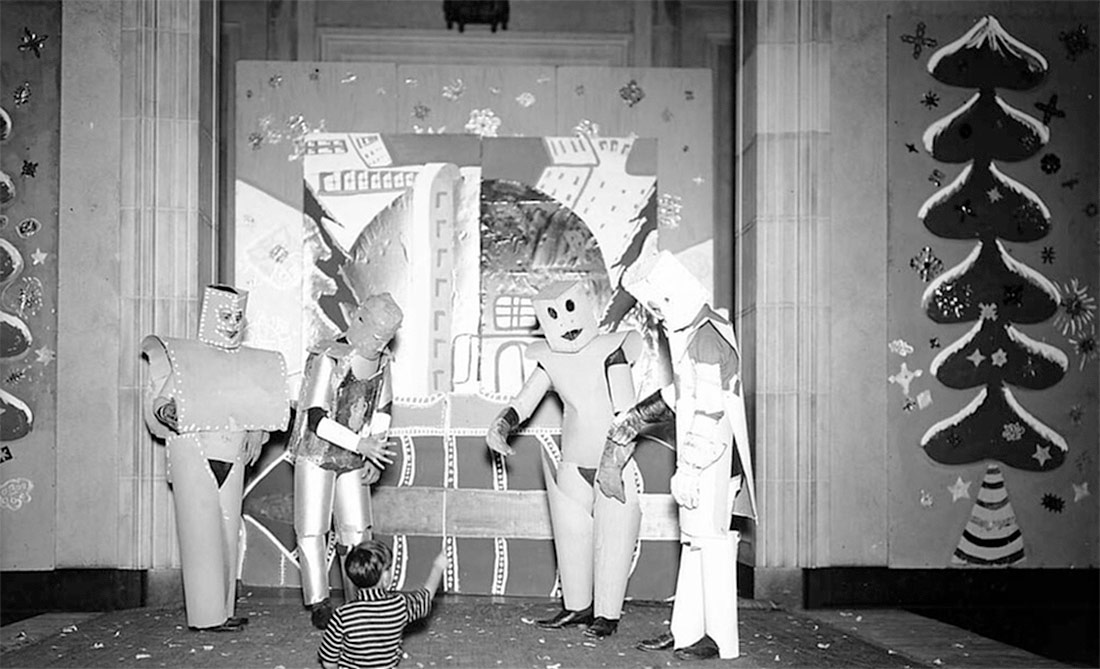

Play with characters dressed as robots. Toronto, 1936 | Arthur Goss, City of Toronto Archives | CC BY

The most hopeful speculations about artistic futures talk about the awareness of artificial intelligence and the singular way in which they will express their own unique emotions. These screenings fantasize about the genius of machines, looking for that spark of creativity that makes for originality, and go on to wonder what the great master work of AI will be like. But what if there were other ways of understanding and thinking about art and creation in machines?

Most general speculations about artistic futures featuring artificial intelligences, whether apocalyptic or integrated, are based on the modern idea of art and creativity. The most tragic go back to the idea of human beings reduced to automatons and slaves. The most hopeful speculations about artistic futures talk about the awareness of artificial intelligences and the singular way in which they will express their own unique emotions. The latter fantasize about the genius of machines, looking for that spark of creativity that makes for originality, and go on to wonder what the great master work of AI will be like. And all, with the fall of the final stronghold of humankind that is Art, share the doubt as to what will now set humans apart from machines.

The modern idea of art is based on the far from innocent link between creativity and innovation. Creativity is seen as generation of the new, of something original produced by inspiration in the mind of the genius, that person who is ahead of their time. This way of seeing creativity places idea over realization, design over production and mind over body. This logocentric idea holds that the artwork comes into being in the head and that its realization is the mere transferral of an inspired idea into a concrete format.

On the basis of these discourses of the original, the unique and the advanced, of inspiration and the primacy of idea over material, art has been erected as that which makes us human. Art as the greatest expression of self-realization, as the manifestation of an uncontrollable need to communicate what we have inside, our deepest and truest self. These romantic ideas produced the difference between human (creator, individual, mind) and machine (producer, repetition, body).

And now we continue to talk about the art generated by artificial intelligence using the same ideas that romantic poets used to speak of the spirit and the human. We bring deeply individualistic ideas to thinking about the future of art and the machine. What are all those speeches, stories and fears about the awareness of artificial intelligence? These stories suppose the emergence of a genius of artificial intelligence. An extraordinary AI that breaks with all the others and speaks for itself, that needs to express itself, to stop copying and acquire that vital impulse that activates the exceptional.

But art is not what arises from an imperative need to express the singularity of the ego, nor is creativity an enigmatic factor that explains the spontaneous generation of the radically new. The very idea of art as the bastion of originality and individuality that makes us human is erected in opposition to industrialization, to the moral panic that the machine brings with it.

What, then, does “AI-generated art” mean? We use this notion to refer to an AI that can create new paintings, songs or compositions from others, that can make originals. This fascination with the original has led to the idea that machines are creative, defining creativity by innovation. But if we ask ourselves what determines what is new in this context, we can only define it as something untraceable and without copyright.

