The shepherd night watch reads the stars to know the hour | Library of Congress | Unknown use restrictions

From fake news pieces to hyper-realistic video and audio fakes, the credibility of information in the digital age is constantly being called into question. Beyond the success of the term “fake news”, we ask how disinformation works and what role traditional media can play in this scenario of mistrust.

There’s a folk tale that tells of a young shepherd who, to amuse himself, tricks the people of his village by crying out “wolf!”. The moral of the story is that the shepherd loses his credibility, and when a wolf really does come along, nobody runs to help him and it attacks his sheep. This may be a classic example of fake news, albeit that nowadays, spreading disinformation doesn’t generally result in the liar losing out.

Although the term “fake news” had been used before, it came into vogue after the 2016 United States presidential election. Seeking explanations for Donald Trump’s victory, many voices pointed to the spread of fake news over social media. The term skyrocketed on Google searches between this election and February 2017. It reached new heights in January 2018, when Trump presented his Fake News Awards to media outlets that showed him little sympathy, in October of the same year, when Jair Bolsonaro won the Brazilian elections, and finally, in March 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fake news has become a dominant theme in politics and communication, to the point where it is generating moral panic, according to Matt Carlson. Following the definition of Stanley Cohen, a moral panic, says Carlson, occurs when a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests. These threats may or may not be real, but what interests the two researchers is how panic builds up around them.

The explosion of deepfakes

At the beginning of 2018, these concerns were intensified by the appearance of a new phenomenon: videos that used artificial intelligence to replace a person’s face with someone else’s to incredibly realistic effect. The technique, known as deepfake, initially attracted attention for using a technological development to facilitate sexual violence when users included the faces of celebrities, or anyone they wanted to attack, in pornographic videos.

Soon we began to see this technology put to other uses, all of them quite impressive. These include more or less harmless applications, such as having Jim Carrey star in The Shining instead of Jack Nicholson, or resurrecting Lola Flores so she could appear in a beer commercial. But seeing that a video of the President of the United States could be created from nothing more than an audio track generated far more concern. More recently, we have seen it used – albeit with very little technical expertise – to fake a statement by Ukrainian president Volodymir Zelenski during the Russian invasion.

Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron, specialists in digital law, have published a noteworthy article that analyses the challenges posed by this new technology. As well as swapping faces, they consider a deepfake to be any form of hyper-realistic digital forgery of images, video or audio.

Doctored imagery is neither new nor rare. Innocuous doctoring of images— such as tweaks to lighting or the application of a filter to improve image quality—is ubiquitous. Tools like Photoshop enable images to be tweaked in both superficial and substantive ways. The field of digital forensics has been grappling with the challenge of detecting digital alterations for some time. Generally, forensic techniques are automated and thus less dependent on the human eye to spot discrepancies. While the detection of doctored audio and video was once fairly straightforward, the emergence of generative technology capitalizing on machine learning promises to shift this balance. It will enable the production of altered (or even wholly invented) images, videos, and audios that are more realistic and more difficult to debunk than they have been in the past.

As an example of the latter, we can refer to the random face generator on the This Person Does Not Exist website, created by engineer Philip Wang with the same technology used to create deepfakes – a generative adversarial network. Chesney and Citron point out that, with technology like this, where there are no major barriers to access beyond learning how it works, the creation of deepfakes is increasingly within the reach of anyone.

The credibility of the media

Matt Carlson’s study focuses on the discussions around disinformation in the traditional media, and explains that, when the issue exploded at the end of 2016, they pointed to fake news as a threat to democracy, but at the same time, on the back of the controversy, they defined which sources of information should be respected: traditional newspapers and news programmes.

According to the accounts gathered by the researcher, the fault of the problem could lie with those who created fake news for shady purposes, the social media on which it was shared, the economic benefits that could be obtained from attracting audiences with fake content, or even the irresponsible consumption of news by users themselves. The answer, in any case, according to these discourses, is the traditional media. There, many journalists argue, is where credibility can be found, and when someone cries wolf over any other platform, they may well be deceiving us.

