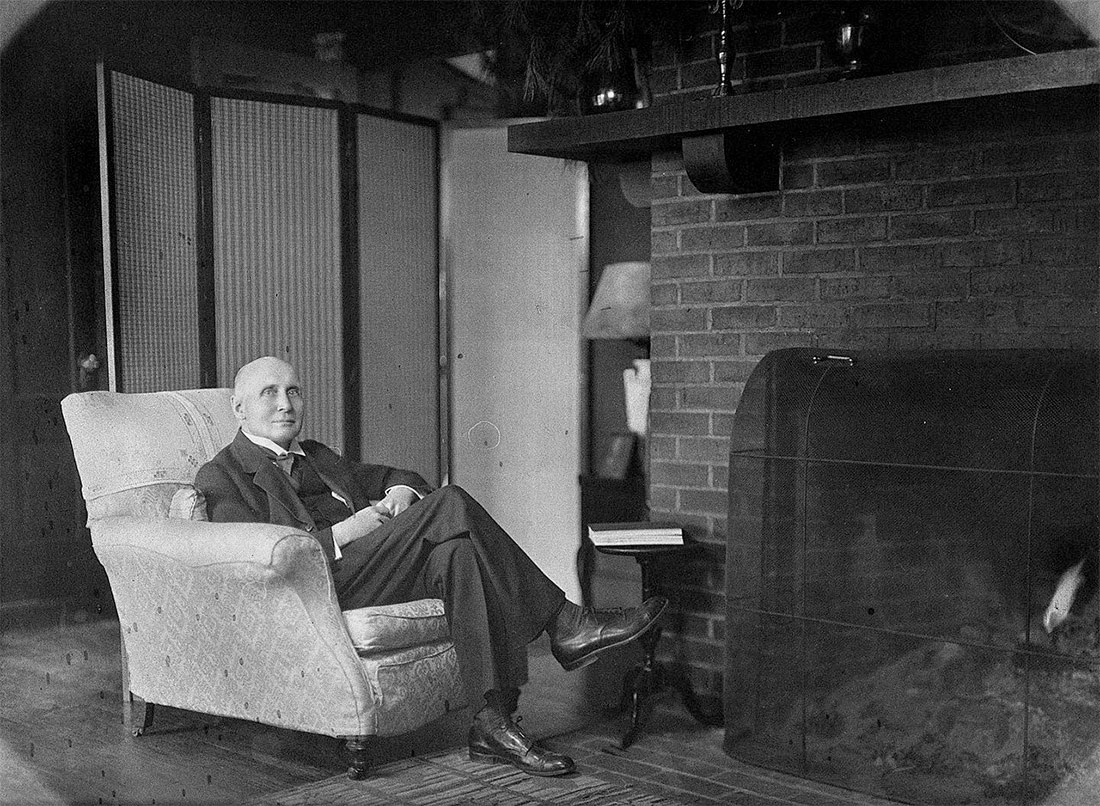

Alfred North Whitehead | Wellcome Images | CC BY

As with all great thinkers, the English mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) can be approached from a wide range of angles and sensibilities. As such, we go on a personal journey of exploration that takes in the previous work of others on the magnum opus of this thinker: Process and Reality, a compilation of lectures published in 1929.

Within the context of the anthropocenic theoretical and practical shift, as well as the drive among some epistemic circles towards blurring the boundaries between the natural and social sciences, numerous contemporary authors have referenced Whitehead in their recent work. The most popular of these include Steven Shaviro, Bruno Latour, Graham Harman and, more prominently, Isabelle Stengers, one of the most influential thinkers of the 21st century. Roughly speaking, the main thesis put forward in Process and Reality that is instrumentalised and discussed by this series of intellectuals deals with the relational character intrinsic to all beings, human and non-human, organic and inorganic. For Whitehead, relationships precede the very condition of being, as explained in more detail below.

For the purposes of contextualising this work, a relevant fact is that the English philosopher closely and enthusiastically followed the discussion that played out during the mid-1920s between Niels Bohr, a physicist of the Copenhagen school, and the Austrian physicist Albert Einstein, on the principles of the quantum event. It seemed that reality always contained an element of uncertainty, something that was unmanageable for modern science. It was under this pretext that Whitehead put together the theory of what he described as ‘speculative knowledge’. He himself explained this in graphic terms: if we see an aeroplane fly out of sight, and in a few minutes the same plane reappears within our field of vision, can we affirm that the plane was flying during the time it was not visible? The answer he gives us is that empirically, no; speculatively, yes.

