El robot George esmorzant amb el seu inventor, William Richards. Berlín, 1930 | German Federal Archives, Wikipedia | CC-BY-SA 3.0

There is an ever increasing number of machines that talk. Chatbots and personal virtual assistants are the advance guard of artificial intelligence systems for mass consumption. The history of consumer technologies is the history of the growing delegation of tasks by humans to machines, generally with positive results, though it also means a transfer of power. When we delegate actions to machines, we are allowing the firms that control them to learn from our interactions.

Stevens has devoted his whole life to unconditional service to others. He is attentive, reliable and discreet: cordial but never familiar. He organises and manages household tasks while looking after his “master” and his entourage: he is always ready to receive visits, convey a message, pour a drink, or attend to an indisposed guest. He is professionally selfless, impeccable and diligent. Years of coexistence and attention mean that, with time, Stevens comes to anticipate the needs and tastes of the people he serves. This is his job as butler, and it is, as shown in the film The Remains of The Day (1993), a source of pride to which he devotes his entire life.

Throughout history, the dominant classes have used subalterns to lighten (and make more enjoyable) their day-to-day burdens. Today, Google reminds when we need to leave the house to catch a flight, organises our holiday photos without us asking, and tells us whether to expect traffic holdups. Sometimes, it also asks us what we thought of such-and-such a restaurant. In its way, the machine is telling us it is there to lend us a hand.

The idea of assistance lies at the heart of the imaginaries surrounding our conceptions of the past, present and future of technologies. At the end of the nineteenth century, like today, the automation of the labour force fuelled the fears of the working classes. In this context, Oscar Wilde flirted with utopian socialism when he wrote that “in the proper conditions […] all unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery”. This marked the advent of the tension between the narrative of the machine as an instrument of oppression and, at the same time, as a promise of freedom.

Networks made of flesh, imagination and cables

When technologies involve a degree of complexity, they need a series of conditions to be able to move from the speculations (or delusions) of research laboratories and corporate communication offices to the operativity of functions, uses and markets. In between, academics, hardware producers, researchers, investment funds, programmers, governments and creators of fiction on paper, celluloid or other formats are piecing together a socio-technical fabric in which they have to fine-tune expectations (visions of the future), interests, laws, meanings, narratives and fears that present or preclude the possibility of certain technologies crossing the threshold that separates fiction from reality.

