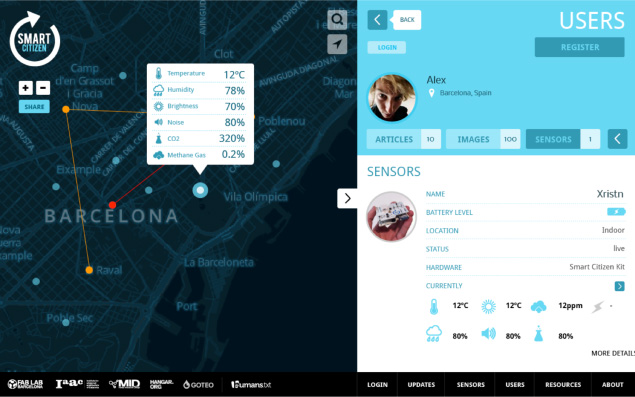

Smart Citizen Platform. Active citizens involved in the production of information and objects. A Fab Lab Barcelona project. Design: Leonardo Arrata for the Smart Citizen project.

The printing press, the oil industry, computers and the Internet are just some of the technologies that have radically changed our way of life at different points in human history. What will be the next great catalyst? What will take us a step further in our thirst to keep moving towards an unknown place or state? The recent information age has paved the way for the knowledge economy, and given us greater access than ever before to learning new digital and non-digital tools through the Internet and non-hierarchical communities. Communities such as Do It Yourself, Makers, Fabbers and Do-ers are revolutionising the way in which we produce technology, innovate and share new inventions: strange devices, objects and gadgets turn up every day on platforms such as Thingiverse, Instructables and Makezine, which allow anybody, anywhere in the world, to download the instructions, modify and adapt them, and produce them locally in Fab Labs, HackerSpaces and MakerSpaces. Mass media outlets specialising in technology are well aware of the enormous potential of this movement once it moves beyond the hobbyist stage and becomes a way of life, which means that ordinary people would even be able to use it as their primary means of livelihood – not just through financial exploitation, but as a way to meet basic needs, and to become part of a local community with a global influence.

Nonetheless, from the early twentieth century up until the present, our society has revolved around consumption, and our primary activity has been to generate money so that we can access goods and food processed thousands of kilometres away, so as to live and survive. This is so even though we could say that the period from the invention of the first computers and computer-controlled machines in the mid-twentieth century, up until the smartphone boom, has been the start of one of the most fascinating times in recent history. We now have unprecedented access to tools that return us to our roles as producers, particularly in the digital world: we upload images, we write articles in personal blogs, we denounce injustices on Twitter, we edit videos and post them on YouTube. And now, that same process of becoming producers is moving into the physical world, with the emergence of new tools for distributed fabrication –

tools that are made possible by the same computers that supposedly “disconnect” us from the “real” world in favour of the “virtual” world. These computers are connected to “digital” fabrication machines, which can turn digital models into physical objects in minutes or hours, and, as such, become an extremely powerful tool for changing our immediate reality in a human-centred way – as “prosumers” rather than consumers. Welcome to the world of the new digital artisans of our age.

Technology and humanity

In the fifteenth century, Gutenberg invented the printing press, at the same time as Europe was discovering a new continent: America. The conquest (domination of one over another) would not have been possible without the technological capacity that set the two cultures apart. But even so, the Europeans would not have been able to disseminate knowledge and religion in the faraway lands of the New World without the printing press. These were the years before the Renaissance, which was quickened by the capacity to reproduce and exchange information at a much faster rate than manuscripts, and by the potential to reach more places almost simultaneously. The medieval grand masters criticised the finishes of that new machine called the printing press, which deteriorated the art of handwriting with each reproduction. Every historical change requires a sacrifice, and every new invention calls into question an older practice, or makes a technology that had been valid up until then obsolete. The Renaissance paved the way for the steam engine revolution, the first industrial revolution ( Jeremy Rifkin, The Third Industrial Revolution) in the late seventeenth century. It radically changed the form of production in medieval cities, laying the groundwork for mass urbanisation and for the relocation of new poles of production that displaced the house-workshops in the centre of Medieval cities. Two hundred years later, at the turn of the twentieth century, the production model was reinvented once again with the so-called second industrial revolution ( Jeremy Rifkin), and the Ford T Model iconized standardisation or mass production. We made the shift from local industry to global industry, driven mainly by the military and technological world. In the early twentieth century, several interesting phenomena again coincided, such as the first wireless radio connection between America and Europe ( Guglielmo Marconi), which paved the way for television and new ways of disseminating knowledge and “culture”. In the same period, the birth of the Bauhaus led to the coupling of industry and design and the arts, while the discovery of oil opened up a new source of energy and by-products derived from its processing. Nonetheless, the phenomena that brought about the great technological change at the start of the century were of a more tragic kind: the First and Second World Wars.

