A man and a woman watching a film footage of the Vietnam war on a television, 1968 | Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

The assassination of the Archduke of Austria in 1914 and the world war that it unleashed represented the beginning of the last century. However, it is difficult to establish the beginning of the 21st century from a single event. Although we think about the fall of the Twin Towers as the start date, its impact cannot be understood without the influence of the systems of representation that prevail in our society.

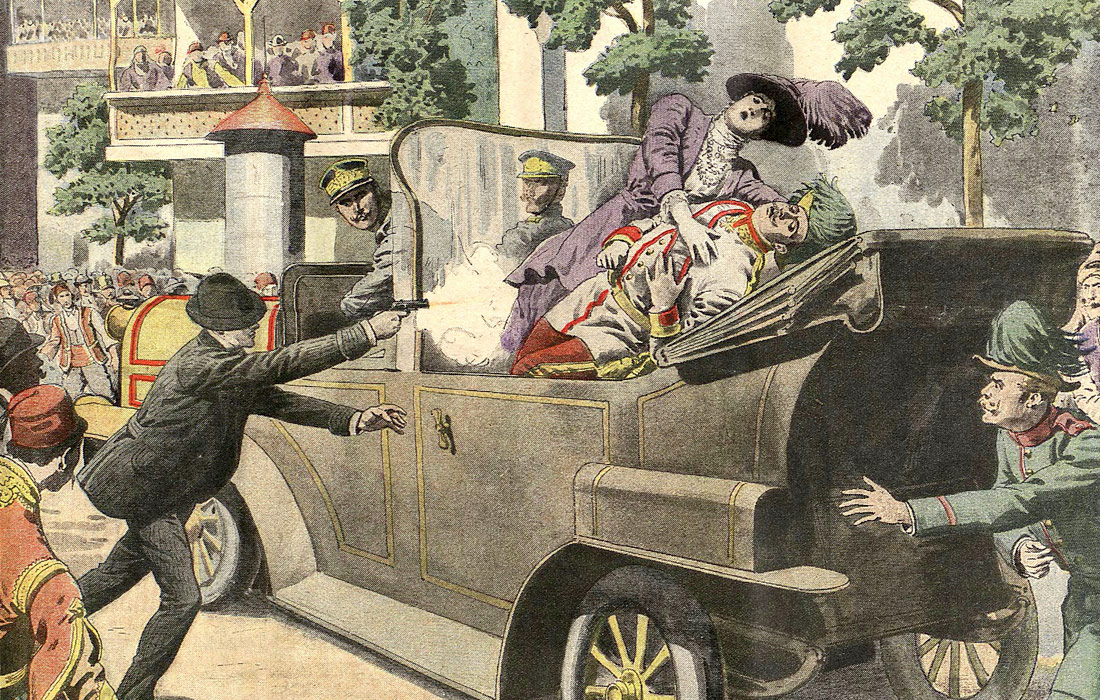

It has become customary to say that the 20th century began in 1914, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo. The magnicide is narrated with the prose and technique of a novelist by Christopher Clark in his superb text The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914 (published in Spain as Sonámbulos. Cómo Europa fue a la guerra en 1914 – Galaxia Gutenberg, 2014). The first terrorist took out his bomb but fear paralysed him. The second was able to toss his explosive, but it either bounced against the car’s convertible cover or alternatively the imminent victim himself was able to bat it away with his arm. Gavrilo Princip, the third, did not waste his opportunity: taking advantage of the fact that the driver took a wrong turn and had to manually reverse the car, he managed to get up close to the Archduke and fire two shots at point-blank range. We could say that the First World War began, among other reasons, because the reverse gear had not yet been invented.

Clark writes that “The assassinations in Sarajevo, like that of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, were an event with a flash that froze people and places at an instant and etched them in fire on the memory”. He also writes that the conflict that began that summer “mobilised 65 million soldiers and took down three empires with 20 million deaths between the military and civilians and 21 million wounded”. As much for its impact on the personal memory of the world’s population as for the geopolitical consequences, it has also become customary to affirm that, nearly 90 years later, 11 September 2001 was the start date for the following century. If the 20th century began in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War, the 21st had its starting shot with another terrorist attack, which changed the entity and the scale of the victim: from a political and military leader, unique and individual, to the collective architectural icon – the Twin Towers – and close to 3,000 people. Among its after-effects, the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, ISIS, the drones war, the massacres in Madrid, London and Paris, and a long et cetera.

Although the First World War would of course alter the artistic representation systems (recall, for example, the magnificent exhibition at the Thyssen Museum, 1914! The Avant-Garde and the Great War, the collapse of the World Trade Centre more quickly and radically affected the perception and retransmission of the real, because of the technological and media context in which it took place. It was perceived, in fact, right at the time that it was happening, like a simultaneous fracture in the order of reality and in that of representation. Or not exactly at the time it was occurring, because its viewing was mediatised by our televisions. And by the news teams of the channels and the news agencies. And by the camera operators, producers, and editors. Real Time, so typical of our era, in reality never is “the real time”: not only is there in its texture a delay or a difference (that is why we often hear our neighbours cheering a goal that we have not yet seen) but it is also marked by a construction (a piece of craftwork, so fast that it is confused with the live broadcast, making us forget that everything is by nature perceived indirectly and mediatised).

