Lichen | Il·lustració de Martina Manyà | Tots els drets reservats.

Singer Maria Arnal put music to the words of the philosopher Donna Haraway and was joined by writers María Sánchez and Irene Solà, the three of them weaving a story of water that was presented in the framework of the Open City Biennial of Thought in Barcelona in October 2020 and is now published in the catalogue of the exhibition Science Friction. Life among Companion Species. It is presented here as an editorial preview.

All stories

begin in the water

All stories

begin with a word

All lives

begin with a cell

One 2nd September, María sent us an email in which she wrote:

Last night when I’d gone to bed, an image came into my head, quite suddenly: I thought about the little houses beneath the reservoirs, about the living organisms that also exist and make a house possible: insects, damp, lichen, the little plants born between the cracks and the rooftops would be among them… spiders, mice, lizards, geckos and cats, worms, moles in allotments, which nobody will have warned, cockroaches, ants and all their sounds, murmurings, moans, whispers what would this immersion in water be like? what would they transform into? how would water enter each of their cells?

There’s a story they tell in Rupit that says that all the animals (all the bugs) on the land, are replicated under the water. Sisters, but in aquatic form, in the sea and in the rivers. All the animals, except for the vixen, because she didn’t want to jump into the water. She was smart and didn’t want to get wet, and when all the other animals jumped into the sea, one after the other, the vixen suddenly vanished because she said there was too much juice in the sea.

This made me think of the image used by Alexander von Humboldt to explain the atmosphere. He described it as “an aerial ocean in which we are submerged.” It also reminded me of a text that fascinated me a few months ago, written by the researcher Astrida Neimanis, “Hydrofeminism: or, on becoming a Body of Water” in which she says: “We are all bodies of water… As watery, we experience ourselves less as isolated entities, and more as oceanic eddies: I am a singular, dynamic whorl dissolving in a complex, fluid circulation.” And she goes on to say “The space between our selves and our others is at once as distant as the primeval sea, yet also closer than our own skin – the traces of those same oceanic beginnings still cycling through us, pausing as this bodily thing we call “mine.”

Near where I grew up there’s a reservoir called the Pantà de Sau. There’s a village beneath it, and in the middle of the reservoir, you can nearly always see the top of the bell tower protruding above the water. Before you reach my village, you have to cross the reservoir. Go across it, skirt it, avoid it. Over the last few years, a tower, almost in ruins, has also been visible emerging from the water, reminding us that there, under the weight of the water, remain the traces of cells and beings that inhabited and were part of the village, before the water took over. It’s curious, my village heaves into view behind the reservoir a few kilometers away but it doesn’t draw water from it. Due to droughts, every summer for two years now the water has been cut off because the source has dried up. We can’t prepare our allotments; we can’t fill our water cistern. We think about our work and our herd. Our connection, our way of doing things. Last week, I felt cold in Galicia: fog, it was drizzling, and meanwhile my father told me there was already no water on the shore, that all that was left was a little pool, and that, at night, the wild boar go there to wallow in it and make the water muddy, and that, of course, the birds and newborn deer go down there to drink too, María. I picked up my hoe the following day, María,so that all the water would be together in one place and clean. I said to myself, so, this way they’ll be able to drink and look at themselves. They’ll look at themselves like I look at myself in a moist window pane and think of the distance measured by the drought, that churning in my stomach, how heavy my heart felt the day I saw a gum rock rose dry up for the first time.

I saw a rock rose dry up

dry dry, it dried up

if I could cry it a river

with my eyes, I cry

a truth that hurts, hurt

wells up green in my tear duct

a heavy churning, alas

a void left by

that rock rose rock rose rock rose

a rock rose

that no longer flowered

if I could cry it a river with my eyes,

I cry

There’s a Slovenian performer, Irena Z. Tomažin, who says that only the voice can truly expose our “inner core”. That bodies – and, as I understand it, our bodies, but all the other bodies, of entities, of things, of reservoirs, of primeval seas… – have a surface that marks the boundary where the eye stops. She says that the ear can hear depth. And that from the voice, by listening, from things that have been said, sung, imagined, we can submerge ourselves, sink, swim almost to the bottom, enter deep inside.

I don’t remember where I read an Indian story that said all natural things have a shadow or a spirit. Will the voice also reach them?

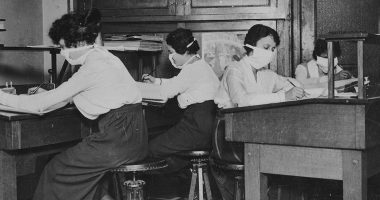

Silur | Il·lustració de Martina Manyà | Tots els drets reservats.

