South African artist William Kentridge does not trust those who blindly embrace their own certainties without considering doubts and paradoxes. Ambiguity and contradictions are at the heart of his work, which has grown and transformed to the beat of multifaceted South Africa. We talk to the South African artist about segregation, the echoes of colonialism and the anti-racist struggle, about imbalance and abuse of power, privilege and the role of art in rethinking dominant narratives.

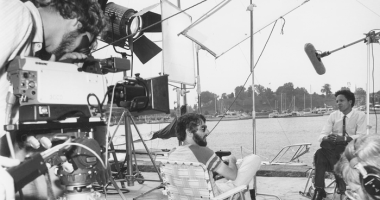

I have been swallowed up by the Kentridge universe. For years I have navigated his city and made it my own, Johannesburg, the landscape of and a character in his work. But now I’m literally on his creative planet: in his studio full of iconic, recurring objects in his mobile and immobile pieces. There is the megaphone, the ladder and the coffeepot. There are perspective calculations on the blackboard and there is also him, William Kentridge, one of the world’s most influential contemporary artists (one of 51, to be precise, according to Art Review). I am—we are, with the film crew—in his space, suspended in an impeccable garden in Johannesburg. The studio is open-plan and organized. Radiant. Very black and white, with hints of clay. Like his uniform: black trousers and white shirt with paint stains—traces. Life and history leave traces, and he considers it important to show them, not hide them.

Outside, there is a lush lawn, with flowers and bees and birds. And a wall separating the house from quiet, elegant streets; in his neighbourhood of Houghton, many houses are mansions. The few who walk there are domestic workers and gardeners. Black. In Johannesburg, a city divided from the outset, whites were assigned to live “where the gardens and watering systems are, segregating blacks into townships”, says Kentridge as he walks around the studio. In this way, “not just wealth but also resources were focused on the white suburbs, while deprivation and shortages marked all other areas of the city”. The city is physically designed to ensure barriers and divide spaces. And that distribution has changed “only to a certain extent” since the end of apartheid, 26 years ago. “Essentially, the beautiful gardens are still in formally white neighbourhoods, and the townships are still poor and under-resourced. So I’m very aware of the privileged space in which I work”, he concludes, constantly gesticulating.

To be praised as one of the most representative artists of the South Africa of change, which breaks with legalized racism and apartheid, as a white man is, to say the least, paradoxical. But of course racist and sexist policies do benefit individuals of a given race or gender, even those who reject the idea. Despite being critical, their voice is stronger, more powerful, more protected, and their talent can therefore grow and expand in all its glory. Kentridge’s genius has been able to reach the pinnacle of world contemporary art, just as the writing of Nadine Gordimer and John Maxwell Coetzee—also anti-apartheid South African intellectuals, also white—has won the Nobel Prize for Literature. They are not the ones who are there, but the ones who are no longer there, the ones who present the evidence of racism—with and without laws.

William Kentridge does not shy away from the paradox; he rides upon and shares it. When I ask him about his relationship with privilege, he raises his eyebrows and says that to winkle out an answer I might need to be his psychoanalyst, but he is honest with his position. “The perspective of my work is basically mine”, he says, and the complexity that surrounds it slashes it wide open. Inspection reveals a body of work that is vast and acute, complex and original, of canvases and tapestries, of charcoal and film. He is a theatrical and animated, critical and analytical artist. And, climbing and combining techniques of stage, performing, graphic and sculptural arts, he presents an explosion of contradictions and ambiguities, with him and Johannesburg both at the centre and in the lines: he the person, he the artist. He, a man, white, filming himself, looking at himself in a segregated, racist, mining, brave city that was born with a fever—when gold was discovered—that has never abated.

Racism in Johannesburg and South Africa is written in bold text, for the short-sighted—the same essential, systemic racism that works globally, put on display and with explanations in the footnotes. Colonialism, slavery, racism. For the artist, “It’s incredible that 150 years after the end of the transatlantic slave trade and 60** years after the independence of African countries, the residue of colonialism is still so strong”. You just have to scratch the surface to see that “there are fault lines coming from that period throughout the world”.

Apart from being the year of COVID, 2020 was also the year of #BlackLivesMatter: a massive global outcry against the powers that, using different mechanisms, have continued to murder George Floyds, Steve Bikos and Patrice Lumumbas century after century; millions of homicides, legalized or a-legalized or erased. From the chains of shipped African slaves to the mass incarceration of African Americans explained by Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow and Ava DuVernay in the documentary 13th, a reference to the amendment of the US Constitution that abolished slavery except as a punishment for conviction of a crime (the latter can be seen on Netflix).