In attempting to outline the main arguments put forth in Process and Reality, we will look at three major contributions made by the book that are crucial to understanding some contemporary debates on the character of entities in the universe, as well as the relationship between human beings and their material environment, as disciplines such as Science and Technology, Earth Science and Anthropology attempt to analyse. It was in this book that Whitehead introduced his philosophy of organism, which reveals an organic materialism, shifting the understanding of matter from a static configuration to an energy in flux.

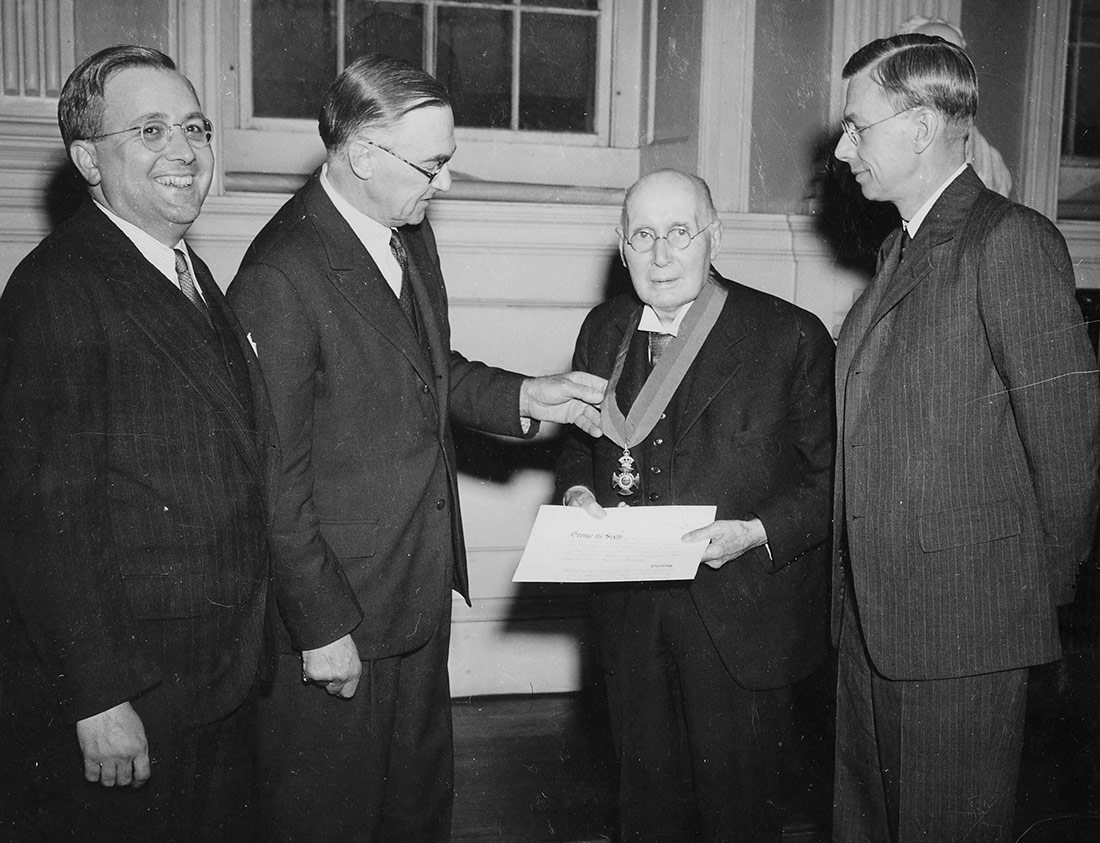

Alfred North Whitehead | Harvard University Archives

The first major task tackled by this work is that of exploring the pillars of speculative knowledge. Whitehead thoroughly read and studied the texts that gave birth to empiricism by Francis Bacon and David Hume, the fathers of modern science. From this foundation of knowledge, Process and Reality exposes the limits of this epistemological rationality, of the irrational faith in the idea that the cause-effect relationship derives from experience. As the book explains, the Kantian categories, which supposedly define the objects of the world, are not dogmatic statements of that which is obvious, but rather tentative generalisations. Speculative knowledge, as contemporary authors such as Quentin Meillassoux have also explained, shies away from reducing reality merely to the manner in which humans experience it and, in an exercise of humility, recognises that this reality is integrally inaccessible to human knowledge. Essentially, Whitehead is making a penetrating critique of the intellectual colonisation of nature, which justifies humanity as the owner of the world and which has given rise to the current systems of economic organisation based on the extraction and disruption of the material world to the edge of exhaustion.