The difference between fake news and real news, however, is a thorny issue. Researcher Claire Wardle is one of the leading voices in the debate on how we should think about disinformation in our time, and in a report written with Hossein Derakhshan, she points out the dangers of the term “fake news”:

The term “fake news” has also begun to be appropriated by politicians around the world to describe news organisations whose coverage they find disagreeable. In this way, it’s becoming a mechanism by which the powerful can clamp down upon, restrict, undermine and circumvent the free press. It’s also worth noting that the term and its visual derivatives (e.g., the red ‘FAKE’ stamp) have been even more widely appropriated by websites, organisations and political figures identified as untrustworthy by fact-checkers to undermine opposing reporting and news organizations.

Trump’s Fake News Awards are a clear example of this. He turned the term around to attack precisely those media outlets, such as CNN, The New York Times and The Washington Post, which claim to be bulwarks against the rise of disinformation. The fact is that the awards of the then POTUS named news items in these media that did in fact contain incorrect information. All of them had been swiftly corrected, long before the awards “ceremony”, and with apologies from the media outlets and journalists who had published them. Therefore, they reflected a very different intention from that of websites created for the exclusive purpose of publishing fabricated news against a political opponent. Even so, for Trump, the inclusion of erroneous information was enough to warrant the red “FAKE” stamp and an attack on the credibility of these media.

Announcement of the Fake News Awards published on the US Republican Party website and subsequently removed.

The liar’s dividend

In this vein, Chesney and Citron identify a very notable danger in their study of deepfakes. Not all lies, they say, involve stating facts that never happened, but rather lies are very often told to deny truths. Deepfakes make it easier for the liar to deny the truth. On the one hand, people can use adulterated audio or video material to counter accusations, but on the other hand, there is an even bigger danger:

Ironically, liars aiming to dodge responsibility for their real words and actions will become more credible as the public becomes more educated about the threats posed by deep fakes. Imagine a situation in which an accusation is supported by genuine video or audio evidence. As the public becomes more aware of the idea that video and audio can be convincingly faked, some will try to escape accountability for their actions by denouncing authentic video and audio as deep fakes. Put simply: a skeptical public will be primed to doubt the authenticity of real audio and video evidence. This skepticism can be invoked just as well against authentic as against adulterated content.

The outcome of this danger is what they have termed ‘the liar’s dividend’, a benefit that “flows, perversely, in proportion to success in educating the public about the dangers of deep fakes”.

As a society, we have the challenge of dealing with new forms of disinformation, but we also need to think about how we do this. If, as Matt Carlson argues, the discourse of the traditional media is more concerned with defending its own role and whipping up panic than helping to understand the dynamics of disinformation, we are on the wrong track.

In this context, fact-checking initiatives have mushroomed, with sections or new media aimed exclusively at verifying whether certain claims are true or false, and they can be a useful tool, but they also have risks. For example, a careful analysis is required of whether the fact of denying false information could further spread it, or whether the information is sufficiently widespread to warrant attention. We also need to be clear about which statements are verifiable and which are matters of opinion.

Moreover, the media should be careful not to fall into the “everyone’s lying” logic as a way to balance the diversity of political options. It’s common for the media to try to debunk a balanced number of claims from across the political spectrum, such as when The Washington Post equated Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez with Donald Trump, comparing the former’s miscalculations with the latter’s blatant lies. Or when El País “half debunked” the then Podemos candidate, Pablo Iglesias, during a debate on the grounds of what was really a terminological issue, before finally having to backtrack. This ideal of balanced journalism only reinforces the general feeling that nothing can be trusted.

Chesney and Citron point out that this atmosphere of distrust simply feeds authoritarianism:

The combination of truth decay and trust decay accordingly creates greater space for authoritarianism. Authoritarian regimes and leaders with authoritarian tendencies benefit when objective truths lose their power. If the public loses faith in what they hear and see and truth becomes a matter of opinion, then power flows to those whose opinions are most prominent—empowering authorities along the way.

If we go back to the story of the shepherd who cried wolf, it is possible to imagine how another shepherd, who had never lied, might be ignored by his neighbours when he cried out for help after the lies of the first shepherd. So, the moral of the story, apart from the importance of preserving our credibility, could be that when we no longer trust anything, the wolf wins and we are all lost.