But deep down, the Black Lives Matter movement “has placed in the spotlight a struggle that’s been fought for generations” and which, in South Africa, Kentridge thinks, is in the fore, because the anti-apartheid struggle “was about that” and because these “central issues, that appear and disappear, in South Africa have always been clear and on the surface, taking form in different ways”. The student movements Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall (calling for the removal of colonial symbols and demanding the decolonization of knowledge at the university) were, for example, “a new and intense way of tabling the debate”.

If these are struggles that emerge—with varying impact—on a recurring basis, if they are like cyclical phenomena, if this is just the turn of a vicious circle, is it realistic to expect substantial changes? I’m surprised to hear him say with conviction that “we won’t go back to where we were before”. Despite his gift for the abstract and his affinity with ambiguity, he says that having evidence of who the powerful people are and how they have operated around the world is generating change.

So, while arguing that being optimistic or pessimistic is false because it means “blinding yourself to some things”, Kentridge believes in change. He thinks that “assumptions which people had before can no longer be held” because “people can’t pretend ignorance of the larger questions anymore”.

Because, for Kentridge, it’s very clear if you’re outside the West what is happening: “For hundreds of years Europe amassed immense wealth through which it was able to have fantastic infrastructure, great education, great health systems and social welfare.” And now that a small percentage of the population from which they took all that wealth “wants to come to Europe to try to share in those benefits, barriers are put up”. ”We’ve taken everything”, he says, separating himself for a moment from his African origin, “and now we put up a wall to make sure no-one gets near it again”.

In the face of the uproar of protest, there is of course “this huge reaction in America and in Europe, and very right-wing populist leaders come to the front”. The fight to protect privilege is “a rear-guard action, this extreme reaction”, “and it always has to do with generating the most ungenerous and the most selfish elements of all people in those societies”.

William Kentridge was born the same year as Black Sash, a white women’s movement that opposed segregationist policies. The same year that, despite restrictions on education, Winnie Madikizela (later Winnie Mandela) became the first qualified black social worker in the entire country. Apartheid had been in force for seven years, and prohibitions and forced displacement were in full swing. Winnie started working in Soweto, while in Houghton, in the same house with the lush garden where we are talking today, the Kentridges cradled their new baby.

The Johannesburg of Sowetos and Houghtons, of protests and police brutality, trumpets and prolific musical creation, has always provided the beat and the framework of Kentridge’s work. The macro-city, so young but packed with memories, “is an animation in itself, which erases, redraws and reconstructs itself” and, emulating it with his famous, constantly changing drawings, Kentridge has come up with a multifaceted art as kaleidoscopic as the city itself—which I have also somehow made my own and which is also that of Trevor Noah. And, like the mother of comedian Trevor Noah, bypassing the absurd barriers created by a group of white men by renting an apartment in the city centre and educating a son forbidden by law (Noah was the product of a mixed relationship and was, therefore, born a crime), William Kentridge questions the barriers of the art world, navigating between disciplines but also tearing down the toll gates of creation. His Centre for the Less Good Idea is an incubator for upcoming artists, a collaboration project where thought is open to different voices.

A lot has happened to Soho and Felix, Kentridge’s most famous duo, since the characters emerged, in a dream, on the eve of the fall of apartheid. These main characters in the Drawing for Projection series have been lively witnesses to South Africa’s hopes and fears for over 30 years. And they have grown and transformed to the rhythm of a gigantic artist, who, in his stained white shirt, rejects the idea of knowledge and distrusts certainties, because he sees instead “moments of recognition; of understanding what it is we understand”.

And while he understands the impulse of those who want to forget the past, because traumatic memories can actually paralyse you, he is not in favour of it. Because “without understanding the past, there is no understanding of where we are now”, and, for this reason, one of the tasks of the studio is precisely to “try to find a way of encapsulating memory in a physical form”.

It is curious that the last thing I saw at the cinema in Cape Town before South Africa went into full lockdown were some Kentridge animations, accompanied live by pianist Kyle Shepherd, and that, just as we are beginning to catch a whiff of normality, I find myself in his studio, while, in my native Barcelona, the CCCB exhibits his work to invite us to think about our position in this echo chamber where the cries of inequality resonate.

Leave a comment