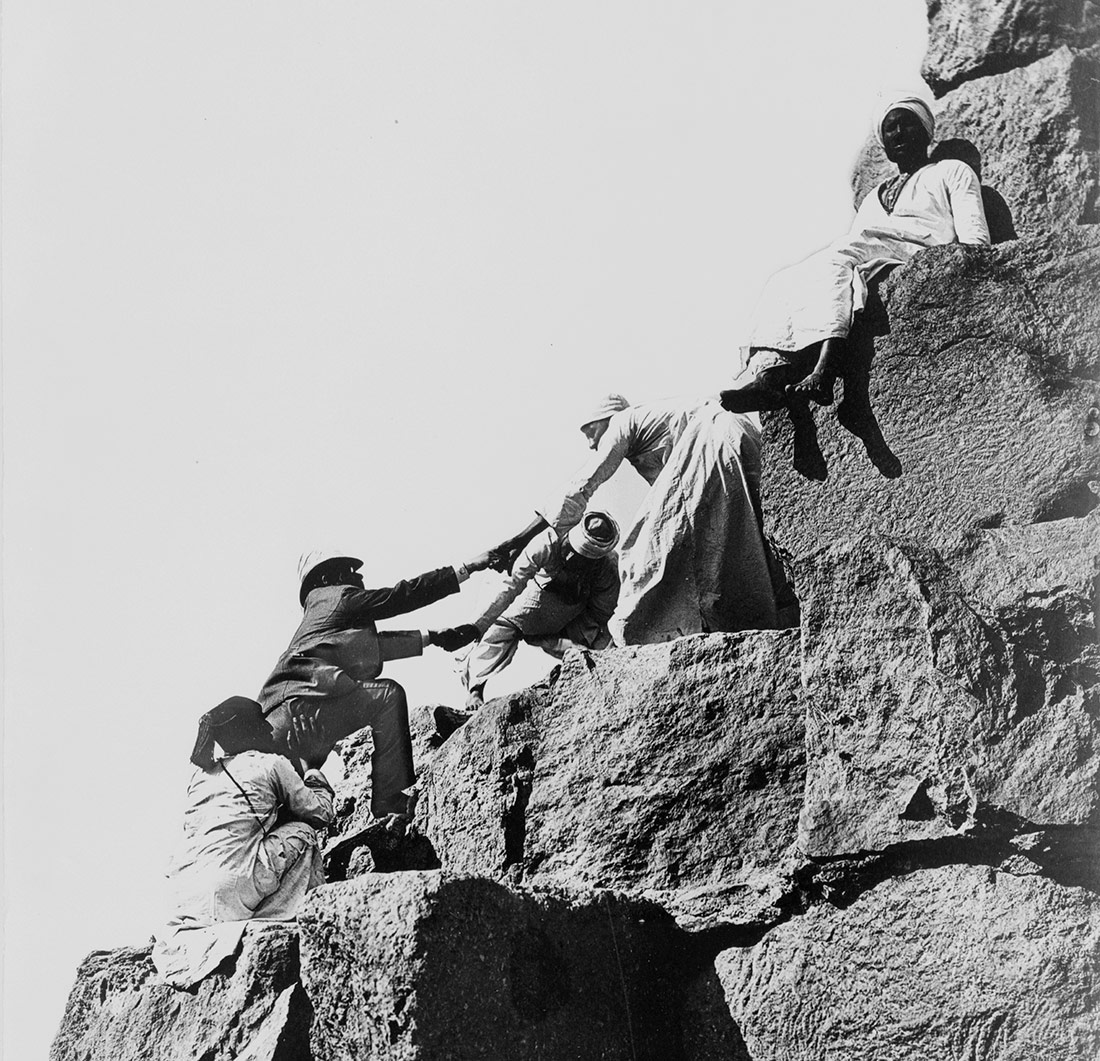

Tourist being helped up the great pyramid by Egyptian men. Egypt, 1870-1880 | Félix Bonfils, Library of Congress | Public Domain

COP26 could be a decisive summit. It is being held at a moment when the social debate around the climate crisis has gained new momentum and on the tail of a particularly dire report by the scientific community. As such, Glasgow could mark the turning point between continuing to take on theoretical commitments or bravely tackling the crisis.

The jargon of climate summits is undoubtedly complicated. We have had years and years of busy meetings, declarations of good intent, photographs of handshakes and triumphant hugs. As well as long faces, grimaces of disappointment and tragic appeals for immediate action. And now, all of a sudden, we find ourselves standing right on the edge of a cliff, our legs still wobbling after several months of pandemic vertigo. In Glasgow, at the 26th of those summits organised by the UN to reach agreements in the fight against climate change (the famous “COPs”), the international community is risking its credibility and – more worryingly – our future. Why is it so important?

Firstly, Glasgow comes with the inertia of the social debate about our relationship with nature and the overlapping of the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. It is also reviving – at least in part – the spirit of public mobilisation that swept the world in 2018 and 2019, spearheaded by Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion. Let’s look back for a moment to those months preceding the pandemic. The summit that was held in Madrid – and we must not forget that it should have been held in Chile – had a special significance. Never before had climate demonstrations been so massive; in some cities, in just a couple of years, they had grown from gatherings of a few hundred people to marches of tens or even hundreds of thousands. “Climate was in the air”, as the song goes. Madrid was therefore the bridge between the famous Paris summit, where a fundamental agreement was reached in 2015, and the Glasgow conference (originally scheduled for 2020), where the tools planned for Paris were to be developed and the post- Kyoto path was to begin. However, no relevant agreement was reached in Madrid and the feeling was, this time too, one of failure. Yet again. Either the next summit in Glasgow will be capable of taking up the spirit of the public movements and forging them into a legal framework, setting out the necessary tools and establishing binding agreements, or social protests will have yet another reason to turn towards rage and despair.

