Thalia Bell, Home Demonstration Agent, operating radio. Tallapoosa County, 1926 | Auburn University Libraries Special Collections and Archives | Public Domain

The development of the information society is based on the more or less conscious belief that technology in itself improves people’s lives. It’s a plausible narrative, but one that does not always take into account the more controversial – and little debated – aspects of this historical and cultural process. The work of artist and writer James Bridle is situated on the less visible side of the digital revolution and puts some of its excesses under the spotlight. Taking advantage of his visit to the CCCB as a guest at The Influencers festival, we review his most prominent projects.

Despite concentrating enormous economic power and providing a previously unimaginable capacity for control, the technology system is generally viewed favourably. Its image as a driving force of development and progress survives the passing of the years, unlike other spheres of the economy such as banking and property. All this is despite externalities such as data extractivism, governmental surveillance, military applications or, more recently, the threat of the mass destruction of employment.

Artist and writer James Bridle has based the greater part of his career on revealing the intricacies of new technologies, especially of those linked to political and military power. With a focus that is non-apocalyptic and not even pessimistic, this Briton resident in Athens advocates knowledge as a necessary condition for evaluating reality. “We live in a world shaped and defined by computation and it is one of the jobs of the critic and of the artist to draw attention to the world as it truly is”.

Assaulting the skies

If the cliché is true and the 21st century really began with the collapse of the Twin Towers, James Bridle is undoubtedly an artist of the third millennium. Born in 1980, his younger years passed between the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, terrorist attacks in the country of his birth, the war in Syria and the birth of ISIS. His work drinks from a context of tensions between security and freedom, a space of blurred frontiers where there has been a proliferation of some rather concerning technical artefacts: military drones.

Unmanned combat aerial vehicles are weapons designed to carry out selective attacks or espionage missions without the need for a pilot. Due to their small size, military drones can act in enemy territory without detection or attracting attention. For a time, this physical invisibility was replicated in the media. The Western press did not report on their use until approximately 2012, despite such aircraft having been employed in countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan since 2004.

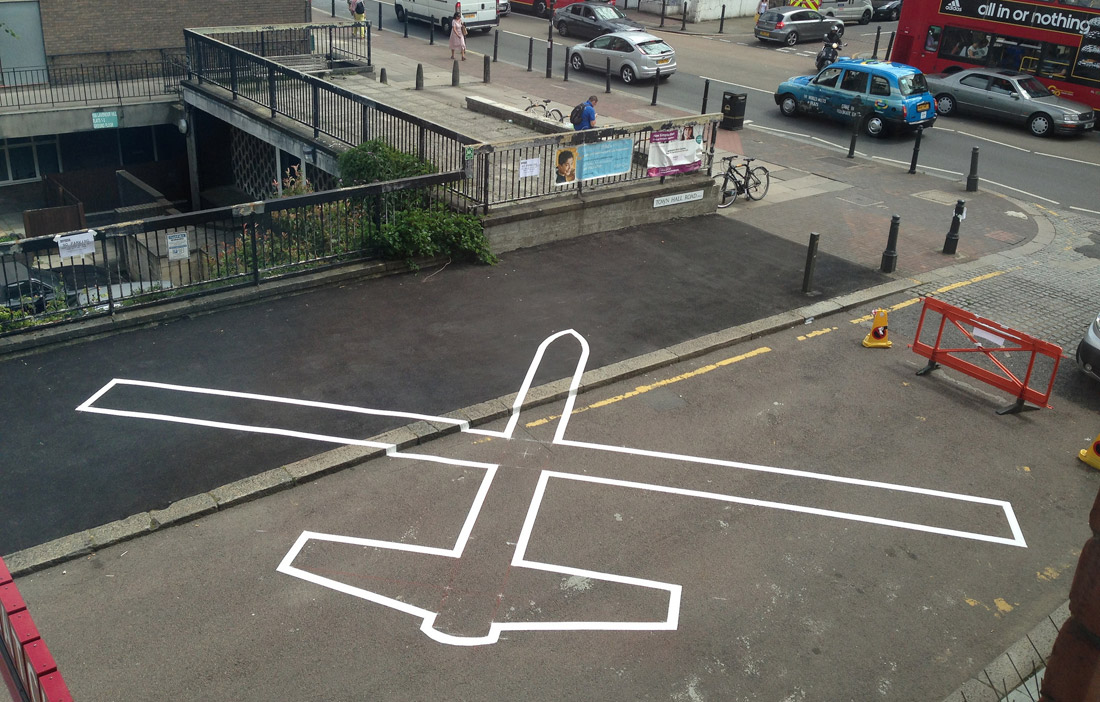

James Bridle’s work began as a response to this lack of information. Drone Shadows, one of the first projects on the issue, responded to a simple question: What would it be like to be next to a drone? In 2012, photographs of this type of weapon were practically non-existent, so it was difficult to imagine their scale or level of technological sophistication. After carrying out an investigation into their measurements and appearance, the artist started to draw outlines of these aircraft in public spaces, in an attempt to make them more visible to passers-by. In a parallel line of work, he opened Dronestagram, an Instagram account with images of the exact coordinates where attacks were documented. In this case, the question implicit was different: why do we know so little about the places and people that our governments are bombarding?