The second half of the 20th Century

Far more than almost any other industry, the military industry accelerated innovation in the fields of telecommunications, materials technology, modes of production, food processing, the design of medicines, and much more, touching on almost every aspect that our lives depend on. In Sex, Bombs and Burgers, Peter Novak analyses how major inventions were the result of the military race during the two big wars of the twentieth century, but did not become truly transformative until they moved into the realm of private corporations, once the military conflicts were over. He also explains how the pornography and videogame industries optimised military technologies such as the Internet and home video, and how the fast food industry quickly developed new polymers for chemical compounds and packaging, in order to ensure the durability of food products and speed up production (although he notes that the first vacuum-packed food was consumed by Napoleon’s troops). Meanwhile, the ability to access food quickly has restructured the way humans live, by reducing the time we need to obtain and process food, which provides us with energy. This leaves us with much more free time for entertainment and recreation, and a whole industry was born to cater to it.

The world we currently live in is oil-dependent, industrial and wireless. Mass production has produced a particular way of thinking, of organising ourselves as a society, and a way of distributing resources in accordance with supply and demand, in a never-ending interplay between the dominion of one over the other, and of the maximum exploitation of the resources that provide us with raw materials, the energy that moves them, and the labour force that processes them. Nonetheless, in the mid-twentieth century new technologies emerged that fundamentally changed a world that had been functioning for a hundred years. Digital computing and communications became two of the most influential technologies in our lives: computers and the Internet. At around the same time last century, a production machine was connected to a computer for the first time, creating what would become known as CNC (computer numerical control) machines. Later, in the seventies and eighties, computers went mainstream, becoming smaller and personal, mainly due to the innovation that came out of garages in Palo Alto, California, although they would not have amounted to much if they hadn’t been taken up by big industries such as IBM and Hewlett Packard. These were followed by new companies such as Texas Instruments, Apple and Oracle, which became the driving force for the massification and advances of digital computing. Internet was Arpanet until the eighties, when it opened up and embraced the civilian world thanks to the philosophy of Vint Cerf and his colleagues who created a framework that could “talk” to the different operating systems that existed at the time and, above all, had the capacity to evolve over time. The Internet as we now know it has its roots in the military world, during the Cold War, when it guaranteed the connection between North American cities in the event of nuclear war. Each successive technology had a transformative effect when it became accessible. If we quote Buckminster Fuller: “It takes approximately fifty years before a technological invention becomes truly transformational”. It would appear that we are now at that moment of transcendence and transformation, when our technologies can definitively become agents of substantial change on a global scale.

Fabbers, makers, do-ers

In the late 1960s, Stewart Brand released the first issue of The Whole Earth Catalogue, a counterculture magazine that published articles with instructions for making solar ovens, analogue fabrication machines, low-cost radios, and many other “open” products to be shared with the local maker community. It became popular around the world and continued to be published until the late 1990s. The Catalogue was one of the most influential publications in the North American counterculture movement. It could be considered to be the start of the Do It Yourself (DIY) movement, and a source of inspiration for platforms such as MakeMagazine and Instructables, both of which document and publish open code projects and products. Instructables (recently acquired by Autodesk) allows people to download projects based on Arduino, instructions for building a 3D printer, and even food recipes. At the same time, users can also upload instructions for any project or product that they want to share with anybody that has Internet access. In medieval cities, the different guilds would share information using the means available at the time, building up knowledge and new practices together, in a dynamic that is not really so different from downloading a project from one of these new platforms in order to reproduce it or adapt it to a specific need, and at the same time offer feedback to the creator so that he or she can improve it.