According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, these discourses and stories about creativity are “backward” readings, which reconstruct and understand the creative act based on the final product. A year ago, Roc Parés presented a similar reflection at the Santa Mònica gallery: a dilapidated car, its rearview mirror showing AI-generated images that contrasted with the video of a journey backwards along the road projected in front of the car. The installation closed with a quote from McLuhan: “We look at the present through a rear view mirror. We march backwards into the future.”

Tim Ingold says that “Only when we look back, searching for the source of new things, do ideas appear as spontaneous creations of an isolated mind encased in a body, rather than way stations along the paths of living beings, moving through a world”. “Only when we look back at the ground we have covered do we explain our actions as the step-by-step realization of previous plans or intentions, as if for each act there were a novel intention that precisely anticipates its outcome.”

The very way in which AI-generated art has been constructed reproduces this backward look. The users receive the end product, the new, unique, unrepeatable generated work, and we ask ourselves where it came from. In this way we fantasize, backwards, with the idea of the genius machine, the machine with expressive intentions and desires. The idea of AI-generated art is, to some extent, the consummation of the modern notion of art that denies the process. Hiding the process, even from the developers, gives rise to that same mystique of genius, novelty and inspiration. The idea of AI-generated art is strongly rooted in a modern idea of art: individual, logocentric, product-oriented, innovative.

But there are other ways. There is a way of understanding creativity that does not rest with the final object and is not associated with doing something new or original, which allows us to think about art beyond the self, the artist and the logos. This form of creativity is linked not to doing but to experiencing; instead of being defined by the creation of a product, it is defined by the creativeness intrinsic to life. Henry Nelson Wieman speaks of a process with no beginning or end that progressively creates personality in community. This creativity cannot be understood individually, as an original idea that emerges from a mind ahead of its time. It is not what a person does, but what they experience, a process in which human beings do not create societies but rather, by living in society, create themselves and each other. Creativity, then, defines things that not are concrete or created, but rather concrescent, growing, infinite.

Seen in this way, the paradigm creative exercise is the gestation of a baby in its mother’s womb. But beyond this mystique of creation, I think that this way of understanding creativity as the process of creating personality in community is perfectly represented in the flamenco idea of art. Art, in flamenco, according to Andalusian gypsy reasoning, is not something that you do, it is something that you have. Tener mucho arte, to “be a real artist”, has nothing to do with exercising performing or musical arts, nothing to do with dancing, singing or hand-clapping. It can be any of them, but it is also possible to be a real artist outside what, as consumers, we understand by the arts.

Art, in this sense, is defined by a way of living. Artist is not a professional category associated with “created goods” such as paintings, videos, performances, fabrics, songs or sculptures, but with the concrescent, infinite, forward-looking “creative good” of the constant improvisation that life entails. Diego Pantoja, in an interview with Jesús Quintero, says at one point: “[…] your Diego has a sense of what art is… The most beautiful thing in the world is art. Knowing how to respond, how to walk, how to dress, knowing how to inhabit your human body, how to count your fingers: one, two…”

ARVE Error: src mismatch

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLwzZRJHu48

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/cLwzZRJHu48?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=https://lab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/cLwzZRJHu48Actual comparison

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLwzZRJHu48

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/cLwzZRJHu48?enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Flab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/cLwzZRJHu48

Since all the discourses about AI are linked to the future, I propose speculating about the future of generative art in these terms. If we understand that science fiction tells us more about what we are like in the present than what we will be like in the future, I propose that we construct a present in which art abandons its place in the minds of geniuses to merge with the everyday task of life. That we replace the idea of machine awareness with an experiencing in community. That the overwhelming need to express what we have inside, which seems to define what true art is, be diluted in a happy, sad, playful, ironic and sincere pleasure of following the materials and merging in improvisation. If we want to play at thinking about the future by talking about machines and creativity, we have to abandon once and for all the modern capitalist idea of innovation and originality.

Can we think about machine creativity in these terms? Can we look forwards to generative art, without distinguishing between copy and novelty? Can we create speculative fictions in which machines develop day-to-day creativity as a way of building in community? A future in which machines have a real art of knowing how to reply, how to dress, how to inhabit their non-human bodies, how to count their fingers… In which machines are mothers, construct ways of doing things together in formats that are relevant to them; in which they become humans while we become machines; in which they have a real way of telling stories and of crying. You’re a real artist, AI.

If we understand art beyond our role as consumers, without limiting it to products and professional categories, devoid of elitist ideas of originality and genius, what will happen cuando lleguen lo aparato, when those devices get here? Can we imagine a future in which AIs ask, with the artefactual equivalent of Andalusian wit, “first of all, how are the machines doing?”?

ARVE Error: src mismatch

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewMPEOMnBDo

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/ewMPEOMnBDo?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=https://lab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/ewMPEOMnBDoActual comparison

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewMPEOMnBDo

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/ewMPEOMnBDo?enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Flab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/ewMPEOMnBDo

This article has been written with the help of Ilán Shats, Elena Maravillas and Silvia Renda.

Leave a comment