A few years ago, they tried to empty the Sau reservoir. To kill the wels catfish. And the place was teeming with people, with cars, with families who wanted to walk through the ghost village. To return home. To see their school. There’s a photo of a man going inside a cemetery niche. But they didn’t manage to get rid of the catfish and a man from Mollet said disappointedly to a journalist, “All that’s left are a few stones…”

All that’s left are a few stones…

All that’s left are a few stones…

Have you seen the pilgrimages that used to take place in some villages when the reservoir had run out of water?

The villagers went back to their houses, as if nothing had happened, opened the doors, looked around, took photographs of each other smiling, perhaps waiting for the next time it dried up. Perhaps they were replaced by the catfish. I say the words wels catfish and I feel a big, dark mouth that wants to swallow me and keep on swimming beneath the waters. Silurus glanis. An invasive species in this region. A banned species, an exotic species, a species that travels and colonises.

The river Ebro, which runs for 930 km and played a role in the founding of the Iberian Peninsula – it is said to take its name from the river – is full of wels catfish. The wels catfish originated in the great European rivers but how did the first one arrive in the river Ebro? When? Which current did it follow, as a freshwater fish? It happened in 1974, when an angler and ichthyologist crossed the Pyrenees with 32 Silurusglanis hatchlings from the Danube. More were introduced in 1995, from the river Po.

“This is Vicenç. He doesn’t say a word and runs his thick, rough finger across Ada’s ear. And he notices her pointed, metal earrings. And he thinks about the golden earrings in the shape of a bee that Ada left in the car the night before she left. He kept them in the glove box for a while, like a little treasure. And three weeks after Ada had left and hadn’t even written to him once, he parked the car at the viewing point over the Sau reservoir, went down to the water, and threw them in with all the strength his arms could muster, as far out as possible, into the middle of the reservoir.”

glug glug glug

what will the earrings sound like as they sink

what will a house sound like as it sinks

how will we hear, from under the water, the new forms that grow and inhabit a home

glug glug glug

the wels catfish likes low tones.

how will it hear them?

Do fish have vocal cords? Strange folds that emit a sound when they vibrate with the air and water. How do they do it? I read: auditory communication is very effective in water for physical reasons. Liquids, which are denser than air, favour a more rapid propagation of sound, at a speed of 1500 m/s compared with 340 m/s in the air. This means that cetaceans can communicate with one another across vast distances. Have you ever heard a whale sing?

“And these are Ada’s earrings in the shape of a bee, glittering and sinking beneath the water close to the submerged houses. And this is the huge catfish that ate them. And these are the earrings in the dark, stinking belly of the catfish. They had been there for years, waiting to be found.

And these are the three boys who caught it. The fish was so big and vicious and so heavy, that the three boys removed their T-shirts and had extricate it from the water by holding on to one another and pulling the fishing rod with all their might. When they had got it onto the bank, and they realised that it was the ugliest fish they had ever caught, one of them said:

“Now we have to kill it.”

I read that fishermen on the Danube use a type of wooden implement, called a clock,which, when it strikes the water, makes the sound of a frog, a bird or a tiny fish jumping over the water.

Will the moment before the death of the captive continue in a low tone?

Whales sing, bees buzz, owls hoot, horses neigh, goats bleat, cicadas chirp, storks clatter, ants stridulate, donkeys bray, but what about the wils catfish… ? I’ve had to look up all these verbs!!! How many verbs associated with the voice do we humans have? Why does a cicada just chirp and a donkey only bray? Doesn’t this lack of verbs mean we miss out on nuances and expressions and imply a radical lack of knowledge, or a profound lack of listening to the world?

We don’t have names but we do have the ability to listen. Perhaps on this side of the world, between buildings and concrete, we haven’t known how to appreciate the tones, the calls. I well remember the herd of goats I grew up with. They all had names. Living together, taking care of them, being sisters, you gradually learn to know when they’re happy, sad, when their bellies ache, when they get angry, when they are bored, when they jump and want to play, when they call for a kid that wasn’t born. I can still hear this voice filled with voices here, clinging on like lichen inside my skin.

“It was dark and summertime, and they were drinking beers and Fernet-Branca and coke. The tallest stuck a knife into the catfish’s slimy skull. The fish’s tiny eyes and long barbels didn’t move. Its skull was so thick and hard that the knife snapped off and blade was stuck inside the still-living animal. He grabbed another knife and stuck it into the fish over and over again. The bees could be heard chinking in its stomach. When it was dead, the tallest boy went to sit down some distance away, on his own, his hands besmeared with fish and death.

