W.H. Hannam wireless operator, Cape Denison, Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914 | Frank Hurley, National Library of Australia | Public domain

The recent emergence of AI-based chatbots and image generators has reopened the debate on the introduction of new technologies into society. How will they be adopted in professional or educational contexts? What conflicts or tensions could they generate? Whatever the case, in order to address these questions, a collective debate is needed in which not only the companies that own these technologies have a voice.

Traduttore, traditore

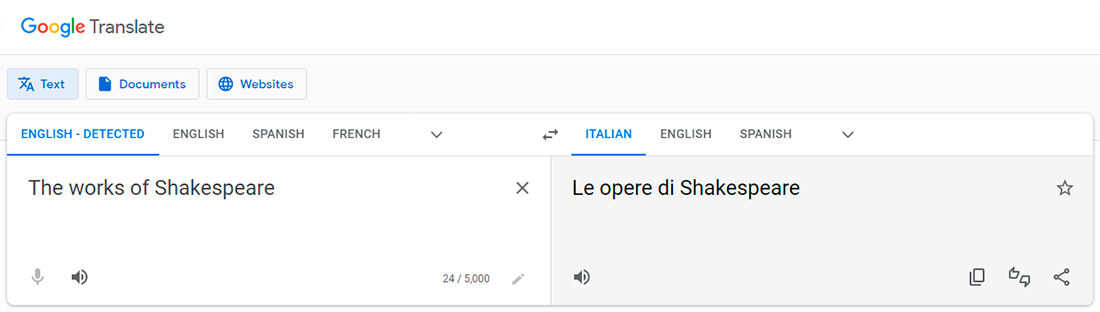

In Dire quasi la stessa cosa (Experiences in Translation), a compilation of lectures by Umberto Eco first published in 2000, the Italian semiologist talks about his experience with one of the first machine translation systems. Even though nowadays “running a text” through Google Translate is something people do every day at work or school, at the end of the 1990s these systems were just being launched and attracted the attention of intellectuals trained in the tradition of printed books. Not surprisingly, Eco’s curiosity led him to play around for a while with Babel Fish, one of the first machine translation applications integrated into the AltaVista and Yahoo search engines: around the same time, an image of the great semiologist wearing a pair of virtual reality glasses was doing the rounds in Bologna. Created in 1997, Babel Fish preceded by almost a decade the appearance of Google Translate, which has been available to the public since 2006. But let’s follow in Eco’s footsteps:

I accessed the automatic translation system provided by AltaVista on the internet (called Babel Fish). I gave it a series of English expressions and asked it to translate them into different languages. Then I asked AltaVista to retranslate the expressions back into English (…) Here are the results:

(1) The Works of Shakespeare → Gli impianti di Shakespeare → The plants of Shakespeare

Eco analyses the translation:

Babel Fish undoubtedly has dictionary definitions in its ‘mind’ (if Babel Fish has a mind of any description), because it is true that the English word work can be translated into Italian as impianti (installations) and the Italian impianti can be translated into English as plants or systems.

What is the problem with Babel Fish? According to Eco:

Babel Fish is not endowed with a vocabulary that includes contextual selections. It may also be that it has received the instruction that works in literature means a series of texts, while in the technological context it means plant. But it is not capable of deciding whether a phrase that mentions Shakespeare has a literary or technological context. In other words, it would need an onomastic dictionary stating that Shakespeare was a famous poet. The difficulty may be due to the fact that is has been ‘fed’ with a dictionary (of the kind used by tourists) but not with an encyclopaedia.

The passage from “dictionary” to “encyclopaedia” is fundamental in Umberto Eco’s interpretative theory: it is not enough to know the meaning of each sign in order to understand the meaning of an expression. The “contextual selections” place us in a constantly changing open semantic network formed by a dense web of redirections. If a dictionary is unidirectional (A > B), an encyclopaedia, on the other hand, works like a network of rhizomes – a sort of tropical jungle whose exploration requires a huge cognitive effort, one that the first machine translation applications were not able to simulate. In other words, the first automatic systems thought in “dictionary mode” and translated one word at a time.

A quarter of a century later, and after millions of interactions with humans and computational optimisation processes (in 2016 Google Translate introduced its Google Neural Machine Translation (GNMT) system, a program that mimics brain connections), automatic translators have learned to work in “encyclopaedia mode” and, although they are still far from achieving the precision we would all like, they are increasingly capable of understanding the contextual subtleties of linguistic exchanges. At the moment, Google Translate understands that “works” refers to Shakespeare’s plays rather than impianti (installations):

Why mention those first automatic translation systems? Why appeal to semiotic discussions from twenty-five years ago, when the hot topic of recent months is artificial intelligence and its capacity to generate texts and images? Because it is likely that, very soon, and as has already happened with automatic translators, text generation apps will be installed in our devices and integrated into the software we use every day. Microsoft’s interest in OpenAI (or to be more specific, its $10 billion investment in the company), the company behind the hugely popular image generator DALL·E and the conversational chatbot ChatGPT, is no coincidence. Notwithstanding the theoretical debates, the worried conversations in the corridors of educational institutions and the noise on social media, text generation systems will soon be just another icon in the top bar of MS Word or Google Docs. The same could be true for image generation software: it is not out of the question that they could become integrated into existing software. Image generation systems such as DALL·E or Midjourney, or some close relative, should not take long to appear on the Photoshop menu bar.