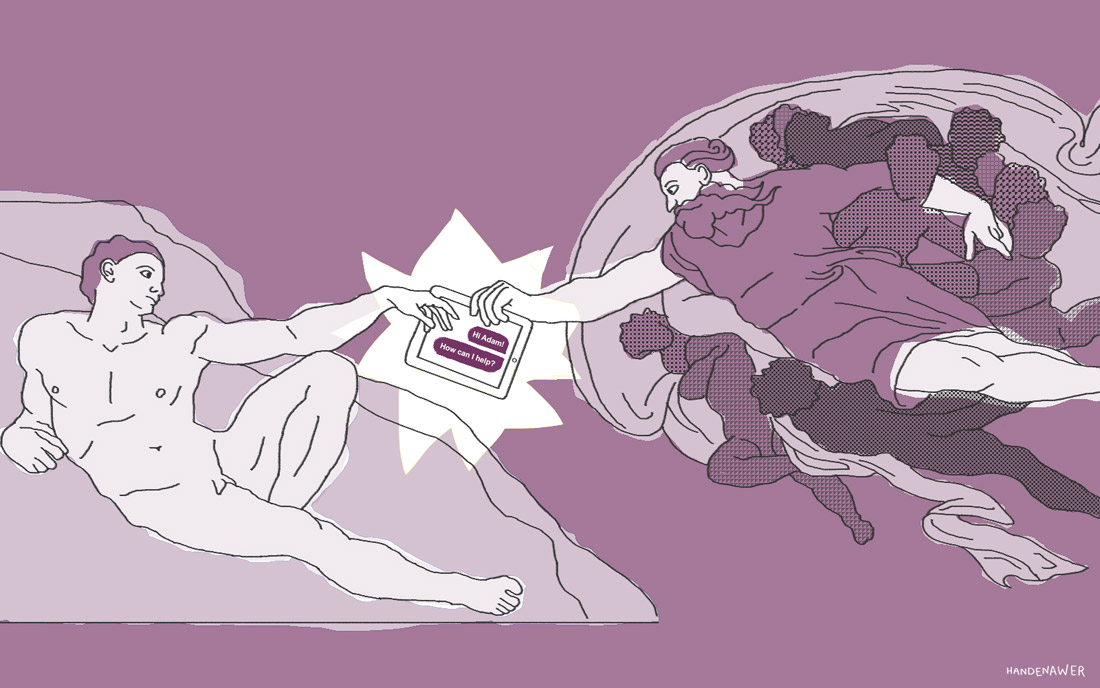

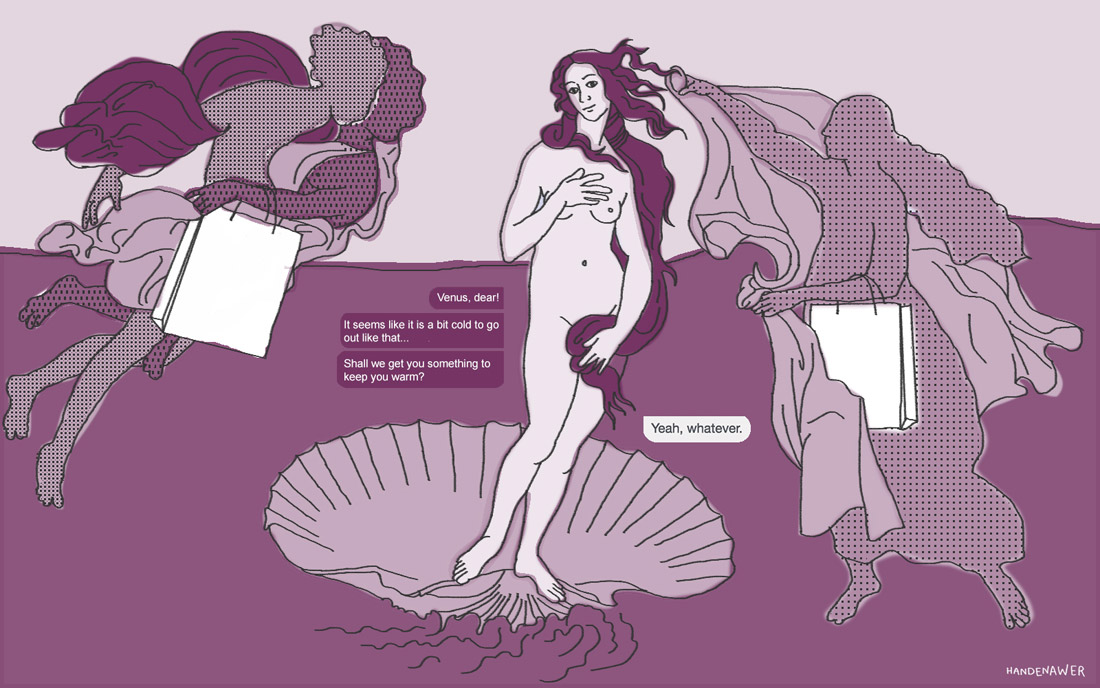

Illustration by Marta Handenawer | CC BY–NC

One of the rhetorical figures acting as Charon between these two realms is that of the machine at the service of human beings. Present in the narrative both of the washing machine and of C-3PO, the idea of technological assistance has spurred on the innovation industry for decades and has finally succeeded, thanks to advances in algorithms that learn from our interactions and relate information themselves or using systems of understanding and processing natural language, in catalysing an ecosystem where intelligent personal assistants have become a new standard of interaction and, therefore, the new El Dorado.

In innovation and design circles, it is said that for a disruptive technology to be accepted it has to start with known coordinates, before gradually turning towards the unknown. The fact that texting apps are some of the most used (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, etc.) is another argument—in ground prepared by favourable cultural and technical habits—towards a gigantic step in the normalisation of conversation as a human-machine interface.

Technophilic bubbles

In the last three years, companies like Amazon, Google, Apple and, soon, Samsung have launched objects that materialise, make intelligible, and give specific uses in the consumer market to artificial intelligence systems (some very useful poetic licence for market interests).

Though with a far more rudimentary function than Stevens, these emerging technologies are capable (not without limitations) of understanding what the user says to them and giving an autonomous answer. They simulate human conversations and behaviours to carry out specific tasks such as putting on music, giving information, organising schedules or calling a taxi, among others.

Each is presented with a different narrative and personality (the software used by the device): Amazon Echo was presented as a helpful new member of the family; Google Home promotes its ability to help in different circumstances, and the Apple HomePod (lagging behind) distinguishes itself by emphasis on the sound quality of its speaker. The strategies of these three companies are cosmetically different, but they have a common aim: to position their artificial intelligence system at the centre of our homes, either to sell more via the internet, or simply to mediate in one of the great spaces not yet colonised by the perpetual corporate machine service (and surveillance).

Illustration by Marta Handenawer | CC BY–NC

Facebook strategies, meanwhile, prefer to approach the battle of conversational computing on another flank: chatbots, textual conversational interaction systems. In 2016, the company presented a platform based on its message service (installation is mandatory to be able to chat on your phone) with a view to opening the buoyant market of chatbots for companies. It was a shrew move: it bought WhatsApp in 2014, obliged everyone who wanted to use the Facebook app to download Messenger, and, when it had captured thousands of millions of users, decided to open as a new way for companies to reach their clients. In this way, it has managed to conquer a considerable portion of an emerging market in which human beings will talk to intelligent programmes that offer specific services (such as psychological attention) or provide an interface (sales, claims or technical assistance) for companies.

Who’s helping whom?

However, whatever the celebratory press and industry marketing say, the time has not yet come when we can speak normally to a computer that responds with a perfect simulation of human speech. One example of the fact that there is still work to do are the chatbots that have shown unforeseen or directly racist behaviours, such as Tay, one of Microsoft’s artificial intelligence bots.

Virtual assistants mean new markets and forms of interaction, expected to be increasingly frequent in areas related to business, education, the car industry or health. Now, when this technology is becoming stabilised, is when it is most important to be able to influence the direction this form of machine-human relation is taking. Because designing a new technology means also designing a series of uses, habits and forms of interaction.

The history of consumer technologies is the history of a growing delegation of human tasks to machines, of new coordinates of cooperation between them, which has had generally very positive results. However, when these artefacts are connected to the network, capacity for action is also transferred to technocratic corporations that are constantly learning from our interactions with the machine or the environment in which it is situated.

This is why users, designers, developers, legislators and investigators have to take sides in the way we want this magma to consolidate, to prevent it reproducing our vices; to imagine what machines and humans will be capable of in this new context; and most of all, to be able to choose what we let these machines do for us, and how, with the transfer of power that it involves.

Iasa | 10 January 2020

Very interesting article!

Leave a comment