Drone Shadow 007. London, 2014 | © James Bridle

In parallel with his work on military drones and prior to the expansion of these tools for domestic and civil use, Bridle began a line of investigation with home-made helium balloons which he called “drone prototypes”. He used them as a medium to start exploring ways of counteracting the use of police aircraft, as well as of obtaining independent and self-managed aerial images. His most prominent project in this sphere is The Right to Flight, the installation of a balloon suspended over the sky of London for four months. The device was equipped with cameras and routers that enabled it to communicate data in real time to anyone who requested it. At the same time, the British artist organised workshops and conferences on the playful and political possibilities of citizen aerial photography, as well as its relationship with mapping and governmental surveillance.

The map and the territory

Although it is not evident, aerial photography has implications in the perception of the physical space. Digital map services show the user, carrier of a GPS signal, as the centre of the world, but they also establish a type of perspective and power relationship based on who has the technical capacity to capture images from the sky. In an attempt to deconstruct this way of viewing, James Bridle has developed works such as Rorschmap and Anicons, which offer a new cartographic aesthetic. In the hands of these applications, the captures taken by homemade balloons or satellites are transformed into kaleidoscope images, recovering the beauty and the meaning of discovery of the first atlases.

The fight over aerial photography also reflects tensions on ground level, especially when used for security purposes. Bridle’s generation – let’s remember, that of No to War, in England too, as well as the Occupy movement – has learned by force that the public space is not public in all accepted meanings of the term. On certain occasions, the State may deploy its authority over the land to claim its hegemony, especially when it is used for unforeseen purposes. “It’s at such moments”, Bridle writes, “that the real structures of city life become visible: a matrix of permissions and observations, many of them unreadable most of the time”.

The tension over the control of the space is also made evident by the proliferation of public and private video surveillance systems. The artist has worked on this issue in different formats (Every CCTV Camera, The Nor), including walks around London in which he photographs and records all the CCTV cameras that he finds. In this kind of Situationist drift, Bridle counted up to 140 cameras in a single walk of 1.4 miles. And as if the sensation of being spied upon were not enough, the police questioned him on one occasion after he was seen wandering around taking instant photos. As he himself later ironized, he was stopped on suspicion of “the potential crime of paying attention”.

Migration and citizenship in a virtual world

The veto on what is visible and transitable covers public and private spaces but also extends to administrative processes. In Seamless Transitions, a 2015 project on the deportation of immigrants, Bridle discovered that it is illegal to photograph the detention centres and courts used in Great Britain to carry out repatriation. This network of facilities, paradoxically, features luxury lounges and private aircraft. The reason: commercial airlines do not want to transport passengers under duress, especially after the death due to cardio-respiratory failure of an Angolan citizen who was being deported to his country in 2010.

With the aim of evidencing the existence of these spaces, James Bridle got hold of plans and satellite photographs, interviewed academics and activists, and worked with a buildings visualisation agency in order to recreate them. In this way, and although the result is only a virtual representation in 3D, the artist sheds some light on these inaccessible corners, while revealing how the British immigration system functions.

Although Bridle has specifically worked on the issue of immigration and the refugees crisis in Europe, his reinterpretation of the concept of citizenship in a broad sense is remarkable. This is the central theme of Citizen X, an extension for browsers that tracks where the servers of websites visited on the Internet are located. The tool shows the locations in real time and draws a flag with the fragments of these nationalities. A simple but effective proposal that confirms a new form of citizenship: algorithmic citizenship. In this new way of inhabiting the world, people’s freedoms and rights are calculated, rewritten and questioned based on their internet browsing; in a way that is imperceptible for the user but accessible – although in an aggregated way – for governments and businesses.

Giving form to progress

“The personal is political” was one of the most popular maxims of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s. It was used to make manifest that the systems of oppression against women are not only articulated in the economic or legal sphere; everyday life too conceals relations of power that need to be revealed and fought against.

For James Bridle, the technological is political. New technologies are interwoven into the very nature of today’s society, which means it is necessary to wonder about their design in terms of power. Drones, CCTV, servers, are just technical gadgets, it is the legal and political systems that give them form and enable them to operate in one direction or another.

“Technologies are stories we tell ourselves – often unconsciously – about who we are and what we are capable of,” writes James Bridle in a recent essay, “but they are not in and of themselves future-producing, magical or separate from human agency.” With his art and his critical work, this British artist advocates the duty of citizens to give shape to progress, a task that appeals directly to our critical capacity in the face of the lights and shadows of the digital revolution.

Nil | 24 October 2017

Sin duda las nuevas tecnologías son hoy por hoy los brazos de este capitalismo demoledor. Sin embargo, debemos y podemos, apropiarnos de esta revolución tecnologica para cambiar las cosas.

Puede que sea de vuestro interés https://tecnologiasparaelcambio.wordpress.com/

Leave a comment