Example of a page from The Whole Earth Catalogue.

Jeremy Rifkin uses the term “the third industrial revolution” to describe the current stage pf the transition that is taking place as a result of the profound financial crisis and the collapse of the planet’s natural resources. He believes that this transition will lead to the distributed production of food, energy and objects, which will be the key to developing a new, Internet-dependent model of human life on the planet. Meanwhile, Chris Anderson uses the term “the new industrial revolution” to refer to the “makers” movement all over the world, which disrupts the ways in which we produce, learn and innovate. Nonetheless, distributed fabrication will not replace industry as we know it; it will complement it, at least until we start using machines to build things, and until we learn what Neil Gershenfeld (creator of the Fab Labs concept) describes as the capacity to programme matter, given that matter contains code that can be reprogrammed in a way that is similar to the process by which ribosomes synthesise DNA proteins. In the meantime, computer-controlled machines, which layer, cut or drill materials, will accompany almost all aspects of our lives – from education, with projects such as the introduction of Fab Labs in schools and the United States Congress plan to establish 400 Fab Labs over the next few years, to food, medicine, and all areas of our lives. The main challenge is to change our role as consumers, in a world that has been created with this in mind for over a hundred years. We also need a new kind of literacy and a major overhaul of our current educational model, with a new focus on learning to learn. Education should also focus on new tools like 3D modelling and programming in different computer languages and codes, so that we can develop our own applications and programme our own microcontrollers in circuits that we have also designed ourselves. Just as photography, journalism and video editing have entered the domestic sphere and become affordable, disciplines such as mechanical and electronic engineering and 3D design will have to become part of the school curriculum over the next few years, so that they can be learnt (in new, more accessible ways) by anybody anywhere in the world. There are already many online learning resources that do not require a teacher or a classroom or a rigid timetable. Platforms such as Khan Academy, EdX, Fab Academy and Code Academy allow anybody with Internet access and certain prototyping and experimentation tools to take seminars in neuroscience, programming, circuit design, and the fight against poverty, to name a few, using educational materials from Harvard, MIT, Stanford, and a list of universities that is getting longer every day. Individual learning has great potential to develop new skills that aren’t offered in the traditional educational system, which is in need of a major overhaul. Nonetheless, learning as part of a community, alongside other people who are not necessarily teachers, also enhances education. It boosts the capacity for teamwork and develops empathy for others inside and outside the community. We need collaborative spaces, safe places where strange people with ideas can access production tools and where collaborative, open work is encouraged. DIY takes on a whole new dimension if, instead of Doing it Yourself, you Do It With Others (DIWO). There are already many open collaboration spaces of this kind: some are called Fab Labs, others are HackerSpaces or Maker Spaces. They operate differently in different parts of the world, but they all have something in common: they offer resources so that anybody can fabricate (almost) anything, without the need for advanced engineering or design knowledge. There are some 150 Fab Labs in over 35 countries around the world, and you can find at least one HackerSpace or MakerSpace in any major city on the planet today. These laboratories are open, collaborative spaces that don’t prioritise financial profit or academic excellence. Instead, they aim to resolve local problems with the available tools, drawing on an international knowledge network. How will the fact that anybody can fabricate anything, anywhere in the world, affect existing economic and production models? Can we imagine cities that fabricate whatever they need, within their boundaries? Will citizens be able to produce their own cities?

Sun lantern fabrication workshop. Fab Lab Lima.

Fab City

We live in consumer cities that are major importers of goods from factories around the world – televisions assembled in China, Korean washing machines, American canned goods and cars assembled in Eastern European cities. Millions of products like these are consumed in cities, they are used, they reach their use by date, go out of fashion, or wear out, and then they become junk or waste.