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, 1914 | Le Petit Journal, Bibliothèque nationale de France | Public Domain

That construction, that craft, that audiovisual representation technique has its own genealogy. A genealogy that could start back in 1955, with the opening of Disneyland, the first place in the world that was born simultaneously as a space and a television programme. As recalled by Michael Sorkin in Variations on a Theme Park (Variaciones sobre un parque temático – Gustavo Gili, 2004), Walt Disney, faced with problems to completely finance the works of his multicolour utopia, reached an agreement with the channel ABC to broadcast The Mickey Mouse Club. In other words, he sold his most prized possession: his famous mouse. And he gave birth, in parallel, to a physical, concrete theme park, and a pixelated and ubiquitous theme park. Perhaps the first step towards what would later become called the reality show was thought up in those same years by another American visionary, Hugh Hefner, as a multimedia expansion of his most important project: the Playboy Mansion. According to Beatriz Preciado in Pornotopía. Arquitectura y sexualidad en “Playboy” durante la guerra fría (Anagrama, 2010), the magazine, television and cinema were windows that allowed men who were located many miles away to observe what was going on inside the most desired house in the world. “The lounge also served as a model to design the set where they would shoot the television programme Playboy’s Penthouse, which started to be broadcast in 1959 on WBKB Chicago’s Channel 7”, says Preciado. It was a simulation of the meetings of Heffner with his famous friends. It eliminated the whole dimension of a female residence and brothel from the mansion: it focused solely on the hetero-patriarchal and bio-controlling sphere, which was at the same time a real lounge and a television set.

In the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, there was a proliferation of hidden camera programmes and documentary series such as An American Family (1973), Cops (1989-) and The Real World (1992-), that led towards the explosion of reality TV at the strict turn of the century. Concepción Cascajosa Virino and Farschad Zahedi in Historia de la televisión (Tirant Humanidades, 2016) explain that its emergence “as a dominant genre in American television coincided with the incorporation of competition components.” Although Expedition Robinson is a programme of Swedish origin, premiered in 1997, and Big Brother aired for the first time in the Netherlands in 1999, it was their American versions that marked the start of the first golden age of reality TV, in the year 2000. CBS is still broadcasting Survivor and Big Brother to this very day.

Also broadcast in 1999 were the first seasons of The Sopranos and of The West Wing, the dramas that initiated an unprecedented phase of extraordinary quality and greater presence of drama series in the narrative sphere of our everyday lives. So the global impact of the fall of the Twin Towers was fuelled by representation systems that, based on the traditional narrative mould of television news programmes, were being fed by the contributions of two new major genres: intelligent and complex television drama and reality TV. Within the new scenario of mass global attention to the media, in order to follow the news and the consequences of 09/11, these two spheres grew ceaselessly. Today we find whole channels exclusively devoted to quality television series and reality TV programmes, with mutual feedback from the social media networks, and whose essence is the live broadcasting of the ups and downs of subjective experience, the exchange of information and the discussion of shared fictions.

Fireball erupting in the South Tower, World Trade Center, 9/11 2001 | Robert J. Fisch | CC BY-SA

Éric Sadin talks in his extremely interesting essay La humanidad aumentada. La administración digital del mundo (Caja Negra, 2017) about the “end of the digital revolution” and the instatement of an “anthrobology”: it is “at the start of the second decade of the 21st century, that we can date the epilogue of the digital revolution that began at the dawn of the 1980s. This revolution was marked by an expansive movement of digitalisation of industrial objects and information management protocols. It was a movement of exponential propagation and infiltration, which today has been consumed in a miracle of a “comprehensive interconnection.” The pixel is increasingly real and reality is increasingly pixelated. Our own body is a hybrid: we have more awareness of our mobile telephone, which we feel as it vibrates in our pocket even when we’ve left it on the bedside table, than of our spleen or our shoulders. And there is no movement or desire or action that is not quantified, stored and tracked in that parallel and digital dimension that occupies the place of the shadow of each human being (where in magical thinking our soul was once to be found is now where our data is to be found).

Sadin says that we have moved on from the “humanist subject to the algorithmically-assisted individual” and that this means “the definitive agony of modern anthropocentrism”. I agree: from “I think, therefore I am” we have moved on to “I’m connected, therefore I am”. From man as the centre of the world we have moved on to man as a node in a network. Perhaps for that reason, the great nervous tic of our time is the selfie: because in the collective subconscious there is a major resistance to accepting that agony. An agony that coincides with climate change and awareness of the Anthropocene. With the Industrial Revolution a new geological era began, characterised by the radical transformation that man has made of the Earth. Paradoxically or no, as Humanity we are more relevant (more barbaric) than ever, at the same time that we are increasingly less important as individuals.

Let’s go back now to the initial question: When did the 21st century begin? If we follow the pattern of the 20th century, the answer is simple: on 11 September 2001, when a world event took place that was capable of generating drastic changes, symbolically similar to the magnicide in Sarajevo in 1914. But if we seek new patterns for new times, the answer ceases to be automatic. The date 09/11 would never have held the significance it does without the prior creation of a representation system that has its great symbolic date in 1999: the year of the premiere of Big Brother, The Sopranos and The Matrix (and also, by the way, the year in which Kevin Ashton proposed at the MIT’s Auto-ID Center the concept of “the Internet of things”). And if we leave aside the New York attacks, we can still find another two key years that perhaps represent the birth of the century: in 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed, and in 2016, the Working Group on the Anthropocene formally requested that the International Union of Geological Sciences confirm the existence of that new era. Our own.

Walter | 27 December 2022

Muchas gracias Jorge, me pareció muy interesante poder entender el comienzo de un siglo a raíz de la impronta de la historia.

Saludos.

Leave a comment