Woman writes a letter with pen and ink | Solveig Lund, Norsk Folkemuseum | Public Domain

It may seem like an outmoded hobby, but keeping a personal diary is a routine still practised by millions of people around the world, in a private notebook or in a blog for all to see. Beyond any literary value they may have, it is the historical value of diaries that has prompted various initiatives to preserve them. In fact, an entire industry has emerged around the preservation of family histories.

Since paper and notebooks were invented there have been diarists. Methodical writers, regular as clockwork, who wrote down their day-to-day lives, notebook after notebook, continuing doggedly through the centuries. Chroniclers who, as well as confessing and spilling their guts, immortalized the times in which they lived, in their notebooks preserving the world of yesterday for generations to come. First were the leaders of society—always men—politicians like Samuel Pepys or aristocrats like the Baron of Maldà, but with the spread of literacy anyone was able to explain the world—their world. There are millions of anonymous diarists today, and statistics say they are mostly women. Perhaps there’s even one in your family, because who’s never written a diary or had a diarist as a sister? Or kept a great-grandfather’s notebooks, or the letters their parents wrote when they were courting?

The routine of a diary-writer has been the same for centuries: buy a notebook, fill it up, buy another. Then, with the advent of typewriters, some diarists ventured into typing. And, with the Internet, some of these bold people created blogs, personal diaries on the Internet, for all to see. It was the first time diaries were shown to the world, instantly, allowing for comment and interaction, and many old-school diarists threw up their hands in horror. This display of what was previously private is called “extimacy”, a mixture of shamelessness and egocentrism, the fuel on which today’s social networks run.

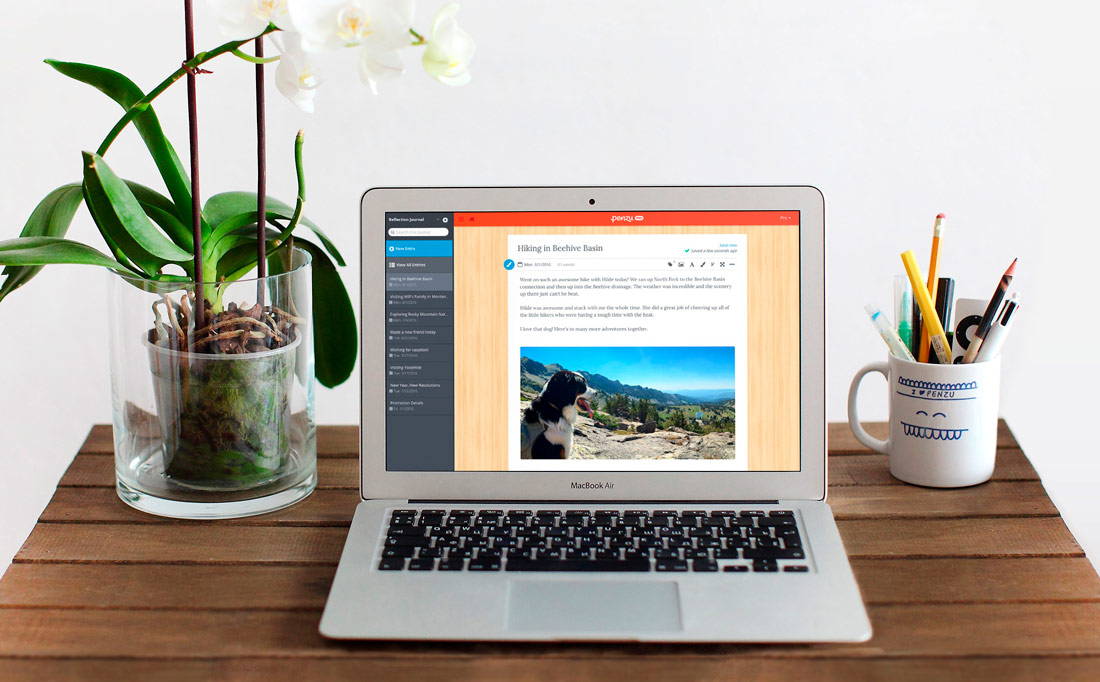

And personal blogs may have gone out of style, but the “to be or not to be” of 21st-century diary-writing—to publish or not to publish, filling notebooks kept under lock and key or websites open to the world, for all to see—continues. Stationers continue to sell diaries and notebooks for traditional diarists, but for those who no longer know how to write without a keyboard, new technologies offer a wide range of platforms. Those who want to share what they write now do so in communities of readers like LiveJournal, but there are also many private diary apps, such as Penzu and Diaro. And for those who find it harder to be methodical, 750 Words offers a gamified platform that urges you to write a minimum of 750 words a day.

