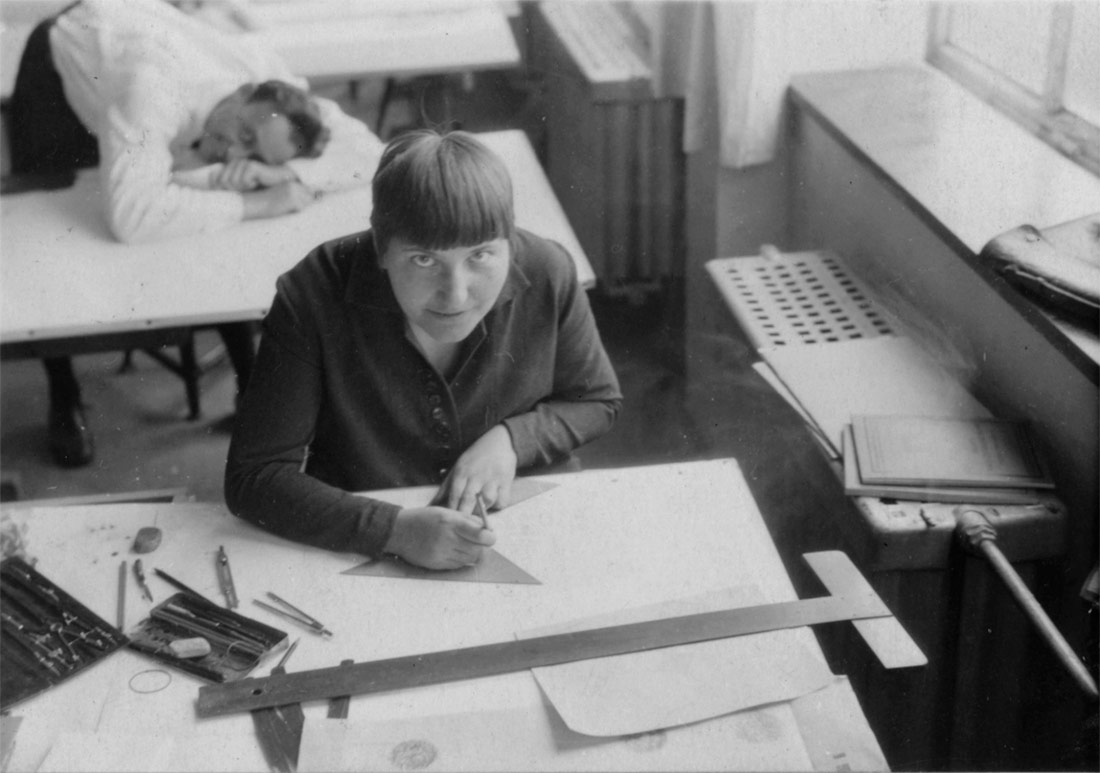

Life at Bauhaus Dessau: Students in the Department of Architecture. Lotte Beese and Helmut Schulze at the Tracing Table. c. 1928 | Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain

In an era in which references from the past are losing currency and authority, the legacy of the Bauhaus may well be an exception. Born at the dawn of mass production, considered one of the birthplaces of modernity, it was an institution called to break structures, in both the field of design and architecture and that of formal teaching.

On 1 April 1919, the town of Weimar witnessed the opening of the Staatliches Bauhaus, the art school that gave shape to design as a professional discipline. During its nearly fifteen years of life, in three different cities, its classrooms played host to teachers of the stature of Vassili Kandinski, Paul Klee and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The institution proposed to create forms that responded to the challenges of its era, that of a Germany deep in the depression between the wars and in the throes of full industrialisation. Inside its walls it trialled alternative ways of living, working and relating, until the Nazi authorities forced its closure in 1933, accusing it of promoting Bolshevism. Beyond its interest as a stylistic movement and feature of a nostalgic review of the 20th century, we find its mark one hundred years later in cultural practices typical of the digital era.

Leaning by doing

Architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, illustrated the school’s manifesto with a print of a building that was not at all modern: a cathedral. For centuries, churches had been built without tools or sophisticated scientific theories, thanks to people who trusted in practical experience and the craft tradition. That is why Gropius considered them the epitome of his view of art: a collective work, the union of all the trades in a single global project.

Although its orientation gradually mutated with the passing of time, the learning of trades was a cornerstone of the school’s teaching. The Bauhaus programme was developed in three phases: 1) An introductory semester with lessons on form and materials in general, 2) Three years of learning in a workshop and 3) An indeterminate period applying knowledge in constructions.

From its beginnings, workshops were established for ceramics, textiles, metal, glass and mural painting, among others. Only students who showed aptitudes could form part of the workshops, where they were under the charge of two teachers: a form teacher and a craft teacher. A dual teaching system – not free of tensions – that provided two mentors for each student artist, blurring the hierarchical figure of the traditional teacher and enriching works from an artistic and a functional viewpoint.

The majority of the teaching staff of the Bauhaus had never been trained to teach, therefore it was largely composed of working artists. This proposal broke with the traditional academy idea, in which only people who had taken examinations were fit to examine. For Gropius, the old institutions were incapable of training artists. “How can they achieve it, if art cannot be taught?”, he wrote. This heretic view of expert knowledge, together with that of learning through practice, eliminated to a large extent the hierarchies associated with the school as an organisation.

