ARVE Error: src mismatch

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-aAJDQIJrF8

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/-aAJDQIJrF8?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=https://lab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/-aAJDQIJrF8Actual comparison

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-aAJDQIJrF8

src in: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/-aAJDQIJrF8?enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Flab.cccb.org

src gen: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/-aAJDQIJrF8

Colson Whitehead is in love with New York, the city where he was born and the setting for his latest novel, Harlem Shuffle. We talked to him about what lies hidden behind city streets and buildings, and about the memory and history of places.

All writers have their sacred places – their literary comfort zone, that world where they feel safe. In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, the best pages written by the American Annie Dillard come from observing the world from a cabin in the middle of the woods. For the English writer Philip Hoare, the key thing is to swim every day, and only from this contact with water can a text like Leviathan, or The Whale, be born. And for a beatnik like Jack Kerouac, this literary Ithaca was always the road – the thousand and one horizons that open up if you have a car with a full tank of gas. Then at the other end of the spectrum are the urban writers, those who always come back to the same setting – the city.

At first sight, the American writer Colson Whitehead would not appear to be one of these. His two most successful books to date, The Underground Railroad and The Nickel Boys, which made him the first novelist to win two consecutive Pulitzer Prizes, are both far-removed from the world of cities. The first is set in the Southern United States during the time of slavery, and traces the networks of help and solidarity that allowed thousands of African-American slaves to escape to the free states and Canada, while the other depicts the abuses suffered by African-American youths in reform schools during the years of the Jim Crow laws.

But if we stand back and look at Whitehead’s literary corpus as a whole, in other words, at all ten of the works he has published so far, then the city, and more specifically New York, emerges as the cartography, implicit or explicit, that is traced out by his stories. In The Intuitionist, his debut, two rival schools of elevator inspectors compete for the skyscrapers of an allegorical Gotham City. And in Zone One, his zombie thriller, the undead roam an apocalyptic Manhattan, “a utopia,” according to Whitehead, “because everyone’s dead and there’s no competition for taxis.” New York is also the city where the protagonist of The Nickel Boys finds refuge after leaving the reform school, and at the same time, the place left behind by the teenagers of Sag Harbor, perhaps his most autobiographical book, a coming-of-age novel set in this exclusive enclave of the Hamptons, the most sought-after second residence of the richest African Americans from the metropolis.

When you read Colson Whitehead, you know that he is likely to shift between literary genres from book to book, because today there are few writers more playful, versatile and experimental, but you can still be pretty sure that the setting won’t change too much. After all, Whitehead was born in New York, he grew up on the Upper West Side, he attended Trinity School, cut his teeth as a music and television critic at the Village Voice and currently lives in Brooklyn: “I’m a New Yorker, and even when I’m walking in Barcelona, which has very different architecture, or Madrid, there’s this energy that I recognise of people who may hate each other, but they’re stuck with each other. And sometimes that’s a city.”

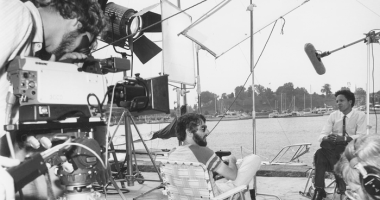

In Harlem Shuffle, his most recent novel, the roulette wheel of literary genres has stopped at the crime novel and heist movie, and the stories of Ray Carney, the crooked protagonist, are set in 1960s Harlem. Whitehead never saw the neighbourhood himself in the 60s – his parents were young adults at the time – but he has reconstructed it through a huge investigative effort: using books and newspapers of the time, but also mid-century furniture catalogues found on Pinterest and family Super-8s posted by local residents on YouTube.

Ray Carney considers himself a highly respectable furniture salesman, selling skai sofas and Formica kitchens to the growing African-American middle class, although his store stocks both new armchairs and stolen TVs, objects that, to put it another way, had a previous owner. In fact, from the nocturnal jaunts of Carney and company, populated by corrupt politicians, extortionists and murderers, a secret New York emerges, the criminal underworld that lurks behind so many seemingly normal restaurants and stationers’ shops that are fronts for brothels or illegal dens. “When I was younger, I would have a second shift of work. I might write from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., preparing the next day’s work and look out the window and there’s like one light on and the only people up at that hour are writers, criminals, alcoholics and insomniacs. So there’s this whole secret city that’s being built when everyone else is asleep.”

Harlem Shuffle also serves to confirm that a city is not just an agglomeration of people, streets and apartment blocks – it is also a way of seeing things, the way that each of us sees the world. When, for example, we look at the neighbourhood’s latest new gelateria and we don’t notice the queue of tourists lining up, rather we picture the heavy metal fan who ran the drug store that once stood there. “You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now,” writes Colson Whitehead at the beginning of The Colossus of New York, the homage to the city he wrote after September 11, 2001, and to this day he has retained this idea of cities overlapping in memory.

In Harlem Shuffle, for example, the story starts off on Radio Row, the district made up of three or four streets of radio and electronics stores on the Lower East Side that was wiped completely off the map when the Twin Towers were built. And when Carney walks along the streets, the reader knows that the World Trade Center won’t last either, and that there will be a new crater and new skyscrapers. “Being destroyed and then remade is part of New York. It’s also part of our personal experience,” explains Whitehead in the interview.

There is one last constant in the unclassifiable work of this literary chameleon: the commitment to speaking out against racism and the abuses suffered by the Black population of the United States. After all, Colson Whitehead is the most celebrated African-American writer since James Baldwin and Toni Morrison. He always tries to avoid being pigeonholed like this – something that he constantly has to mention during his travels in Europe, because “the whiter the country, the stranger the questions,” especially when journalist after journalist asks him about Barack Obama, George Floyd and Black Lives Matter. “I’m not your Black explainer,” he says in these cases.

But directly or indirectly, all his books contain a deep, penetrating and continuous reading of Black history, one that can be central to the story, like in The Underground Railroad, or be playing in the background, like a police siren, distant but unmistakable. Harlem Shuffle recollects the Hotel Theresa and the Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work movement, and Ray Carney’s tribulations coincide with the 1964 riot, which forces him to hang a “Negro owned & operated” sign on the storefront to avoid having his windows smashed in. This and many other landmarks of the period, scars of past discrimination, turn a seemingly innocuous novel on the nature of crime into an almanac about the fight for civil rights in the Harlem of the time. Because, as Whitehead explained in Time magazine, even though he may be one of the most successful novelists of the day, “whenever I see a squad car pass me slowly, I wonder if this is the day that things take my life in a different direction.”

Leave a comment