Rethinking disinformation

For Matt Carlson, all the panic generated by fake news

is also an uncomfortable development for the largely for-profit journalism industry in the US that has long relied on attracting audiences through a variety of content – much of which falls outside the public service ideals of hard news. This is not to equate the content of fake news with all news, but to pinpoint the structural similarities that encourage attention-grabbing content.

The answer to this whole problem of disinformation should not be blind trust in the traditional media. Because they also use clickbait, they have their biases, they are sometimes wrong, and because many people have studied and pointed out how they tend to reproduce society’s prevailing values and to make certain facts invisible. The answer should involve an understanding of how the media works and how disinformation works, beyond the success of the term “fake news”.

Wardle and Derakhshan propose a map to understand the problems associated with what they call information disorder. We need to be able to identify three types of false or intentionally harmful content:

- Mis-information. This includes false information, but where no harm is meant, like the “fake news” named by the Trump awards or Ocasio-Cortez’s miscalculations.

- Dis-information. All content that incudes false facts – from modifying the context with a real image to a completely made-up headline – and which is intentionally harmful.

- Mal-information. Content which, while it isn’t false, is spread with the aim of causing harm, for example certain information leaks or content spread as a form of harassment.

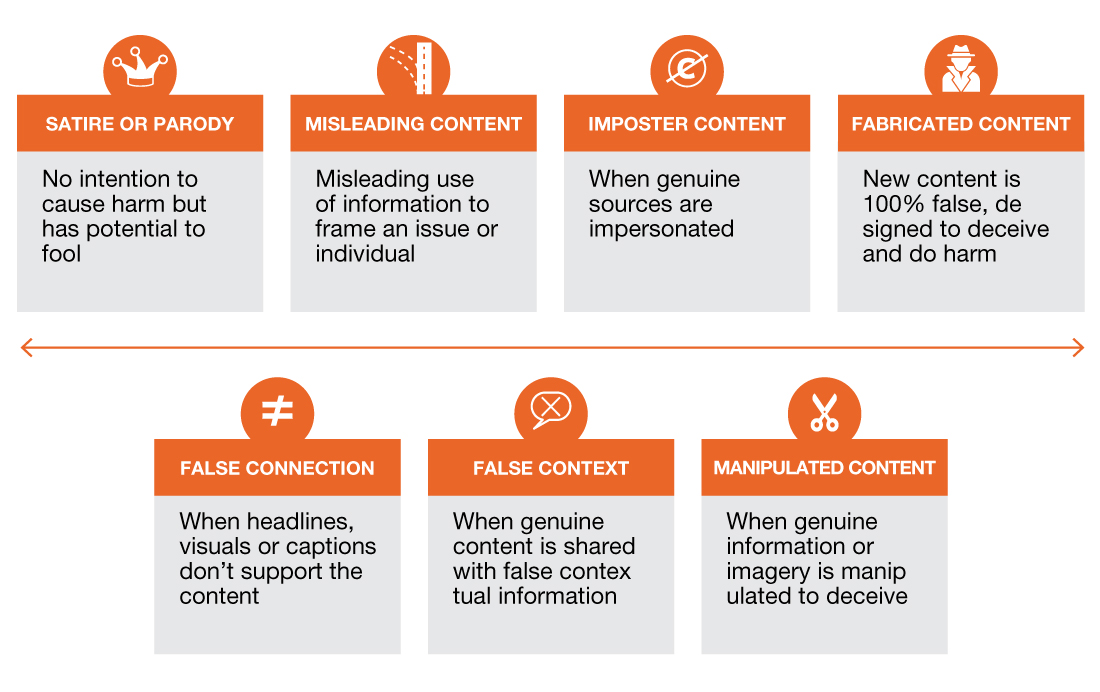

In addition to this, Wardle has developed a terminology set for referring to different types of mis- and dis-information without having to resort to talking about “fake news”.

CC-BY-SA 3.0 UNESCO

If we have a clearer idea of what it is that we are criticising in each piece of content, we can build a clearer consensus regarding what we are talking about, move beyond mere opinion and construct a more productive debate about the media. We must speak in the right way to avoid the panic and imprecision of the cry of “wolf” that is fake news.

Leave a comment