The artist, Johannes Itten, for example, let students themselves evaluate which works were best. In some workshops there were not sufficient resources nor any formal programme, so the people forming them had to find ways to take them forward. Evident proof of this was the textile workshop, to which the majority of female students were sent, as the work there was considered an inherently female labour. Students were self-taught, for which reason some of them, such as Gunta Stölzl, took courses on their own account. They would subsequently share what they had learned with the rest, making possible the progress of a workshop that otherwise would have disappeared.

Digital crafts

For a school to be multidisciplinary may seem to be quite common today, but back then it was an exceptional idea. Artists, craftspeople and designers were pushed to collaborate, find the balance between individual work and teamwork, art and technology, modern science and traditional knowledge.

This “hands-on” focus and collective learning are in tune with contemporary practices, which emerged at the heart of the digital revolution. For decades, different disciplines reformulated the patterns of the do-it-yourself philosophy, grouping together people with the same interests both face-to-face and online. A good example of this are the Fab Labs and the Maker movement, which establish digital fabrication centres where they design and print objects, often without the need for any expert knowledge. Many of them, furthermore, constitute authentic practice communities, in which the processes are shared openly and people learn from each other, recognising themselves as craftspeople, but of a modern-day technique.

In the same way, hacker and free software philosophies question who has the right to produce technology, advocating direct intervention in the creation of programmes and, therefore, of knowledge. Something that sociologist Richard Sennett has referred to as “public craft”. According to this United States author, free software is an example of how to construct useful tools for society based on collective work: “This community”, he writes, “is focused on achieving quality, on doing good work, which is the craftsman’s primordial mark of identity”. New ways of generating artefacts that are not marginal, but that have broad mechanisms of relation and communication, as well as the recognition of status and cultural capital. Systems that, for Sennett, are more sustainable than those of the closed structures in which everything is written and procedure and for that very reason do not know how to adapt and survive.

Moreover, the very idea of a Bauhaus workshop, halfway between learning and production, between work and play, has become omnipresent in the current educational field. The workshop, a format that encourages the application of what is learned in real time, permits teaching to adapt to what people need. Although its configuration, due to its ephemeral and anti-academic nature, can make it weak in some contexts, it is highlightable as a space in which capacities can be developed without the formal demands of the educational world nor the urgencies of the business sector.

People-centred design

Despite the fact that the modernity of the Bauhaus may seem, to today’s eyes, cold, minimalist, and somewhat elitist, one of the school’s fundamental pillars was the use of design for a social purpose. Following Germany’s defeat in the First World War, Walter Gropius advocated an art at the service of human needs. As the manifesto of the Council of Workers for Art, a collective in which the architect participated, said: “Art and people must form a unity. Art should no longer be the pleasure of a few, but should bring joy and sustenance to the masses”.

Bauhaus. Dessau, 2010 | Nate Robert | CC BY

Taking this principle, the Bauhaus placed emphasis on simplicity and utility, as much in the use of materials as in the form of the design. In opposition to the over-elaborate style of bourgeois modernism, the unnecessary ornaments were eliminated, under the premise that the form must follow the function. This postulate was also applied in the field of architecture, and the school revolutionised the way of planning buildings. Especially under the direction of Hannes Meyer, the living conditions of working-class families were studied, taking into account biological and psychological aspects, as well as environmental and urbanistic aspects. These often revealed “the deficiencies and classist character” of cities, as Meyer wrote, in which “the working-class neighbourhoods were, without exception, in areas deteriorated by industry and cultural facilities in areas where the wealthier population lived”.

The social focus which the school promulgated finds an echo in design thinking and other current methodologies for innovation, which highlight the value of the role of design in the resolution of problems. According to these disciplines, the priority always must be human needs, therefore it is not necessary to put the focus on the creation of objects in itself, but on their interaction with people, environments, cities, etc. A consideration that “requires unusual collaborative skills that many organizations have not yet developed” as written by Havard professors Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey F. Rayport; as well as profiles with different baggage interacting in a creative way. Qualities typical of the Bauhaus that these academics miss “because those who know what can be done are not generally in direct contact with those who need something to be done”.

Giving form to the present

At the dawn of an automation of employment that is predicted to be massive, it seems evident that digitalisation is putting an end to the capacity for making with one’s own hands, at least from a professional point of view. Recovering the ability to mould the world passes through the analogical route, but also through the need to acquire competencies typical of the current context. In the same way that it is important to preserve the capacity to weave, bind books or forge, it is necessary to teach how to programme, print and design, since this is unceasingly the way of working raw material that shapes the present.

An inspiring experience in this sense is that of the Fab Loom project, which links in a tangible way the analogical and digital craft traditions. It consists of the fabrication of a replicable loom designed at the Fab Lab of Lima, constructed thanks to a numerically-controlled milling machine and using as a source the ancestral Peruvian loom. One example of the possibilities of new forms of production for tackling the challenges of the near future in a different way, on both a local and a global level. An experiment carried out in a collaborative and multidisciplinary way, that shows that the approach of the Bauhaus still has a place in a world governed by binary code.

Leave a comment