Speculative knowledge opens up careful and sensitive alternatives to the infinite possibilities offered by our reading of the world, beyond the will to conquer of modern science. The anthropologist Anna Tsing, in an act of story-telling, traces the process of commodification of a Japanese mushroom (a matsutake) to reveal the interweaving stories of migrant lives and means of subsistence within the context of what she describes as the ruins of capitalism. Similarly, Donna Haraway uses speculative fables, a narrative practice that aims to distort the perception of reality, to question the conventional ways in which knowledge is produced and to open the door to new worlds through the daily micro-interactions between beings and matter. Speculative knowledge is therefore an invitation to re-imagine the infinite possibilities into which events can unfold.

The book’s second major line of argument looks into the relational character of being, which for Whitehead precedes being itself. In other words, every being is a composite, and therefore the fruit of a relationship. As such, at the genesis of being there is no static element, but a relational process. The author nods to Hindu and Chinese traditions of thought, for which reality is also understood as a process, unlike in most Western traditions of thought, for which the essence of being is a complete and concluded fact. In Process and Reality deterministic causality is replaced by creativity, the very thing that gives rise to the infinite indeterminable collisions that end up moulding the form of the universe. One of the most notable implications of this argument, where relation is the primary condition for all possibility, is currently manifested in new forms of materialism, the critical narrative of the Anthropocene and ecofeminist movements, among others. Ultimately, the relationality of being reveals its dependence and vulnerability, thus inviting human beings to rethink their future, intimately interwoven with their material environment.

