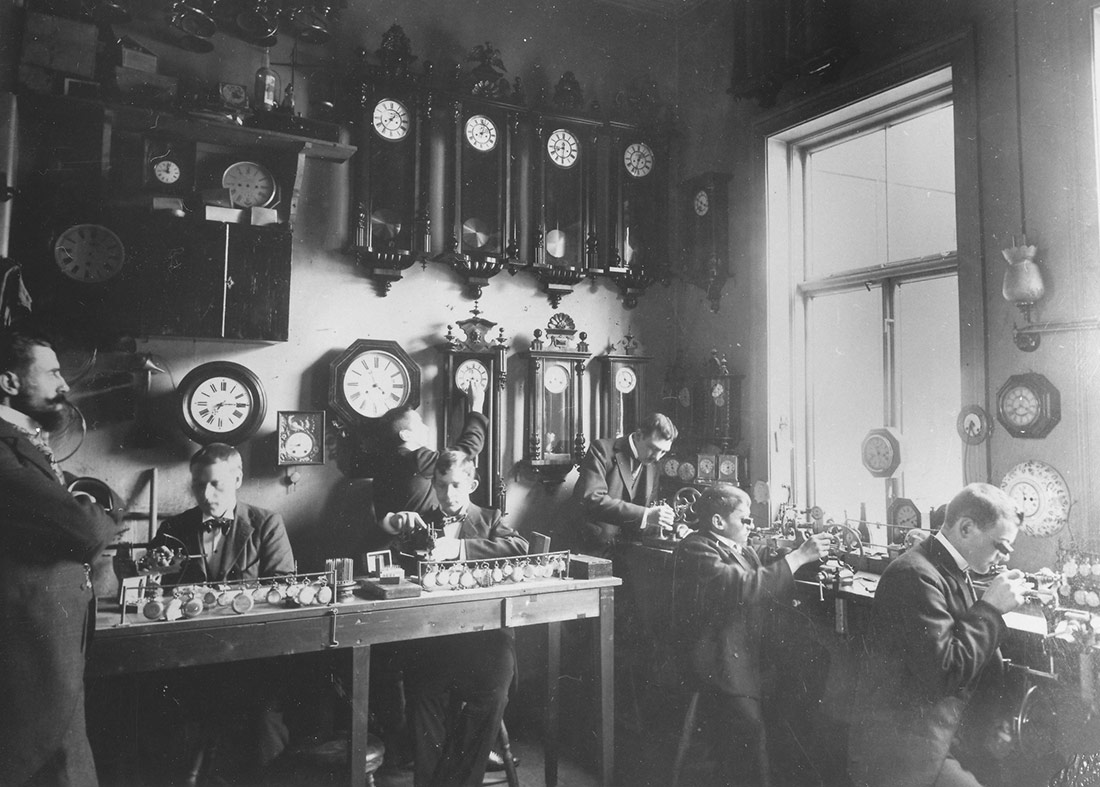

Watchmakers, c. 1900 | Municipal Archives of Trondheim | Public domain

Time is a physical phenomenon, although it is represented, measured and managed culturally. The idea of chronopolitics points to the politics of when: in what ways time is divided into certain units and based on what; what ways of experiencing and using time are considered normal and desirable (and which are not); and what modes of living, working, caring – and even existing – are made possible or impossible.

In Alice in Wonderland, the protagonist follows a white rabbit – always in a hurry, afraid of being late and constantly glancing at his pocket watch – until she falls down a rabbit hole that transports her to a dimension where reality is governed by a different set of rules. This figure also appears in the first film of the Matrix trilogy, where the white rabbit takes the form of a tattoo that Neo follows until he ends up at a party and finds Trinity, who introduces him to a group of people capable of jumping between the virtual and real planes.

In the first case, the portal between the two different planes is an animal burrow. The second is of a different type – infrastructural and distributed. In the Matrix, the virtual and the real worlds are connected by telephone lines that are hacked by humans using computer systems.

In 2009, a scientific article was published describing the characteristics of a prototype developed at CERN named White Rabbit. The purpose of the project, which has evolved since then, is twofold: firstly, rapid data transfer, and secondly, the generation of an ultra-precise synchronisation standard measured in sub-nanoseconds. This clock-network was born for purely scientific purposes and was shared open-source. Soon after, it was taken up by other technology-intensive industries, such as space, military and finance.

Standardisation, time and power

The technologies we use help us make sense of the world we live in, and in this way, in the background, they control the world we make with them. Calendars and clocks are parameters that tell us when we are. In a similar way, there are many other artefacts that situate us. In the 19th century, the telegraph served to synchronise the extraction of natural resources from European colonies and to coordinate their transport, manufacture and trade. From the metropolises, these lines of communication imposed a way of understanding time and nature on other cultures and worldviews. At the same time, the arrival of rail transport in new latitudes also saw the arrival of punctuality mediated by machines and the industrial organisation of life.