Secondly, the Glasgow summit is taking place after publication of the first part of the sixth IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report. The scientific evidence on the reality of global warming has been extraordinarily solid for years (just look at the headlines from 2014, 2007 and 2001, when the previous reports were produced) and the scientific consensus is overwhelming (99.9%), although this time the tone of the panel of experts has become particularly serious. Temperatures have risen by more than one degree since pre-industrial times, and we are well outside the safe level of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (around 350 parts per million, whereas we are now at 413). Moreover, the concentration of greenhouse gases continues to rise, even after the pandemic, wiping out the hope – harboured by many, albeit without any basis – that paralysing the world economy for a few weeks would serve to significantly slow the speed of the environmental crisis. The crisis is systemic and COVID-19 has produced short-term disruptions. Emissions of the gases that cause climate change fell by 18% in Spain during 2020 – a significant drop, it is true. But at the same time, this is very worrying, because, as this was a year when the country was locked down for months, it means there were 82% of structural emissions that do not depend on whether we take a plane, go out for a beer or drive to work. Individual actions always add up, but the degree of transformation needed can only be achieved through collective changes. And we must highlight the obvious – staying at home is not the way to fight climate change. The pandemic has caused and is still causing enormous pain to millions of people, and it is a health tragedy, but also a social and economic one. Turning it into a climate roadmap would mean making a bet on failure and suffering.

Thirdly and lastly, the very essence of the climate summits will be decided in Glasgow. In theory, their purpose is simple: to limit greenhouse gas emissions. However, if we look at the evolution and concentration of greenhouse gases over the last 30 years and superimpose the dates of the summits, it is clear that after each UN meeting and resolution, concentrations have risen again and again. Since the first COP, half of all greenhouse gas emissions in history have been emitted. The clear conclusion is that these “diploclimatic conferences” – as they were very rightly referred to by the former Valencian minister Elena Cebrián when explaining why she did not attend the COP24 in Katowice – the aim of which is to reduce emissions, have been hugely ineffective. With the current commitments derived from the Paris Agreement, which establishes a limit of 1.5°C temperature increase by 2100, we would reach almost double that – 2.7°C. Only one country is succeeding, in a recent international analysis in which the European Union, the USA, Norway, Canada and Japan, among others, failed: Gambia. What good are they then? Measures such as that staged by Extinction Rebellion on 25 October, when they blocked Madrid’s Grand Vía to demand decisive action on the climate crisis and at the same time that the Glasgow COP be the last one, are more than understandable. Why hold more if they don’t serve their original purpose?

Our civilisation is standing at a crossroads, one for which we have built an insufficient legal and institutional architecture that is frighteningly precarious in ethical and functional terms. The culture of climate “blablabla”, as Greta Thunberg decried, has taken over summits that have confused the instrument with the objective. It seems that the important thing is simply to continue holding them and applauding the meagre victories or agreements – only to fail to comply with them afterwards. And if it is so desperate, it is because a window of hope is open, because all is not lost. The same IPCC that tells us that many of the impacts we are seeing and that are to come (rising sea levels, heatwaves, changing rainfall patterns) are irreversible, also makes it crystal clear that it is still technically feasible to limit warming to 1.5°C and, in the worst case, to 2°C. That the decisions we make now and today, in this crucial decade, matter and will shape the rest of the 21st and 22nd centuries. At the very least. No human society has ever had this capacity to change the future, let alone consciously.

To make a habitable and humane future possible, we have to re-imagine ourselves, to stop living in a posthumous present, in the sense in which the philosopher Marina Garcés speaks of that time in which everything comes to an end. “We have been seeing the end of progress, and of the future as a time of promise, development and growth”, she affirms. We must shake off our fascination with the apocalypse, so present in contemporary popular culture (just take a look at the catalogues of current films and series). Faced with the self-imposed curse that we seem incapable of breaking and the mourning that we have been practicing in advance, we must defend the need to imagine different futures and, from there, to build them. Stopping climate change requires a root-and-branch transformation of a suicidal and cannibalistic system, but this is good news. Change will be hard, and yes, there will obviously be losers – those who benefit from the way the cogs of today’s world spin, accumulating wealth and exploiting countries, people and ecosystems. The world’s richest 1% consumes and emits more than the poorest half of humanity. For the rest of us, for the vast majority, the proposal is not to live worse in order to stop climate change; it is to convince ourselves that we must make the collective effort to stop climate change precisely in order to live better.

The Glasgow COP must choose which world it wants to belong to. Whether it wants to belong to a posthumous and fossilised reality that is brushing over commitments and promises with green paint or whether, on the contrary, it wants to stop asking the question of how long we can stand on an edifice that will collapse sooner or later and decide the direction in which we want to go. Whether we collectively decide that the 21st century has already begun – finally – and act accordingly, or whether we keep the 20th century on life support. If it were ever possible to unhook ourselves from the oil drip, now is the time. “Today is always still”, wrote Machado. Let’s fill today with meaning and hope, now that we still can.

Leave a comment