ultimately, have been born out of our way of understanding the world. In that case, it may be that we are witnessing new forms of expression that stimulate our minds as never before. Works that expose any Stendhal’s Syndrome that has existed and will exist thanks to the intensity of the artistic enjoyment caused. Perhaps and only as a form of opposition to the many dystopias that exist, the future holds not a violent uprising of AIs but a revolution filled with beauty and art. Artificial intelligences whose aim is not to destroy, but only to construct. Ultimately, if an intelligence surpasses human capabilities, it is not too far-stretched to imagine that it might also ditch one of humanity’s greatest defects, right?

Ryan L Revoredo | 23 February 2019

Excelente artículo. Me gustaría agregar dos campos distintos, uno es la diferencia entre contenido de la comunicación artística (algo netamente humano y antropomórfico aunque puede ser imitado) y otro es el medio de la comunicación artística (digamos su gramática estructural que tiene mayor presencia de la IA). Otro campo importante es la diferencia entre la producción del arte (relativo a la experiencia y la sorpresa de la creatividad, puede ser simple e imperfecta pero igual funciona) y la transmisión del arte (depende de las interfaces digitales o físicas presentadas). La IA tiene distintos alcances en estas áreas.

Leave a comment