Open-air art class in the grounds of the school at Penygroes, Carmarthenshire, Wales 1940 | Ministry of Information – Imperial War Museum | Public Domain

The fact of climate change is beyond serious dispute, but has yet to become part of mainstream discourse in the UK or indeed beyond. Arts and climate science collaboration can help change this. In this article Lucy Wood, director of Cape Farewell and part of the jury for the 2nd Cultural Innovation International Prize, speaks about social commitment to the environment, about art and science as spheres of knowledge that feed off each other and that allow artists and scientists to increase citizen awareness and participation in environmental issues.

Soaring mercury, sinking cities, mass extinctions. It is easy to catastrophise climate change: faced with the sheer enormity of the climate challenge, people can tend towards despair and nihilism. For others, its seeming distance (both chronologically and, for many of us in the global north in particular, geographically) can seduce us with the easy denial that it is someone else’s problem to fix.

The technology and resources to move towards a post-carbon society are essentially all there. What we lack is a broad, civic movement to get behind the urgency – and significant opportunities – of this transition. So rather than looking darkly into a dystopian future in which we are passive victims, it is vital to make climate change relevant in the here and now – the air we breathe, the food we eat, the way we travel. Human-scale things we have agency to change. We need to find new ways to narrate and envision a fairer, cleaner future in which we can actively participate.

This year’s annual Lovelock Commission Cloud Crash by artist duo HeHe, a collaboration of Cape Farewell, the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) in Manchester, is an example of how art can enable major public engagement in what former chief scientific advisor Sir David King posits as ‘the biggest challenge of all time’.

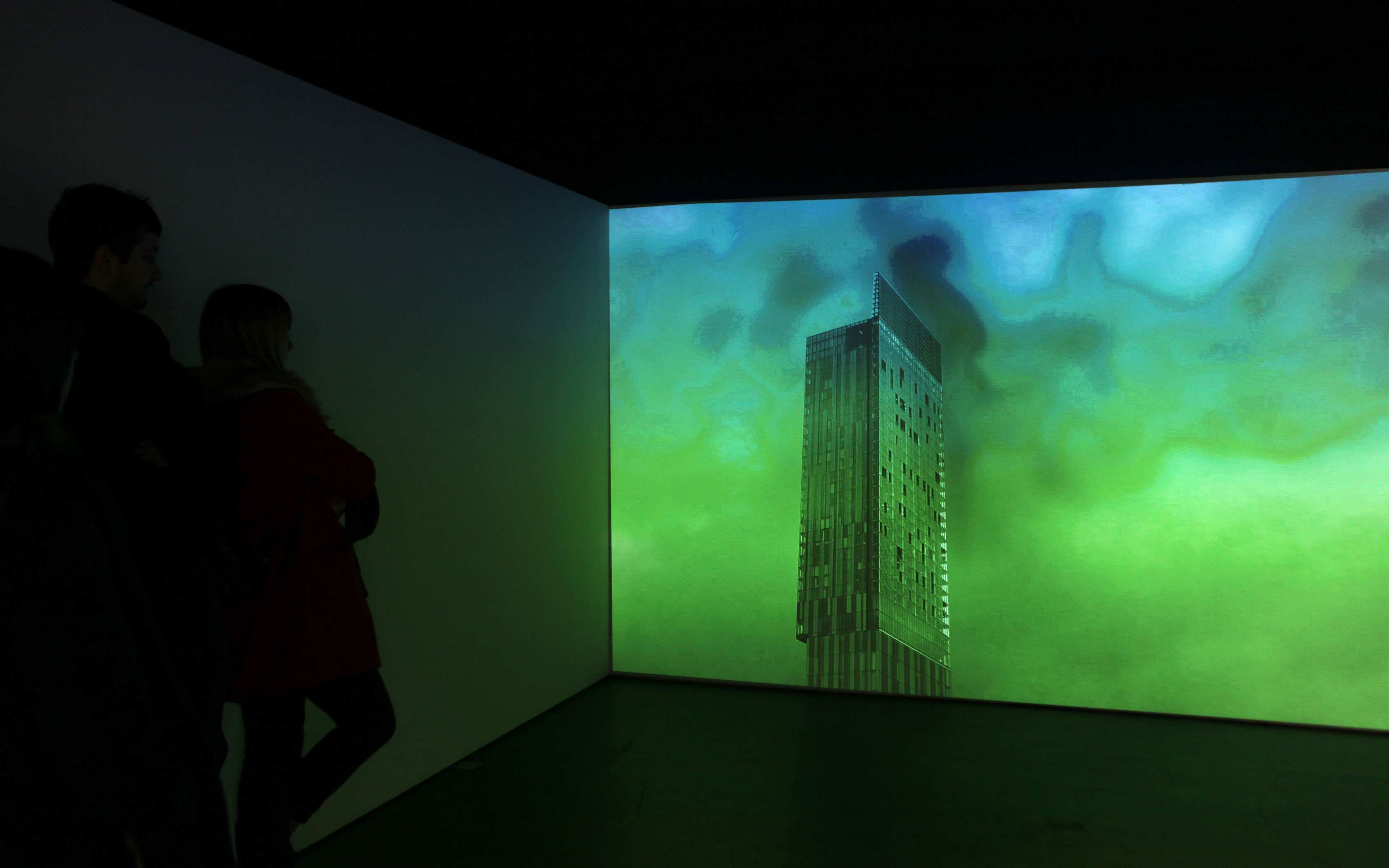

Diamonds in the Sky by HeHe | © Jason Lock

The Lovelock Commission takes inspiration from pioneering climate scientist James Lovelock’s Gaia Theory, which posits the earth as a single self-regulating organism – and this year the commission focuses on atmospherics – namely, man-made emissions. The headline event for this year’s Manchester Science Festival, Cloud Crash seeks to make pollution – and its component part, climate change – visible, and asks some uncomfortable questions of society.