The ghost in the education machine

The incorporation of this new type of disruptive technology (whether ChatGPT, DALL·E or Midjourney, to mention just the most popular ones) into educational or work processes is bound to be traumatic, and its adoption fraught with tensions and conflicts. At the moment, the debate is particularly heated in the field of education, where the presence of these technological actors will make it essential to redesign a whole range of processes inside and outside the classroom. Classic activities such as “reading a chapter and writing a summary” or “writing 1,000 words on the French Revolution” will have to be redesigned to exploit the capacity of artificial intelligence to process information and generate “raw” texts. Some specialists such as Alejandro Morduchowicz and Juan Manuel Suasnábar (in their 2023 blog entry ChatGPT y educación: ¿oportunidad, amenaza o desafío?; ChatGPT and education: opportunity, threat or challenge?) take a step further as they wonder:

Will it make any sense to set homework? Will teachers have to become inspectors of originality, trying to detect whether the tasks were solved by human or artificial intelligence? Will they have to come up with a different way of defining it? These are legitimate questions that add to the long list constantly brought up by technological innovations for the area of education. As usual, these are concerns that should be considered within a more general framework of reflection on the relationship (past, present and future) between technologies and schools.

From the point of view of teacher, text generation systems are a fascinating tool for designing lessons. Morduchowicz and Suasnábar asked ChatGPT for ideas on how to teach photosynthesis to first-year secondary school pupils from an ecological and gender perspective: the two education experts were “still smiling open-mouthed” after seeing the proposal made by a technology that, in evolutionary terms, is just babbling its first words.

The dark side of AI

All digital technologies are surrounded by a gaseous halo that invites us to consider them as an ethereal, almost immaterial entity. The very concept of “cloud” is a good example of this process of technological dematerialisation. As is well known, the “cloud” is a mass of cables, chains of processors, data storage centres, more cables and vast warehouses full of machines hungry for electrical power in order to operate and cool themselves down. In fact, quite the opposite of a volatile “cloud”.

Artificial intelligence is no stranger to this process of dematerialisation. In Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence (Yale University Press. New Haven, 2022) Kate Crawford points precisely to this material dimension of artificial intelligence:

Artificial intelligence […] is an idea, an infrastructure, an industry, a form of exercising power, and a way of seeing; it’s also the manifestation of highly organized capital backed by vast systems of extraction and logistics, with supply chains that wrap around the entire planet. All these things are part of what artificial intelligence is – a two-word phrase onto which is mapped a complex set of expectations, ideologies, desires, and fears.

Writing in the same vein as authors such as Jussi Parikka (A Geology of Media, University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, 2015), Jane Bennett (Vibrant Matter, Duke University Press. Durham, 2010) and Grant Bollmer (Materialist Media Theory, Bloomsbury Academic. New York, 2019), Kate Crawford’s atlas reminds us that every second of text processing or image creation has an irreversible impact on the planet.

What is more, the operation of artificial intelligence requires a human workforce that is treated just as unfairly, if not more so, than the riders who pedal to deliver a pizza on time or the people who pack boxes in Amazon’s distribution centres. These are the so-called “ghost jobs” (Gray, M. and Suri, S., Ghost Work. How to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston/New York, 2019). Supposedly cutting-edge tech corporations rely heavily on tightly controlled and poorly paid temporary workers. Due to pressure from venture capitalists to incorporate artificial intelligence into their products, some companies even hire people to act as chatbots and impersonate AI systems. In an article entitled The Exploited Labor Behind Artificial Intelligence (Noema Magazine, 2023), Adrienne Williams, Milagros Miceli and Timnit Gebru explain that

far from the sophisticated, sentient machines portrayed in the media and pop culture, so-called AI systems are fueled by millions of underpaid workers around the world, performing repetitive tasks under precarious labor conditions.

As I write (and you read) these lines, there are thousands of workers doing data labeling in front of a screen to categorise or rate images, videos or audio files. This is how intelligent machines are being trained – using humans as cognitive sparring partners. According to Williams, Miceli and Gebru,

data labeling interfaces have evolved to treat crowdworkers as machines, often prescribing them highly repetitive tasks, surveilling their movements and punishing deviation through automated tools.