Cities are massive garbage-production centres, and human beings are the workers in these mega-factories of waste. We recycle less than a quarter of the waste we produce, and our consumption rate continues to rise. This model, which has been dubbed PITO – Product In, Trash Out ( Vicente Guallart, Antoni Vives, Neil Gershenfeld) – is the result of extreme industrialisation and standardisation, of offshoring production, separating it from consumers and at the same time removing production-related knowledge from cities. Cities are the quintessential spaces of human interaction, and also the infrastructures and means of production that allow this interaction to take place. Urban space today is not just squares, footpaths and parks, but also the Internet, and the two are becoming increasingly intertwined. It turns out that there is little truth to the apocalyptic doomsayers who predicted that the Internet and social networks would lead us to stay indoors and socialise only in chat rooms. Strangely enough, the opposite has turned out to be true: the Internet and other networks have become tools for greater and more efficient interaction with the city, our surroundings and our communities, using different media and applications created for this purpose.

The world of mobile applications is living proof that a different kind of innovation ecosystem is possible, that the traditional world of companies can often be surpassed by small networked groups that offer local solutions to global problems and vice versa. The exporting and copying of the “silicon valley” model has worked in certain environments and cities, while it has failed in others. But in any case, it seems to have run its course. We need a new model that is deeply committed to productivity and self-sufficiency in cities. A model that recovers the medieval spirit of local production, and is simultaneously connected to a global city knowledge network ( Vicente Guallart, La Ciudad Autosuficiente). Guallart, Vives and Gershenfeld call this model DIDO – Data In, Data Out – and put it forward as an alternative that would replace waste-producing cities with cities that produce goods locally, using internal energy and raw material cycles, and with high-speed knowledge sharing at a global scale.

In Barcelona, two new “Ateneus de Fabricació” (Fab Labs) are expected to open in 2013 – a brave, futurist project in the midst of crisis, with all the difficulties that this entails. The first two Barcelona Ateneus de Fabricació (the plan is to have at least one per district in the next few years), will be located in two quite different neighbourhoods. In Les Corts – an area with a high educational and social level –, the Lab (Ateneu) will be located at Les Corts Public Library. This is a futurist turn for local libraries, which swap their role as containers of the information stored in books and computers in favour of becoming spaces that provide the tools to change this information, from bits to atoms, through computer-controlled 3D printers, laser cutters, thermoformers and milling machines. Barcelona’s second Ateneu de Fabricació will be located at Sant Joan de la Creu Special Education School in Ciutat Meridiana. This is also a brave step in a neighbourhood that has a high rate of school dropouts and youth unemployment, but it is certain to provide opportunities for learning new professions and trades that are in line with our times rather than continuing with obsolete models.

Fab Lab Barcelona at IAAC.

The Barcelona Fab Lab network does not aspire to be fully City Council-funded. The idea is to have a mixed network of private, public and mixed initiatives that offer citizens new spaces for invention and innovation, and are part of a top-level global knowledge network. At present, the city has Fab Lab Barcelona, Europe’s first Fab Lab (other than Norway), which operates within the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC). The IAAC runs the Green Fab Lab as part of the Valldaura Self-Sufficient Labs projects, and aims to become a research hub on self-sufficiency in relation to energy, materials and food. There are also other initiatives run by organisations such as Makers of Barcelona (MOB), Betahaus, Hangar and other co-working and local production centres, which form part of a productive city ecosystem that is beginning to take shape. These, together with projects such as Consumo Colaborativo y Compartido, and open knowledge platforms such as the recently founded Open Knowledge Foundation Spain, offer the perfect ingredients for imagining a productive city on many different levels.

There can be no doubt that one of the key elements for cities of the future is the commitment to a model in which citizens are not just customers or consumer nodes, but active agents of change in the urban environment. Traditional urbanism has focused on physical space as the focus of city life, but, as we’ve seen, urban dynamics go beyond spatiality, aesthetics and design. They are also driven by internal production agents, and any attempt to think about cities without taking these agents into account would be an exercise in induced blindness. The technological changes that have taken place over the last few decades are taking us closer to a new definition of production in relation to the city. These changes go far beyond traditional citizen participation, redefining the operating model of the city, not just politically, but also in economic, social, cultural, environmental and geographic terms.

The productive citizen, or maker, or do-er, is much more than a hobbyist or “nerd” surrounded by machines, cables and computers, making odd inventions. The next challenge lies in setting up agreements at different levels between citizens, companies, governments and other agents that produce the city every day, and in generating shared or compatible visions with big doses of empathy and collective individuality.

Leave a comment