The role of the scientist and that of the artist is to make the invisible visible. Gone are the pea soupers that choked London 60 years ago. Today’s pollution is largely invisible to the naked eye – and all the more insidious for it. A recent study by King’s College London revealed that 9,500 Londoners die each year due to long-term exposure to air pollution, and that levels of pollution in major cities including London, Leeds and Birmingham will exceed legal limits until at least 2030. WHO estimate exposure to the particulate matter – small particulate matter of 10 microns or less in diameter (PM10)- caused 3 million premature deaths worldwide per year in 2012 through cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and cancers.

This invisible menace needs to brought into the light so that we can understand what we are fighting. With Cloud Crash HeHe took as point of departure the air quality forecast maps produced by the (NERC funded) National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS) – that show, in hauntingly beautiful detail, levels of ozone, particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide as it sweeps across the UK.

What they have produced are three new pieces placed in-situ across the MSI site. In Airbag an ordinary car has crashed against a steel post in the courtyard. In a playful reversal of the polluting emissions of everyday cars (one of the largest contributors to lethal nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter emissions), this car has become a suspended cloud chamber, insulating a floating microclimate from the outside world. It is an object of reflection and provocation – as HeHe explain ‘there is a certain irony in admiring the beauty of such a fragile atmosphere, held inside an object which is so violently transforming our own unprotected airspace.’

Airbag by HeHe | © Jason Lock

Diamonds in the Sky is an immersive audio-visual experience based in the Air and Space Hall, that imagines a swarming cloud of pollution particles slamming into the side of Beetham Tower – Manchester’s landmark skyscraper which has come to symbolise the post-industrial reinvention of the city. Expanding on pollution forecast maps, this video piece highlights invisible ozone, nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter using vivid saturation colour – each particle per million represented by a pixel.

Finally, Burnout asks difficult questions of the arts industry and its role in climate change. A scale-model of the Tate Modern belches out vapour clouds – as if it is simultaneously an art museum and an active energy producer. The building’s original incarnation was Bankside, London’s major fossil-fuel power station from 1952 to 1981, whereas today Tate Modern is often referred to as an ‘art powerhouse’. By so doing, Burnout confronts both the building’s past and the arts sector’s modern day collusion with the fossil industry. Despite a recent decision from Tate to drop BP sponsorship after 26 years, the sector is still overshadowed by certain partnerships. For instance, what many pressure groups such as BP or Not BP call the ‘controversial and ironic’ sponsorship of ‘Sunken Cities’ exhibition by BP (a show rebranded as ‘Sinking Cities – Flooding our World’ by Greenpeace in a publicity stunt back in May)

Above and beyond, Cloud Crash explores a key issue – that to consume and create culture of all kinds is also to consume energy, however it may be sanitized. Brilliant organisations such as Julie’s Bicycle are doing vital work in helping the arts sector reduce their own environmental impacts. Without this, even the most successful public engagement activity and artworks relating to climate change could prove something of a Phyrric victory.

Artists and scientists are natural collaborators, both are explorers and storytellers, seeking out new ways of understanding, communicating (and indeed, changing) the world around them. So when it comes to the dry (or simply terrifying) language of climate science, the marriage of the two can be particularly fruitful. Artists can respond to environmental data in work that provokes real engagement. By communicating these issues in lateral, innovative ways, by using humour and humanity, these sorts of works can reach us on a more animal, cellular, level – and therefore, hopefully, demand our response.

Burnout by HeHe | © Olivia Hemingway

It is important to remember that the dialogue between artists with scientists is two-way. The innate creativity of artists can also inform the work of scientists. NERC’s recent call for public engagement pilot activity celebrates this dialogue, as they seek to support new work that engages members of the UK public with relevant contemporary issues of environmental science whilst also building engagement capacity in the environmental science research community – in particular providing opportunities for early career researchers and PhD students to develop skills in they way they approach, and present, their own research. The arts can come to the service of sciences as much as the other way round.

When it comes to climate science it is all about finding the right language and tone for it – reframing it as an opportunity not sacrifice, making tangible the intangible and giving agency where once there is apathy. Above all, we need to make climate change relatable to us all – and in this there is a great deal more work to do. It is vital that climate-focused arts reach as wide and varied an audience as possible. Diversity is critically important in the climate battle, enabling the society-wide engagement it demands.

Cloud Crash runs across the MSI site from 20 October 2016 – 4 February 2017.

The text is an adapted version of the original text published in The Guardian on 28 October 2016 to coincide with the opening of the exhibition Cloud Crash.

Leave a comment