Translated into more than 25 languages and renowned for the magnetism of her fantastic stories, Argentinean writer Samanta Schweblin explains how she created two of her most well-known works: Little Eyes and Fever Dream. She talks about writing during the pandemic and her passion for the short story as a device for distilling terror. She defends the Latin American women authors of her generation and writing workshops as ideal spaces to learn the craft of writing.

It’s not every day that a writer finds herself living in a story by one of her favourite authors. It happened to Samanta Schweblin (Buenos Aires, 1978) – one day she suddenly found herself transformed into a Shirley Jackson character.

The author, who has lived in Berlin for the last nine years, was caught out by the outbreak of the pandemic “in the south of southern Argentina”, where her family lives in a town of 2,000 inhabitants. “I went to visit my mother for a week and never came back. The government put a ban on moving between provinces and I was stuck there for four months. I rented a little wooden house, where there was nothing, a kind of ramshackle little cabin, so I could go and write. I remember one rainy evening, it was almost dark. It was evening, I was dressed in my mother’s clothes, with wellington boots, wild hair, the yerba mate gourd and thermos in my hand… I saw myself in the mirror and thought “who’s this woman?”

Like so many other writers, the project she was working on hit a wall, and the solution to get things moving again was to start writing a screenplay with the director Claudia Llosa, who lives in Barcelona, via zoom. The two of them connected from different time zones and, together, they got over the fixation with the pandemic. Their professional love affair actually started a few years ago, when they met to discuss the possibility of Llosa adapting Distancia de rescate (published in English as Fever Dream by Riverhead Books, 2017), Schweblin’s novel that offers a harrowing portrait of motherhood and fears.

“I don’t usually have a problem letting go of my texts,” explains the author. “They’ve already been adapted several times and I feel like the texts no longer belong to me when I finish them. But with Fever Dream I felt that there was something very personal and delicate. It was important that the narrative was very close to the reader on an emotional level. I had turned down several adaptations before Claudia came along. I sat down to have a coffee with her, and after ten minutes I thought: that’s it, I’ll give you everything, everything you want”. Between the two of them they wrote the script for a film that starred Dolores Fonzi and María Valverde and which was released on Netflix last September.

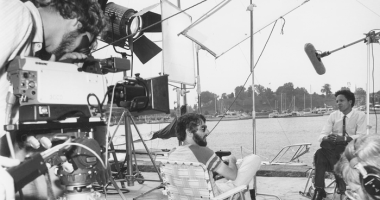

CC BY-NC-SA CCCB, Pau Fabregat, 2022

Fever Dream was also the story that took Schweblin away from her first love, the short story, and led her to the novel. But the Argentinean, who has published volumes of short stories such as Pájaros en la boca (published in English as Mouthful of Birds by Penguin Random House, 2019), Siete casas vacías (published by Páginas de Espuma, 2009), still considers herself a storyteller at heart. “I didn’t think: now I’m going to be a fully-fledged writer, I’m going to do serious things, I’m going to write a novel. What happened was that the text outgrew me. I sat down to write a 20-page story and at some point I realised I was on page 100,” she says. When someone recommends a new author to her, the first thing she does is read their stories. “I feel it’s the quickest and most effective way to get to know them. I wouldn’t say that the short story is better than the novel, but when a very powerful story manages to spin me around, to turn around something in my way of thinking, it blows me away. I love the economy, the effectiveness of the device. And I sometimes find it strange, seeing how obsessed we are about time, that it’s still a genre we read less”.

After Fever Dream, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, came Kentukis (translated into English as Little Eyes), a novel that could also be conceived as a collection of short stories. It’s a consolation for Samanta Schweblin’s father that this book has been translated into more than 20 languages, has comfortably installed his daughter on the front line of global fiction and is soon to become a miniseries, about which not much can be said yet. Because the first time Schweblin and her father talked about the seed of an idea for Little Eyes, he was disappointed. “When the idea emerged, it was so unusual,” Schweblin explains, “that I didn’t associate it with a literary idea. I met my father for lunch, told him the idea and he said: ‘This has to be patented immediately. Otherwise, the Chinese will make a fortune and we’ll be left without a penny’. I told him that I didn’t have the time or the inclination to patent anything, which is a very complex process, and my father, very disappointed, replied: ‘go on, write a novel’”.

The unusual idea, inspired by the trend for homemade drones in Buenos Aires at the time, is that there could be a stuffed toy with a mobile phone inside, managed by a human being, and that anyone could buy a kentuki or be a kentuki. Although the relationship between a human and their kentuki might resemble that of someone with their pet, the owner is in fact aware that somewhere in there is a human being, which brings up an array of questions as disturbing as they are tantalising in the mind of a novelist.

Anyone who labels Little Eyes as sci-fi or futuristic dystopia – as some have – is mistaken. After all, the technology that would make such creatures possible has been around for a long time. And the mental framework is the same as the one in which we all operate. “I’ve been wondering about this for some time,” admits the author, “we live in a hyper-technological world. I don’t find it surprising that I can send a voice message to my mother, who will receive it immediately 11,000 kilometres away. But the moment that same technology appears in a book, between two covers, then it’s high-tech, it’s futuristic. There’s a noise there that I find very interesting”.

Constructing such a choral and transnational novel – or series of stories, depending on how you look at it – with characters scattered all over the world and of different nationalities, solved another problem Schweblin was encountering: that of what happens to your language when you live far away from the place where you learnt to speak. The Argentinian inhabits what she calls a “Latin American bubble” in the German capital, a community of Mexican, Chilean, Guatemalan and Colombian speakers who soften their localisms to make themselves understood, while at the same time constantly borrowing and stealing the best picks from each dialectal variety. “Once you have ‘joder’, you can’t go back to ‘pucha’. They’re different things”.

There’s another, more informal bubble, to which Schweblin also feels she belongs – that of the Latin American women writers of her generation, people like Mariana Enríquez, Selva Amada, Fernanda Melchor, Valeria Luiselli and Brenda Navarro. Is there a group? “There is a group. We’re not all friends, we don’t all know each other. But we all read each other. There’s a lot of mutual admiration and there’s the joy of being at a party in full swing. Ten or fifteen years ago, literature written by women didn’t have this level of visibility. And I also think we all agree that the label ‘the new Latin American boom’ bothers us. The term ‘boom’ is unnecessary. Why should what the other half of the world is writing be a marketing tactic or a trend?” So there’s no boom, but there is a party.

Leave a comment