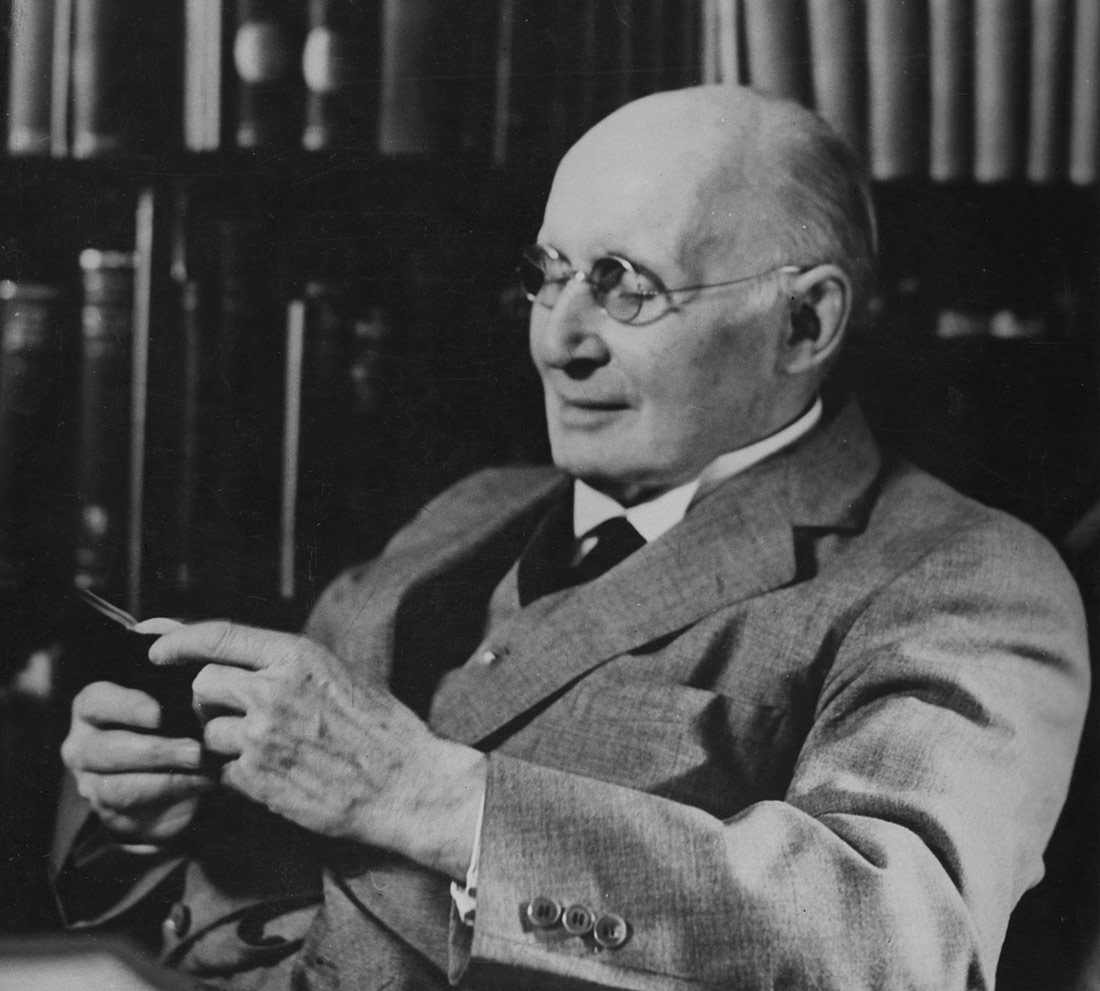

Alfred North Whitehead | Harvard University Archives

Essentially, for Whitehead, relationality is a tool for picking apart Cartesian dualism, which drastically separates the spheres of the (human) subject and object, or culture and nature. This separation bestows an artificial superiority on human beings in the earthly sphere, which over the last three centuries has degenerated into unbridled anthropocentric progress with devastating effects on the planet. This separation has also generated exclusions in respect to race, gender and the canons of beauty, insofar as the subject in the Cartesian imaginary is not just any human subject, but, metaphorically speaking, the image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian: a white and perfectly proportioned Man. Process and Reality astutely rejects what some current authors have described as ‘correlationism’, in other words, the fact that the existence of a (human) subject is a condicio sine qua non for the existence of the world. For the English philosopher, human beings and nature cannot be dissociated: they are part of the same fabric of reality.

Finally, in tune with the relational conception of being, as well as the developments in the quantum domain that he himself testifies to, Whitehead develops a conception of space-time that breaks with Euclidean geometry and Newtonian physics, for which space-time is a linear configuration, a void where human beings evolve progressively and deterministically on an unlimited basis. The English philosopher was notably influenced by Henri Bergson, who suggested that the human intellect has a tendency to ‘spatialise’ the universe and thus to categorise it, ignoring the fact that it fluctuates. In Process and Reality, space-time is described as an extensive continuum, i.e. a relational complex that makes it possible for beings to come into existence. This continuum includes the whole and the parts, points and lines, past, present and future. Contemporary authors have insightfully explored this non-linear, mysterious and bizarre conception of history. Manuel Delanda, for example, argues that time is not a vessel in which events happen, but that ultimately it is these events that generate time. This third line of argument requires a rethink of humanity’s role in the universe, while demystifying the Judeo-Christian teleology that gives meaning and a providential and hopeful direction to human evolution.

To recapitulate, Whitehead offers us highly valuable tools for rereading the events of the present day, from the climate crisis to war. As regards the latter, in a later text, Adventures of Ideas, the English philosopher tells us that the achievement of peace is unfortunately beyond human purpose and will. Peace, he continues, cannot be the source of hope for the future, insofar as it involves infinite variables that can never be fully reached. Believing in the possibility of defining the future simply reproduces the myth of Judeo-Christian teleology, whereby human beings have come into the world for a purpose. And this risky position leads to frustration. Anna Tsing, once again, puts it clearly: we must also accept the possibility that there will be no happy ending. Peace, Whitehead continues, has to be understood in relation to the tragic events that constitute it: peace is thus both the understanding of tragedy and its preservation. Tragedy makes the existence of peace possible. For the English philosopher, the human experience of peace gives rise to a generative force and a creativity that opens up every possibility for the future, including the absence of war. But to neglect the radically open and uncertain nature of events to come can only lead into the abyss. In conclusion, Whitehead, specifically in Process and Reality, invites us to view the world not as a preordained theatre, but as the residue of friction between an infinite multiplicity of possible events.

Gustavo Arteaga | 05 April 2022

Un texto que genera más interés por un autor maravilloso….

Leave a comment