Archaeologists at work in Sigtuna town. Sweden, 1941 | Carl Gustaf Rosenberg, Swedish National Heritage Board | Public Domain

In order to properly understand contemporary media culture, we have to start with the material realities that go before: the history of the Earth, geological and mineral formations, and energy. When we realize this, we are faced with the profound social and environmental consequences of our networked lives. Not only do we need rare minerals to make our digital machines work, but outdated media technologies return to the Earth as the residue of digital culture, contributing layers of toxic waste that future archaeologists will work on. Courtesy of Caja Negra Editora, we publish a preview of A Geology of Media by Jussi Parikka.

We want to bring these various components together now: planned obsolescence, the material nature of information and electronic waste. Planned obsolescence was introduced as the logic of consumer technology cycles, which is embedded in a culture of material information technologies that in themselves should be increasingly understood through chemicals, toxic components and the residue they leave behind after their media function has been, so to speak, “consumed”. The realization that information technology is never ephemeral and therefore can never completely die has both ecological and media archaeological importance. As a material assemblage, information technology also has its duration that is not restricted to its human-centred use value: media cultural objects and information technology have an intimate connection with the soil, the air and nature as a concrete, temporal reality. Just as nature affords the building of information technology—how, for example, gutta-percha was an essential substance for insulating nineteenth-century telegraphic lines or how columbite tantalite is an essential mineral for a range of contemporary high-tech devices—, these devices return to nature.1

In short, information technology involves multiple ecologies that travel across political economy and natural ecology.2 This Guattarian take on media ecology is connected to an ecosophical stance: an awareness of overlapping ecologies feeding into interrelations between the social, mental, somatic, nonorganic and animal. Indeed, following Sean Cubitt’s lead, we argue that archaeologies of screen and information technology media should increasingly not look only at the past but also inside the screen to reveal a whole different take on future-oriented avant-garde:

The digital realm is an avant-garde to the extent that it is driven by perpetual innovation and perpetual destruction. The built-in obsolescence of digital culture, the endless trashing of last year’s model, the spendthrift throwing away of batteries and mobile phones and monitors and mice… and all the heavy metals, all the toxins, sent off to some god-forsaken Chinese recycling village… that is the digital avant-garde.3

Our proposed alternative archaeology of tinkering, remixing and collage starts not with Duchamp and others but with the opening up of the technological gadget, the screen and the system.

Media archaeological methods have carved out complex, overlapping, multiscalar temporalities of the human world in terms of media cultural histories, but in the midst of an ecological crisis a more thorough nonhuman view is needed. In this context, bending media archaeology into an artistic methodology can be seen as a way to tap into the ecosophical potential of such practices as circuit bending, hardware hacking, and other ways of reusing and reintroducing dead media into a new cycle of life for such objects. Assembled into new constructions, such materials and ideas become zombies that carry with them histories but are also reminders of the nonhuman temporalities involved in technical media. Technical media process and work at subphenomenological speeds and frequencies4 but also tap into the temporalities of nature—thousands, even millions, of years of nonlinear and nonhuman history.5

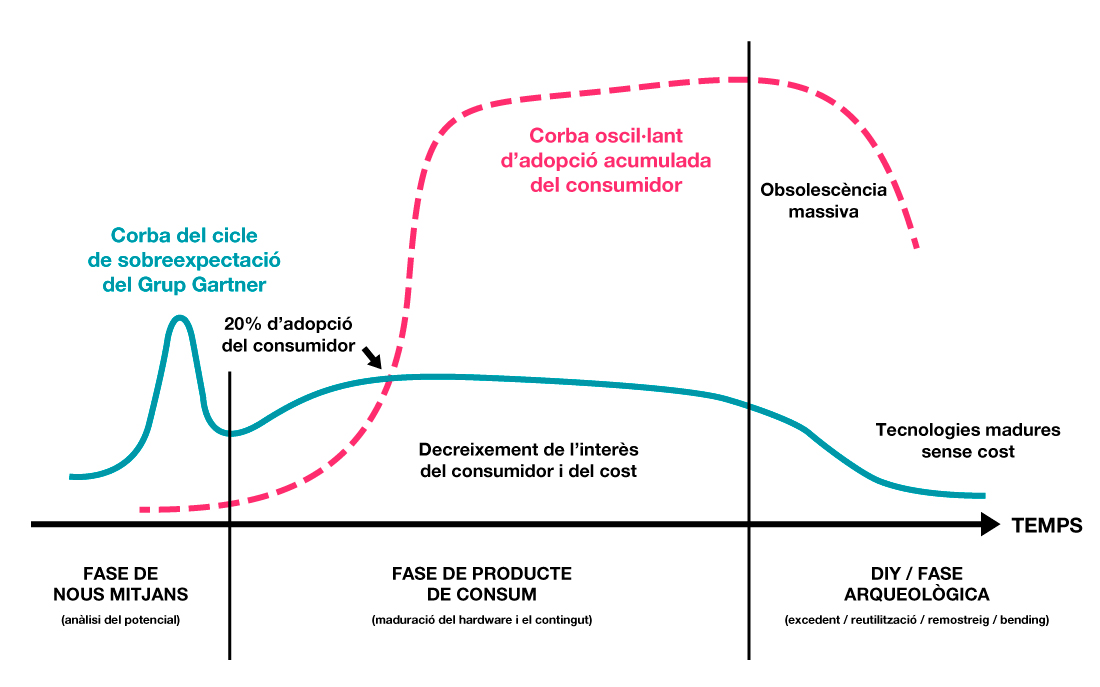

Phases of media positioned in reference to political economy: new media and media archaeology are overlaid on Gartner Group’s hype cycle and adoption curve diagrams, graphic representations of the economic maturity, adoption and business application of specific technologies. Diagram by Garnet Hertz.

In conclusion, communications have moved beyond the new media phase and through the consumer commodity phase, and much of it is already obsolete and in an “archaeology phase”. The practice of amateurism and hobbyist DIY characterizes not only early adoption of technologies but also the obsolescence phase. Chronologically, digital media have moved from a speculative opportunity in the 1990s to become widely adopted as a consumer commodity in the 2000s and have now become archaeological. As a result, studying topics like reuse, remixing and sampling has become more important than discussions of technical potentials. Furthermore, if temporality is increasingly circulated, modulated and stored in technical media devices—the diagrammatics and concrete circuits that tap into the microtemporality below the threshold of conscious human perception—we need to develop similar circuit bending, art and activist practices as an analytical and creative methodology: hence the turn to archives in a wider sense that also encompasses circuits, switches, chips and other high-tech processes. Such epistemo-archaeological tasks are not only of artistic interest but also tap into the ecosophical sphere in understanding and reinventing relations between the various ecologies across subjectivity, nature and technology.

Although death of media may be useful as a tactic to oppose dialogue that only focuses on the newness of media, we believe that media never die: they decay, rot, reform, remix and are historicized, reinterpreted and collected. They either stay as a residue in the soil and as toxic, living dead media or are reappropriated through methodologies of artistic tinkering.

[1] Gutta-percha is a natural latex rubber made from tropical trees native to Southeast Asia and northern Australasia. Columbite tantalite, or “coltan,” is a dull black metallic ore, primarily from the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, the export of which has been cited as helping to finance the present-day conflict in Congo.

[2] Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (London: Athlone Press, 2000).

[3] Sean Cubitt, interviewed by Simon Mills, Framed.

[4] Such hidden but completely real and material “epistemologies of everyday life” are investigated in a media archaeological vein by the Institute for Algorhythmics.

[5] Manuel DeLanda, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (New York: Zone Books, 1997).

Leave a comment