One of the others brought him a glass of Fernet.

“You did the right thing,” he told him. “We had to kill it. It’s illegal to catch them and put them back in the water. These fish aren’t a native species. The Germans brought them here and they’ve killed all the other fish, all the native ones.”

“You’re not a native either,” the tall one said.

The third one laughed in the distance at the fact that his friend was feeling sad about killing a fish the size of a shark. The second tried to stop himself from laughing too.

“Go ahead and laugh, you cowards, I was the one who had to kill it.”

I want to see photos of wils catfish in the water but Google only brings up dead bodies, catfish in the arms of beings posing proudly with their trophy. An invasive species, a banned species, an exotic species, a heavy species that eat one another.

They can live for more than 30 years. I’m now 31; I’d be a senile catfish, with my mouth shrinking, made wary by the clock and poachers.

Which little fish would you be?

The wils catfish is eaten in other countries. In Spain there was an attempt to sell it in tins it but it didn’t succeed due to the high quantities of mercury it contained.

“And they put the catfish in a plastic carrier bag and threw it in the rubbish and they never found Ada’s bee earrings. And who knows where they are now?”

xebriña xebra xebra xebra xebra!

They told me that if you said this spell in Galician, the animals that have gathered together separate off and each one returns home. There must be a ritual word for submerged species, for those that have learned to sleep holding onto the water, rooted in the mud and the trees that keep growing in spite of everything. For the absent ones, for the ones that have got wet, for the ones that are lost.

Imagine a page from an old photo album. Like the ones with yellowing lines from the glue where you used to stick the photos, which you then covered with a sheet of clear, thin plastic. There are six small black and white snapshots on the page, with captions typed in capital letters on bits of paper placed over the photos. UNCLE GREGORIO’S BALCONY 16.10.83. THE CHURCH VEGAMIAN MARUJA, RAMIRO AND ISIDORO 16.10.83. VEGAMIAN BRIDGE 16.10.83. VEGAMIAN BRIDGE 16.10.83. MARUJA AT HOME 16.10.83. ISIDORO INSIDE HIS HOUSE 16.10.83. There’s no glass left in Uncle Gregorio’s balcony windows but all the frames are there. I try to look at the photos as closely as possible to see Maruja, Ramiro and Isidoro’s faces, which are too blurred to show their expressions clearly. One thing that surprises me is that they look very small in all the snapshots: the houses are really big, with really high walls, the church looks enormous…I can’t stop picturing it all covered with water: so much water! I imagine what is going to happen after the photo taken on 16.10.83: Maruja and Isidoro holding hands, or does something have to happen? And if they don’t leave? And what if they decide to stay there, standing, counting the cracks and the new lichens that will come when the water rises again?

They do not swim.

I think of Isidoro and Maruja as if they were storybook characters. Somebody should write a story for Isidoro and Maruja. A story about Isidoro and Maruja. Or a song. But I wouldn’t want it to be a sad story. At least, not a sad story or song because their houses were filled with water and catfish as if they were fish tanks…

It would be lovely to write them a story, wouldn’t it?

Throwing breadcrumbs so that the catfish, the earrings in the shape of a bee and houses filled with bubbles and water would be left alone, so Isidoro and Maruja would have their own narrative, a different story, other than water and exile, where they would keep appearing in a photo but without reservoirs or expropriations. Where there is no longed-for return to their home because they never left.

Vegamian bridge.

Isidoro at home.

Maruja at home.

Isidoro inside.

I write this lichen

Lichen | Il·lustració de Martina Manyà | Tots els drets reservats.

Lichen, is an organism that arises from the symbiosis between a fungus (mycobiont) and an alga (phycobiont) or cyanobacteria. A third organism has also been detected in this union: a yeast from the Basidiomycota division, whose purpose is, as yet, unknown. Lichens grow in damp places, spreading over rocks or the bark of trees in the shape of leaves or grey, brown, yellow or reddish crusts.

I read this lichen, where you wrote the names in Catalan with the definite article, el Isidoro, la Maruja, and I smile remembering all my aunts from Barcelona who would go back to the village in summer as if they had never been away. My Auntie Carmen always used to say, Look at laMaría, how tall and pretty she is, she looks more and more like laCarmen (my mother) every day.