Like the printing press, the train, transistors or any other disruptive technology, artificial intelligence opens up many points of conflict that go beyond the exploitation of labour, from the question of copyright of original sources to its use in predicting social behaviour. Companies such as Getty Images that manage large image libraries are already mobilising their lawyers to make sure they aren’t left out of the big business opportunity to come. But who will defend the rights of the authors of the millions of pieces of content shared on social media that AI processes to generate its own creations? Many facial recognition systems are fed by images from police files, with ingrained gender and racial biases.

In her Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford also mentions the desires and fears of Homo sapiens, which are not few in number. For example, the terror, born of Modernity, of being replaced by a new satanic technology.

Production and creation in the age of intelligent machines

Machine translation systems have not led to unemployment; on the contrary, some (although only some) professionals use them to produce a first, quick draft before putting on their glasses and going through the text in detail to catch all the subtleties and decide on the best “contextual selections”. Other professional translators refuse to open the URL https://translate.google.com/ and remain faithful to the traditional method. But it is undeniable that for thousands of people travelling around the world, these automated systems help to break down the language barriers in countries that are not necessarily remote. In the scientific field, I must admit that they have got us out of a tight spot more than once by producing a quick abstract translation for a congress that needed to be submitted within a couple of hours. But human intervention is still essential in all these cases, both in the production stage (you have to know how to ask good questions or, to put it in more technical terms, to generate good inputs) and the interpretation stage (machine-generated texts always need to be edited and polished).

In addition to speeding up the production of texts, Morduchowicz and Suasnábar believe that, as regards education, ChatGPT

is the missing link to connect the repositories of teaching resources that have been built up on the internet for several decades with the specific needs related to the daily tasks and lack of time of teachers (which cannot always be met by search engines or educational portals).

Rather than talking about “substitution”, we should start to think and act in terms of “critical integration” (as opposed to the “uncritical exclusion” that proposes, for example, going back to the pen-and-paper assessments of the 20th century). The fear of labour substitution is understandable, but when we analyse past transitions in detail, the processes emerge in all their complexity. For example, the invention of the printing press did not mean that the scribes copying manuscripts by hand in their scriptoria were out of a job. As I explain in La guerra de las plataformas. Del papiro al metaverso (The war of the platforms. From papyrus to metaverse; Anagrama. Barcelona, 2022),

it would be mistaken to speak of a war between scribes and prototypographers. Neither the available documents nor historians’ interpretations suggest such a conflict. According to the medievalist Uwe Neddermeyer, the transition from manuscript to movable type was a process with “no riots, no protests, no poverty, and no unemployment”. Eisenstein comes to the same conclusion in Divine Art, Infernal Machine: “professional scribes and illuminators […] were kept busier than ever, the demand for deluxe hand-copied books persisted, and the earliest printed books were hybrid products that called for scribes and illuminators to provide the necessary finishing touches”.

Rather than displacing humans, some argue that artificial intelligence could replace Wikipedia or the World Wide Web itself. This seems unlikely – systems such as ChatGPT or Midjourney are in fact fed by the content of the World Wide Web and other digital repositories. The web is the world’s largest open reserve of texts, and artificial intelligences will have to draw on it to extract the textual raw material they need to keep up to date.

Artificial intelligence is a powerful tool that will make tasks easier but, as Marshall McLuhan pointed out, it will also change the way we think and perceive the world. Just as television and the World Wide Web changed our understanding of time and space, artificial intelligence will reshape the way we approach problem solving and the search for answers to all types of questions. Many activities and processes in the life of Homo sapiens will be radically affected, and not only in the area of textual information. For this reason, the second worst thing we could do would be to take the ostrich strategy and pretend that nothing has happened, while the first worst thing would be to insist on returning to the past.

Finale

One of the most popular Umberto Eco memes circulating on social media goes like this:

The computer is not an intelligent machine that helps stupid people. It is a stupid machine that only works in the hands of smart people.

Just like translation applications, we Homo sapiens must also stop using our brains in “dictionary mode” and shift to thinking more and better in “encyclopaedic” fashion. Abandoning binary approaches (real versus virtual, analogue versus digital, utopia versus apocalypse, etc.) and linear cause and effect (if new technology, then mass unemployment) would be a first step in this direction. Understanding and facing the complexity involved in the irruption of a new technological actor implies a collective effort that, under no circumstances, should be left up to a handful of corporations alone. The experience of Web 2.0 – that apparently open and participatory space that ended up becoming a ruthless machine for the extraction and monetisation of personal data – is too fresh in our minds not to set the alarm bells ringing.

If digital life were a video game, we could say that our relationship with chatbot AIs is still at level 1. One day, the current parlour games (“Guess who wrote this paragraph?”) will go out of fashion and we will move on to another, much more challenging and entertaining level, where the automatic creation of texts will be permanently integrated into our productive and educational routines until it becomes invisible.

Anahí Mercedes Pochettino | 15 August 2023

¡Buenas tardes! Creo que lo se continuará empobreciendo es la lectura. ¿Para qué leer algo si la IA puede hacerlo? Sobre todo en textos ensayísticos.

Leave a comment