In this regard, sociologist Barbara Adam (Time and social theory. John Wiley & Sons, 2013) explains how the rational and synthetic measurement of modern time is necessary to convert days, periods and moments into units that can be bought and sold in the labour market, which is fundamental in the capitalist economy. This machine-time alienates human beings from natural rhythms and becomes a standard that can be applied at any time and in any place. It is an interchangeable unit with the power to separate that which is “developed” (i.e. further along a hypothetical straight timeline connecting the past with the future) from that which is not.

This standardisation also gives shape to a deeply rooted form of gender discrimination. As explained by sociologist Judy Wajcman (Pressed for Time. University of Chicago Press, 2014), the value of time is unequally distributed. “Time is money” in productive activities, generally associated with men in the context of the workplace, while the value of this time is invisibilised in reproductive and caring tasks, which, even today, are still largely carried out by women.

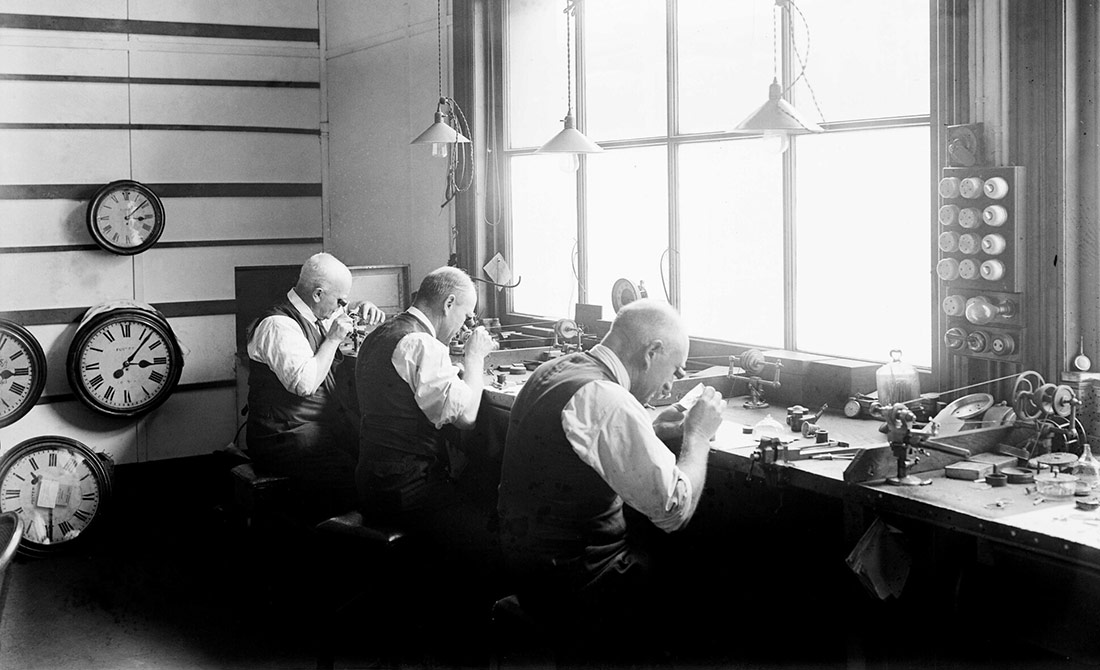

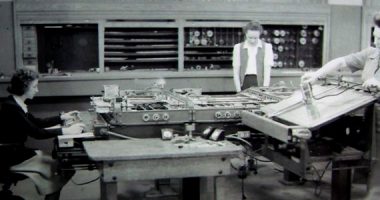

Watchmakers, c. 1930 | Public Record Office Victoria | CC BY-NC

Globalisation, networks and data in industrial chronopolitics

The imperialist dynamics of the 19th and 20th centuries paved the way for the creation of globalisation. After telephone infrastructures, road networks and maritime routes, information infrastructures were added to multiply the intensity and speed of movement of people, data and goods. The technological advances resulting from the world wars led to the development of a new, more accurate timescale, which in 1972 became the global standard: International Atomic Time (TAI). During this same period, the computer industry began to emerge, the first investment funds that would finance Silicon Valley were consolidated, and ARPANET – an early version of the Internet for university research and defence in the USA – came into use. This triangulation, in a context where the military budget, fuelled by Cold War paranoia, filled all kinds of R&D laboratories with resources, set the coordinates for a new chronopolitical era rooted in the temporality of the industrial revolution.

Modern-day technocapitalism would be inconceivable without the linear, sequential and causal understanding of time in industrial time, which laid the foundation for today’s predictive control technologies. Datafication systems require timestamping processes to establish when the data has been produced, which in turn is fundamental for machine learning and the coordination of different functions within a network.