Penzu is a private diary app

What shall we do with granddad’s diaries?

But writing diaries is a cinch. The problem with personal diaries is keeping them. Either because we’re ashamed of them, no longer recognising ourselves in those adolescent terms, decades later, or because we don’t know where to put them. Because it’s the law of life: with passing generations—and ever smaller flats—those letters, photograph albums and personal diaries we inherited from our great-grandfather just make the place untidy. And one day, sorting out, we decide to get rid of them. Flea markets are full of these testimonies of lives, and paper-recycling skips are often the destination of written lives.

To save personal diaries from the compost heap—or the bonfire—in the UK two diary devotees, Irving Finkel and Polly North, set up The Great Diary Project, a non-profit organization that accepts donations of diaries. You take them your grandfather’s notebooks that you don’t know where to put, and they look after indexing and keeping them. They’ve received more than 10,000 since 2007: there are schematic ones, like the 87 notebooks of diarist 225, a gentleman from Kent who, in a 1957 diary, wrote “heavy rain” on Tuesday and then spent Wednesday “gardening all day”, and there are also more detailed, sentimental ones, like the single volume bequeathed by diarist 224, which begins as follows: “1 January 1953 – What a marvellous start: a new name, a brand-new husband, a new house, a completely new life and even a new year!”

If I am able to share these excerpts it is because most of the treasures of the Great Diary Project are public and available for consultation at its headquarters at the Bishopsgate Institute in London. In the reading room you’ll find historians, academics and also novelists, because if you want to write a fiction set in post-war rural England, what better source of documentation than the diaries of a Lancashire farmer?

In Catalonia there is at least one similar initiative to save diaries, the Arxiu de la Memòria Popular in La Roca del Vallès. It was set up in 1998 at the initiative of Ernest Lluch and the then mayor of La Roca, now Minister of Health, Salvador Illa, and today has over 3,000 documents, mostly biographies and autobiographies, but also personal diaries and correspondence.

But all of these orphaned diaries may also end up in private hands. Around the world there are collectors who preserve thousands, bought at flea markets and itinerant fairs. EBay is another major source of diaries, and at auctions, old handwritten notebooks are sometimes sold for thousands of euros. Diary fever has even reached YouTube: US writer Joanna Borns, who talks on her channel about rarities she’s bought on the Internet, has thousands of views of the videos in which she talks about the personal diaries of strangers found on eBay.

Oral family histories, a growing industry

Familiar diaries: when you’ve got them, they just take up space, and when you haven’t got them, you wish you had. Because who wouldn’t pay to know more about their grandparents? To have a written record of their lives, notebooks or videos in which we could relive them, just for a few moments. Today, the preservation of family memories is an industry, but the world of oral histories on the Internet had a much more altruistic origin, dating back to 2003, with the creation of the non-profit organization StoryCorps. Since then, its team of interviewers has recorded over half a million personal stories, moving around the United States in their soundproofed trailers. They work with individuals, but also alongside museums or the Library of Congress of the United States to create thematic oral archives, such as the experiences of 11 September 2001 or the Stonewall Outloud collection of testimonies of the LGBTQ community. In Catalonia, since 2004 Sabem.com has been carrying out a similar task for the recovery of oral memory.

They are not diaries, but on the Internet there are numerous model questionnaires to find out the life stories of our relatives, with questions about their childhood and youth that can help us to reconstruct their biographies… as long as they’re willing to talk, that is. There are lots of companies that help create these family albums, with varying degrees of sophistication. StoryWorth send thematic weekly questionnaires to our relatives so that, over the months, they can tell their whole lives, and, at the end of the year, you have a memory book. Familiam offers similar albums in Catalan and Spanish, and platforms such as HeyArtifact and Saga go further, making a sound recording of the conversations so that our relatives’ lives are recorded in a kind of family podcast, little capsules in which the elders of the family tell their lives to future generations. The responsibility for preserving them, of course, is once again a question for our descendants, who, in the future, will have to decide whether to keep these testimonies, or consider them a nuisance as well.

Carmen Grau Sanchez | 14 January 2021

El meu pare, mort l’abril passat, va deixar escrita tota la seva vida de pagès en dietaris Miquel Rius.

Leave a comment