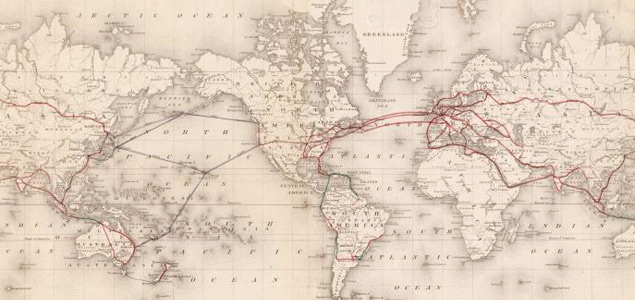

Main telegraph networks (1875). Soutce: Wikipedia.

The Internet is not an abstract entity that moves through the air. Rather, it is based on a mammoth physical infrastructure that spreads throughout the globe. The laying of the cables that make the Internet a global network raise geopolitical issues similar to those that are at stake in the case of oil pipelines. Securing a reliable source of connectivity has become as important as guaranteeing oil supply.

On 28 March 2013, the almost 3 million inhabitants of Armenia were cut off from the Internet for twelve hours. The digital blockade that the people of this country suffered on that day had nothing to do with the actions of an authoritarian government. Extreme weather conditions were not to blame either. The reason for the breakdown was much more outlandish than that. In a rural area of Georgia, 15 kilometres from the capital Tbilisi, a 75 year old woman with a handsaw single-handedly cut the cable that supplies Armenia with most of its broadband Internet. The pensioner assured the media that she was looking for firewood and had cut the cable by mistake. “I don’t even know what Internet is,” she told AFP after the accident.

This story was picked up by media outlets around the world, drawing attention to an aspect of the Internet that is often overlooked. Even though we are on the path to unstoppable digitalisation, there is still a widespread idea that the Internet travels through the air. Everybody knows that cars are made in factories, but many people still think of the Net as something intangible and without bounds. This is an erroneous notion that terms such as ‘the Cloud’ help to perpetuate.

In reality, the inner workings of the Internet include a very important physical component that can, in extreme cases, be affected by a grandmother cutting a wire in a neighbouring country. Just as oil travels from place to place by means of huge pipelines and cargo ships, data moves through optic fibre cables that wind their way around the world to take a YouTube video to your computer screen. You can display this video because it is stored in data centres full of servers that act as hard drives. These spaces have a considerable physical presence.

Google, for example, has 13 data centres including one at Hamina in Finland, at a former paper mill that was converted into a data centre in 2009. Google has already invested 350 million euros in the project, and plans to spend a further 450 million euros to expand it. To get an idea of the magnitude of the project, this construction work will make Google the biggest foreign investor in the Nordic country. These figures reflect the mammoth size of these centres that spread over tens of thousands of square metres. And Google is not alone. Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon have similar facilities scattered around the globe.

Visiting many of these data centres led journalist Andrew Blum to conclude that “each piece of the cloud was a real, specific place –an obvious reality that was only strange because of the instantaneity with which we constantly communicate with these places.” The writer spent several years on the physical trail of the Internet, an experience that he recounts in his book Tubes, in which spells it out clearly: “the networks of the Internet are as fixed in real, physical places as any railroad or telephone system ever was.”

The growing use of mobile phones to access the Internet can also be misleading: data transfer through the air only makes up a tiny part of the journey, between your device and the closest antenna, which is connected to the underground and submarine cables that carry data beneath the ground and the bottom of the seas and oceans.

“We take wires completely for granted. This is most unwise. People who use the Internet (or for that matter, who make long-distance phone calls) but who don’t know about wires are just like the millions of complacent motorists who pump gasoline into their cars without ever considering where it came from or how it found its way into the corner gas station,” wrote Neal Stephenson in an article entitled Mother Earth, Mother Board and published in Wired in 1996. This 42,000 word essay that now has cult status took the author around the world, on the trail of the 28,000 kilometre FLAG fibre-optic cable that began operating in 1999.

During his travels as a self-appointed “hacker tourist”, the intrepid gonzo journalist interviewed the daredevil engineers responsible for implementing this ambitious major global infrastructure project.

“The FLAG system, the mother of all wires, starts at Porthcurno (England) and proceeds to Estepona (Spain); through the Strait of Gibraltar to Palermo (Sicily); across the Mediterranean to Alexandria and Port Said (Egypt); down the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea, with a potential branching unit to Jedda; Saudi Arabia; around the Arabian Peninsula to Dubai, site of the FLAG Network Operations Center; across the Indian Ocean to Bombay; around the tip of India and across the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea to Ban Pak Bara, Thailand, with a branch down to Penang, Malaysia; overland across Thailand to Songkhla; up through the South China Sea to Lan Tao Island in Hong Kong; up the coast of China to a branch in the East China Sea where one fork goes to Shanghai and the other to Koje-do Island in Korea, and finally to two separate landings in Japan – Ninomiya and Miura, which are owned by rival carriers,” writes the American writer.

Like FLAG, hundreds of submarine cables are estimated to criss-cross different countries, creating an infrastructure that is vital for guaranteeing the operation of the Internet (in the USA, 95% of external communications use submarine cables). On top of this, an enormous number of cables operate without crossing borders.

