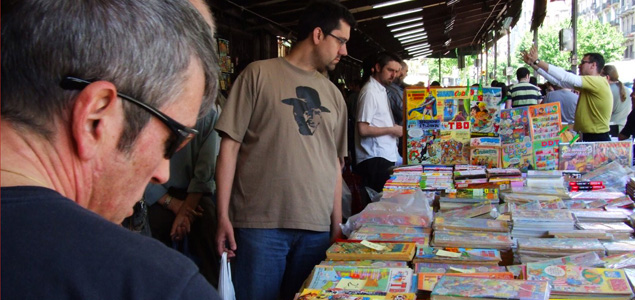

Sant Antoni Market, Barcelona. Photo: courtesy of Tristan Cardona, Blog La Canción de Tristán.

In recent years, media studies have taken a particular interest in the evolution of participatory culture: a culture in which spectators –the audience– leave behind their passive role and, as the term suggests, participate. Participating can entail giving an opinion or commenting, but also creating new scenarios or narratives, contributing new ideas (even without asking permission)… It all sounds very familiar and current to us today, but this is why scholars have thoroughly studied the phenomenon of fandom: communities of fantasy, science fiction, and popular culture fans, with a tradition that goes back eighty years… in the USA. But what is the situation in Spain, where the mass media and consumer culture developed under a dictatorship?

The heyday of Spanish fandom dates back to the sixties, as evidenced by the emergence of fanzines such as Dronte (1966, Luis Vigil), El fantástico (y científico) Torito Bravo (1966), Cuentatrás (1966, Carlos Buiza), and Anticipación (Luis Vigil and Domingo Santos, 1966), backed by Ferma publishing house. And also by the tentative associationism, the first fan conventions and events, and by the desire to create magazines and collections produced by fans, for fans, such as the mythical Nueva Dimensión (1968 Luis Vigil, Domingo Santos, et. al.).

Before then, science fiction and fantasy enthusiasts could only access collections such as Nebulae, published by Edhasa, radio plays like Diego Valor, and fantasy and science fiction comic books previously subjected to a good dose of censorship in order to ensure the moral rectitude of material destined to fall into the hands of young people (because in theory, until very recently, these genres were considered inappropriate for adults).

Vicenç Palomares concedes that fans of these genres either met by chance, or worked in related jobs (editors of collections, comic book illustrators, critics…), or, as others have said, met at bookshops or newsstands, always badgering for the same material. Later, in the seventies and eighties, fans would meet at places that redistributed second hand or remaindered material, such as Mercat de Sant Antoni in Barcelona and the Rastro in Madrid.

The social and economic situation in Spain was obviously a far cry from that of the true middle classes in the USA, which is the context that is always taken as a model when talking about the participatory culture of fandoms. The tentative, informal swapping of material was probably the most collaborative practice that existed before the sixties.

The decline of some science fiction collections by publishers such as Edhasa, the downturn in classic comic books or ‘tebeos’, the transformation of the dictatorship’s policy of economic development, and the conversion of the US Military Base at Terrejón de Ardoz into a kind of unofficial Madrid hub, where it was possible to obtain original superhero comics [1] that had not gone through the filter of censorship, for the dissemination of North American culture and subculture [2], (along with the negative aspects of the authoritarian regime) were the factors that probably sparked the generation of fandoms.

This means that in the early stages during the final years of Franco’s regime, the situation in Spain was different to the one that usually comes to mind when we think about fandoms, with a more tightly controlled popular culture.

Seizing the opportunity, a series of fanzines and magazines appeared in 1966, including Anticipación, which was backed by Ferma publishing house. In its fifth issue it clashed with the regime’s censorship and was forced to get rid of the readers’ letters section, which had started to become an element of cohesion for fans, and which had never before been included in a magazine (let alone catalogue) released by publishers.