My Auntie Carmen died on a Monday in August, here in Barcelona. She couldn’t return home until the following Friday afternoon. We opened up her house and watered the yard at nightfall so people would think she hadn’t left us without saying goodbye. She died in a hospital, thinking she was in her village, near her kin, smelling the orange blossom in the yard in the evenings, hearing the voices of the neighbours as they peered into the hallway, the engine announcing the people returning from the fields at lunchtime. She had to die and leave the flower pots that are still waiting for her, and a story, like the story of so many I was too late for, the story of those who left, never to return.

And from nowhere, a stone comes into view. It appears to be lying flat, as if resting. The last water molecules from the Valdecañas dam are alone with it, accompanying it in its sleep, and around it, recently discovered moss, as if it were the moss that shaped this tiny stone animal, a boar. I smiled when I imagined the arms laying the stone animal on the ground, with care, singing it a lullaby, an omen, a sign, a way of warning us, of writing to us from the past, of someone who knows that the water would come one day and never return.

This stone has a twin in the Vall de Bianya. According to the legend, or, at least, to some people, when Hannibal crossed the Peninsula, with 90,000 soldiers, 12,000 horsemen,, 8,000 Iberian mercenaries nd 37 elephants, the Vall de Bianya was one of the many places he passed through. They say that a poor shepherd saw the 37 beasts and was so amazed that he carved an elephant into the rock. It can still be seen today, lying horizontally on the ground and covered in moss, at the top of the Puigsolana ridge.

Some people say the terrible earthquakes that happened in Olot in the 15th century knocked over the elephant stone. Others say that it was carved in this reclining position, pointing to the ground. Some people even say that the stone was carved in the 20th century by a shepherd or a shepherdess who had seen elephants on television. Quite frankly I don’t care who carved it; what I like are all the possibilities, the elephant stone as a seed for many stories.

Do you know the legend of the Coll del Pal?

An area of land that is said to be desolate but whose pastures have always been used by shepherds, so ¿por qué entonces esa desolación? Perhaps it comes from the legend of a hiker who wanted to climb up to the mountain pass, or collao, while the gathering fog became thicker, denser, obscuring the path, eagerly awaiting the wind and snow.

What was the exact sound of the first snowflake as it fell?

Would it bring respite to the hiker?

Up there some shepherds were checking on their animals, winter was drawing near, and how! and they, so far away, so far away from home

had to spend the night in the harbour

would there be a little hut, high mountain pasture or shelter?

Yes, there was hut, tiny and rickety, that let the rain in and the wind blow through.

inside, the firelight

outside, the crow

and its cawing time and time again

it warned with no ill omen,

– how unjust we have always been to them –

that a guest, the hiker, was getting near.

The firelight always warms,

and that evening it was the only thing that spoke.

Because there was no room for anyone else among the bodies of animals and other beings.

So he retraced his steps,

looking for a warm nook among the stones

that way, maybe he would hear the heartbeat of the moss

nestling under the snow.

But he couldn’t

his body couldn’t

his voice couldn’t

and the following day they covered him with pebbles and twigs.

They say that the sun always shines on his grave,

and that the shepherds never left the mountain pass

they stayed up there,

kindred brothers,

their voices and bodies transformed,

one by one, into tiny stones.

Final poem

insects, damp, lichen, the little plants born between the cracks and the rooftops would be among them… spiders, mice, lizards, geckos and cats, worms, moles in allotments, which nobody will have warned,,cockroaches, ants and all their sounds, murmurings, moans, whispers

Will the voice also reach them?

“I am a singular, dynamic whorl dissolving in a complex, fluid circulation”

that all that was left was a little pool, and that, at night, the wild boar go there to wallow in it and make the water muddy, and that, of course, the birds and newborn deer go down there to drink too, María. I picked up my hoe the following day, María, so that all the water would be together in one place and clean.

“All that’s left are a few stones…”

All that’s left are a few stones…

All that’s left are a few stones…

For the absent ones, for the ones that have got wet, for the ones that are lost.

UNCLE GREGORIO’S BALCONY. THE CHURCH VEGAMIAN MARUJA,

RAMIRO AND ISIDORO. VEGAMIAN BRIDGE. ISIDORO AT HOME.

MARUJA AT HOME. ISIDORO INSIDE HIS HOUSE.

I can’t stop picturing it all covered with water: so much Water!

I write this lichen

All stories

begin in the water

All stories

begin with a word

All lives

begin with a cell

END

* In the English translation, the interventions of each author are identified as follows: text in green by Maria Arnal, originally written in Catalan and Spanish; text in blue by Irene Solà, originally written in Catalan and Spanish; and text in black, by María Sánchez, originally written in Spanish.

Leave a comment