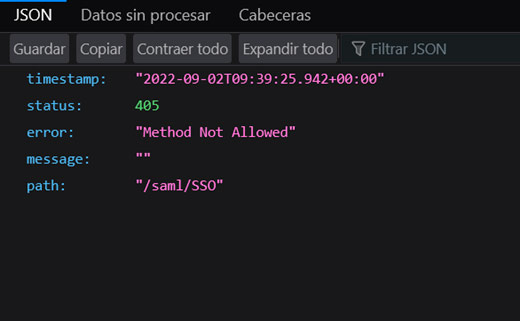

Example of timestamp

Computing, finance and speed

Also since the 1970s, the computer industry and the financial sector have evolved by feeding into each other. This can be put down to two factors: the first is the enormous amount and diversity of data managed by the financial sector in order to make its investment decisions and which, since the 1980s, has made it one of the main users of artificial intelligence systems. The second is the need to cut down the time between decision-making and execution of financial transactions. As having the highest processing speed and capacity can make a billion-dollar difference, the financial sector injects large flows of capital into the tech industry.

This is the background to race towards high-frequency trading, which has led to more than fifty per cent of financial market transactions now being executed by algorithms. The sociologist of knowledge and finance Donald MacKenzie (Trading at the Speed of Light. Princeton University Press, 2021) explains that the profitability of securities trading in this algorithmic market depends above all on trading speed. To achieve this, an infrastructural fabric needs to be built to enable such hyper-speed, requiring investment in the development of new technologies such as antennae for microwave data transmission or the adaptation of new synchronisation protocols such as the White Rabbit project, which allows for improved accuracy and precision within and between places where transactions are executed.

The consequences of this technological race that rewards those capable of speculating the fastest reach beyond the financial sector itself. The sociologist Max Haiven (Cultures of financialization: Fictitious capital in popular culture and everyday life. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) explains how measures, ideas, metaphors, narratives and values typical of the world of finance transform other areas of society such as the management of public affairs, education and interpersonal relations. Financial speculation involves managing uncertainty within a logic where the greater the risk, the greater the potential profit.

In the current context of growing uncertainty and scarcity of time, space and resources, the logic of finance is seeping into the cultural fabric, making speculation, as an instrumental way of approaching the future, a generalised mode of managing the social experience of time. The chronopolitics of urgent issues (for example, in the dwindling time to mitigate even more catastrophic consequences of climate change) is combined with financial-computational chronopolitics in the management of economic affairs.

At this intersection, strange machinic interferences appear. As the philosopher Amy Ireland (Filosofía-ficción. Holobionte, 2020) explains, computational time operates on an alien time scale that overwhelms our ability for interpretation. To give an example, virtual assistants have to extend their response time to make their interaction seem more human. In this regard, Ireland notes, any event lasting less than a tenth of a second becomes invisible. Which means we are forced to develop machines to understand the temporal coordinates followed by the machines we make. By adding another mediating agent between the world we have made and the world that existed previously, we have moved further away from the sovereign capacity to manage human temporality.

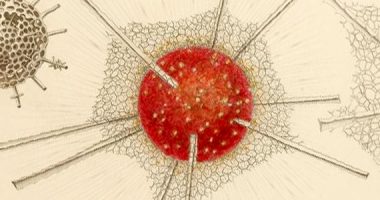

Watch repair shop., 1942 | US National Archives | Public domain

Designing chronodiversity

Modern chronopolitics (rational, instrumental, linear, causal and increasingly accelerated) has spread across the planet at the same time as logistics and information networks. More recently, these same infrastructures have spread the culture of financialisation and the ideology of innovation of Silicon Valley. These perspectives, materialised in very specific forms of technology but presented as universal, reproduce the visions of an elite that has managed to colonise an enormous part of the chronological, productive and affective organisation of global society.

Voices such as that of philosopher Yuk Hui (Fragmentar el futuro: ensayos sobre tecnodiversidad. Caja Negra, 2020) call for the incorporation of cultural diversity into technological development in order to prevent the futures produced by our machines from moving towards the homogenisation we are currently seeing. Similarly, decolonial thought defends not only the right, but also the need to recognise the value of other worldviews (which implicitly bring with them other types of chronopolitics) in order to face the Anthropocene. In a similar vein, and from the perspective of ecological economics, the theory of degrowth defends the need for other economic standards (more than just GDP, for example) that allow other productive activities to be visibilised. Recognising the immense complexity of the systems of which we form part, degrowth seeks to make room for the emergence of other paces that will lead to other forms of coming together. At the heart of this argument is a call for a slower and more attentive chronopolitics.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the writer Oscar Wilde and the economist John Maynard Keynes assumed that automation would free up working time. In this chronopolitical dream, they saw machines as a gateway, one which, however, has taken us to a place of quite opposite characteristics. Technical and intellectual objects, whether telephone wires, time standards, microwave antennas or economic indicators, (re)produce worlds and open portals to other dimensions. And yet, to echo Wajcman, the culture of immediacy does not allow us to generate new imaginaries around what it means to live well.

To design things or ways of doing and understanding is also to design ways of representing and experiencing time. These things often work like White Rabbits, entities that take us to other places that operate according to different rules. At a point when time seems to be running out, chronopolitics opens a useful entry (or escape) route for understanding how our sociotechnical organisation has made the world we live in. In a more propositional sense, thinking about a chronodiverse design might help us to resist the obsessive and hurried homogenisation of time by corporate technologies and experiment with other paces that open up other ways of living and being.

Leave a comment