Anticipación did not last beyond its seventh issue, but in 1967, its editors, Vigil and Santo, called for as many fans as possible to attend a meeting in Atocha (Madrid) to discuss the content and structure of what would become a legendary magazine by fans, for fans: Nueva Dimensión. The first issue came out in 1968, divided into two main sections: Mañana, for fiction, comics and poetry (Spanish and foreign, which they themselves translated with more care than other publications), and Hoy, for criticism and reviews, and, obviously, the crucial readers’ letters.

To launch the magazine, this time with permits, a small convention (Minicon) was organised in Madrid in January, a few days after a meeting held in Barcelona to present this first issue.

We obviously shouldn’t imagine an intense exchange of letters or fanart, because, as fans who remember this time always say, things moved at a different pace before the Internet, without this affecting the community spirit.

It is also significant that the Festival de Cinema Fantàstic de Sitges (also known as the 1st International Fantasy Film Week) was held for the first time in 1968, with Paul Naschy as a special guest, creating a new meeting point for fantasy fans who were drawn to film rather than literature. The fact that very little was known about these alternative film genres here seems to have been one of the main reasons that led to the creation of these events.

Nonetheless, the event that attracted large numbers of participants was the first Spanish Science Fiction Convention (which is generally known as Hispacón, and is still held today) in December 1969, with book launches (one by Edhasa) and round tables, an exhibition, a film session, and a play, Sodomáquina by Carlo Frabetti, in which some fans even volunteered as extras. And the police even interrupted it at one point for non-compliance. The third Convention in 1971 was held after the Sitges Festival, with the collaboration of the Union of Amateur Filmmakers.

When the first WorldCon was imported to Europe in 1970 (Heicon in Heidelberg), there was obviously a boom in these types of fan conventions all over Europe. It was a model that hadn’t existed before (there had only been salons organised by publishing houses until then), and groups of Spanish fans would get together to go to them and swap information, fanzines, and experiences with other fans from other places.

So there were highs and lows during these years, with small instances of censorship in between. For example, when Nueva Dimensión attempted to publish the satirical story Gu Ta Gutarrak by Argentinean writer Magdalena Mouján Otaño in 1970 the government to seize the magazine. But in spite of this, a powerful invigoration process had begun, with more actions and desires in favour of its development than against. They became the breeding ground for many more initiatives that gave rise to the emergence of new writers, illustrators and publishers, and a benchmark for the generations that followed.

If we ask fans who lived in Spain in the pre-Internet era about how fandom has changed in Catalonia and Spain, they admit that things are easier today, particularly when it comes to obtaining material. For example, fantasy and science fiction are so widely accepted nowadays that there is a huge range of series, films, comic books, video games and high quality fanart. And we can order a second hand out-of-print book through an online trading platform from someone on the other side of the planet. Some fans even think there is too much information or to much merchandising, and that this has watered down the spirit of associationism to some extent, or that it has been ‘replaced’ by Facebook groups and ephemeral tweets that are shared when a series begins on TV, so that the connections among participants are weaker, more relaxed, sporadic and circumstantial.

Cosplayers during the presentation of “Dance with Dragons” with George RR Martin at CCCB. Photo: Gloria Solsona, 2012.

This story shows us that a particular social and cultural context can either favour or restrict and slow down the creation of participatory communities. Technical media are important, and people end up using the simplest and most accessible ones at any time. But the legal and administrative framework that allows interactions and co-creations is also important. And it is also true that the scarcity of cultural material (including blatantly censured material, as in the case of some Marvel comics) can help to boost collaboration among fans eager to gain access to the yearned-for cultural products.

But above all, a lode of culture that is genuinely thought provoking, one that stirs up social feeling, that appeals to adventure and curiosity, that strikes a chord and raises questions about the uncertainty of the future or about the human capacity to resolve conflicts, and that occasionally also inspires human values – as well as some resistance or opposition, or sometimes a even a certain attack against itself– is what generates the strong involvement and commitment of a community of human beings. Neither technologies nor any other factor do it, at best they help to enable it.

[1] As told to me by the comic book illustrator and writer Cels Piñol.

[2] Orihuela, A. Poesía, pop y contracultura en España. Ed. Berenice:2013. p. 171.

Leave a comment