Areas in which the water is less than 1000 metres deep pose the greatest difficulties when it comes to laying cables. Threats to the physical integrity of cables in these areas include ship anchors, shark bites, or being entangled in fishing nets at the bottom of the sea. Sabotage can also come into play, as it did in March this year when the Egyptian police arrested three scuba divers who cut the SEA-ME-WE 4 cable near Alexandria. Their actions slowed down the Internet connection for more than 24 hours in this Egyptian city and other areas that relied on the cable.

For these reasons, the preferred sites for landing cables are solitary tracts of land. “Cables almost never land in industrial zones, first because such areas are heavily travelled and frequently dredged, second because of pure geography. Industry likes rivers, which bring currents, which are bad for cables,” Stephenson explains.

On the corporate front, it is not unusual for telecommunication companies that compete with each other in different markets to from consortiums of a dozen companies to get a new cable going. This strategy lowers their costs and ensures the capacity required to supply the connection that their customers demand.

The geopolitics of Internet cables

As mentioned at the start of this article, the incident that left Armenia without an Internet connection drew attention to the vulnerability of the country’s infrastructure. If something as simple as a handsaw can destroy your network, you have a serious problem. In the more highly developed systems used in Europe and the United States, data have so many different ways of getting from A to B that in the case of an accident they are much more likely to find alternative paths to their destination. When we move away from Western territories and into more troubled zones, the configuration of the digital infrastructure becomes more complex, and also very interesting from the geopolitical point of view.

“Everything you read about geopolitics, about spheres of influence and national interests and so forth has a counterpoint on the Internet and how Internet structure plays out,” said James Cowie, CTO of Renesys, in a lecture at the Berkam Centre at Harvard University. To illustrate his point, the networks expert discussed the way the Internet is configured in the Middle East.

As Israel is surrounded by enemy countries, for example, its connection with the rest of the world depends on submarine cables that mainly go through Cyprus, Sicily and Greece to reach Europe and the United States. Palestinian territories, Cowie says, get their connection partly from Israel and partly from European operators that land in Jordan, which is in turn connected to the rest of the world by cables that pass through Saudi Arabia and the branch of the FLAG submarine cable that lands at the port of Aqaba.

Lebanon, which has no diplomatic relationship with Egypt, depended almost exclusively on a cable from Cyprus until 2011, when the I-ME-WE cable that begun operating in 2009 to connect France and India added a submarine branch from Alexandria to the coastal city of Tripoli. “They suddenly had a terabyte of capacity landing on their doorstep,” Cowie explained, which eventually took the pressure off an overloaded system.

In early November, the Internet connection was under threat because the Lebanese government owed money to the company that operates I-ME-WE. On 2 November the Finance and Telecommunications Minister issued a press release confirming that it had paid the 3.2 million dollar debt. The Minister also announced that if they were disconnected from the I-ME-WE network, the government had an alternative plan to use the Alexandros cable that had recently landed in the country. Securing a reliable connection has become as important as guaranteeing energy supply by using various sources to diversify the risk.

In the case of Turkey, its geographical position as a bridge between Asia and Europe is giving it the renewed importance that made it so influential in the Ottoman Empire. As Cowie says, “the fibre cable routes between Europe and Turkey flow down the old trade roads.” The country’s diplomatic strength is being backed up by investments from telecommunication companies such as Turk Tekekom and TurkCell, which are building new optic fibre cable routes towards Iraq, the Caucasus and Saudi Arabia. “They have realised that they are potentially a major exporter of Internet,” Cowie says, a way of increasing the country’s sphere of influence over its neighbours.

Above all, Cowie believes that geopolitical pragmatism prevails when it comes to planning the cable routes: “this has become a major strategic question: how to get the Internet cheaper, faster, and more secure without going through countries we don’t like.”

These same reasons led the promoters of FLAG to choose different routes in order to secure diversity, which, as Stephenson explained in his article, refers to “the principle that one should have multiple, redundant paths to make the system more robust.”

19th Century madmen

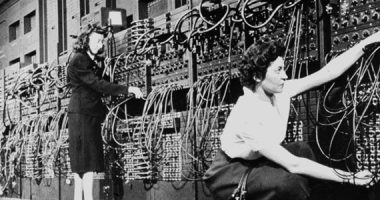

Access to high quality global communications would never have been possible without the work of the intrepid mid-19th century entrepreneurs who built the first submarine cables that cleared the way for the revolution of the telegram. “The only things that have changed since then are that the stakes have gotten smaller, the process more bureaucratised, and the personalities less interesting,” Stephenson says.

Back then, the margin of error was so great that only 5,000 out of the total of 17,500 kilometres that had been laid in 1861 worked. “The world has actually been wired together by digital communication systems for a century and a half. Nothing that has happened during that time compares in its impact to the first exchange of messages between Queen Victoria and President Buchanan in 1858,” Stephenson adds.

The path to the digitalisation of society will keep moving forward, but it will always be backed up by an infrastructure that is not only very real, but can be traced back to 19th century submarine cables.

The Eastern Telegraph Company network (1901). Source: A.B.C. Telegraphic Code 5th Edition, Atlantic-cable.

Domenico Fiormonte | 15 May 2016

Artículo muy interesante. Quizás habría que añadir una reflexión sobre la propriedad de los cables. Cómo ocurre en los bancos, en el “Big Pharma”, en la alimentación, etc. la concentración geopolítica y geolingüística de la propriedad es impresionante. Escribí algo al respecto en esta entrada: http://reartedix.hdplus.es/dixit/para-cuando-los-brics-del-conocimiento/

Leave a comment