Shopkeeper and a customer considering to buy an axe or an axe handle. Leaby, Sweden, 1940 | Carl Gustaf Rosenberg, Riksantikvarieämbetet | Domini públic

Digital technologies lower costs, increase efficiency and allow for greater specialisation. However, we rarely talk about what we lose with digitalisation, who is excluded in the process or where the limits lie. Often it is older people, with their conscious and informed decisions about digital technologies, who show us the limits of digitalisation.

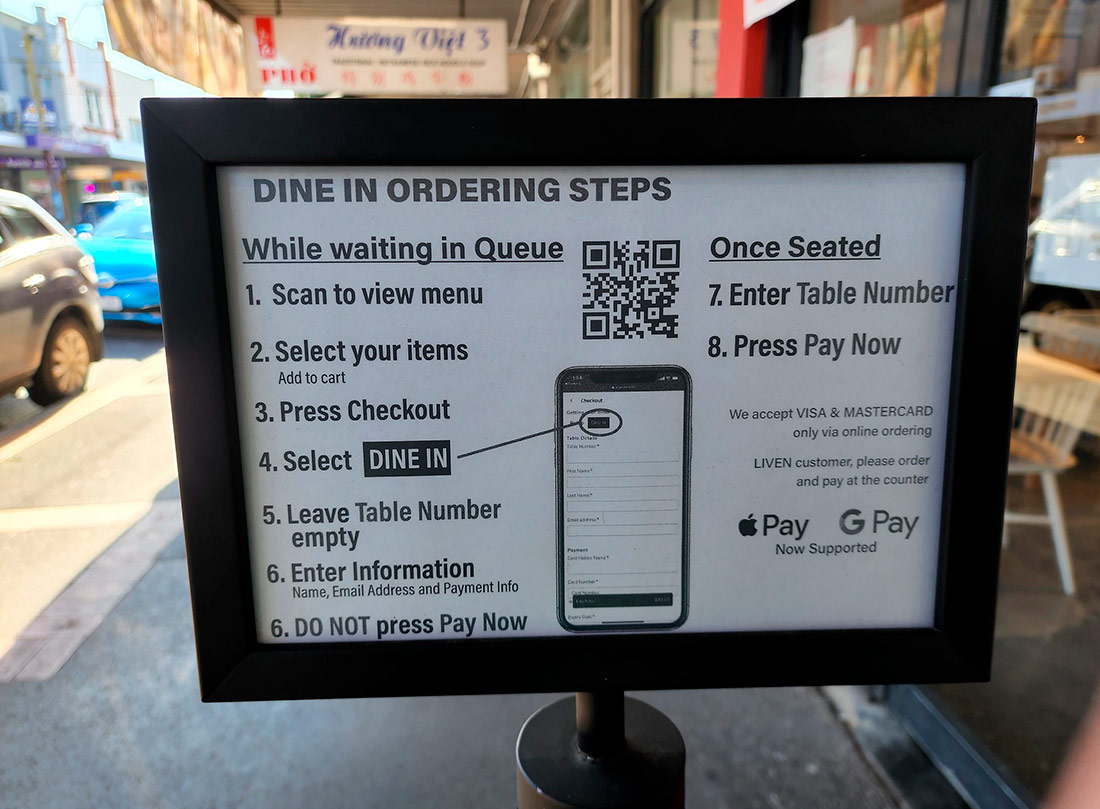

Last week I went to a restaurant. I got together with a group of friends who I hadn’t seen since before the pandemic – there was a new baby, some transoceanic travel involved, and almost all of us had lots of new grey hairs. Like in so many other post-pandemic restaurants, we were invited to browse the menu using a QR code. You know what happens, instead of talking to your friends, looking them in the face or holding the new baby, everyone becomes immersed in the universe of their phone, where someone has tried to squeeze what used to be a menu spread over several A4 sheets of paper onto a mobile screen. The little screen interrupts the flow of communication and the spontaneity of the moment, but it is no longer a novelty. The novelty came at the end. The waiter came over to tell us that we could also pay using the QR code, that we could each pay our own part or split the bill equally, and that it was as easy as making an online purchase. If any of us didn’t know how to make an online purchase, we could call him over. And indeed, he didn’t walk past our table again until the matter of the bill was settled, although the family with the two babies already asleep in their arms had neither the hands nor the will to solve the riddle of the QR code. But, from the point of view of institutions, the problem of the forced digitalisation of society boils down to the personal problem of having the necessary digital skills.

And so we have witnessed the forced digitalisation of society. Citizens are making more use of digital technologies; they use them more regularly and for more tasks. Meanwhile, new products and services have been digitalised that increasingly reinforce digital citizenship. This digital citizenship is essential but unattainable for some sectors of society in certain circumstances, especially for people with fewer digital skills, including many older people.

The pandemic has stepped up the digitalisation of money – in Barcelona, at least, you can no longer pay for a single bus ticket in cash. Doctor’s prescriptions have also been digitalised, and the public health system no longer provides printed prescriptions. Various personal ID systems have become more widespread, such as the personal pin code, the electronic ID card and electronic signatures. The typical museum audio-guide devices are now apps that you have to download onto your phone before searching for the specific audio-guide for the exhibition you’re visiting. And finally, the advance online purchase of tickets for museums, concerts and other cultural events has also become the norm.

Instructions for ordering food in a restaurant | Alpha, Flickr | CC BY-NC

The prevailing techno-optimism only sees the advantages of digitalisation. Restaurants need fewer waiters, bus drivers don’t have to waste time handling money, we cut down on paper for prescriptions and tickets, public workers and cashiers spend less time attending to the public. Museums don’t have to worry about audio-guide devices. But we often fail to see the cost to those who are excluded from these services, the autonomy lost by those who cannot access the service directly, or the impact on the right to equal opportunities and the right to live without discrimination.

Those who are unable or unwilling to exercise digital citizenship are left to rely on the help of family or friends, or are punished by the system with procedures that are more cumbersome than their analogue predecessors. There are those of us who are still quite happy with mobile phones considered by the industry to be obsolete, and we don’t have room for any more audio-guides. If you don’t have space to install the audio-guide on your mobile, you may not be able to access the service. If you don’t purchase online tickets for cultural events in advance, you risk not being able to get one. If you can’t access your medical prescription on the digital health platform, you can ask the pharmacist what you’ve been prescribed, but without having the information written down on paper you may forget essential details that seem important at the time of purchase, such as how often you need to take the medication or the dosage. Although the official statistics say that in Spain 94% of the adult population connects to the internet using mobile devices (Eurostat, 2021), this doesn’t mean that all these people can use all these services, or that they can use them every day, or that they are willing to forego the advantages of analogue services.

There are many reasons why you might be unable or unwilling to access digital services. Lack of digital skills and lack of interest in digital services are certainly among the most common. A lack of skills and interest in digital technologies is often associated with more vulnerable sectors of society with a lower socio-economic status and with fewer opportunities for regular contact with different digital technologies, such as older people who weren’t previously employed or who didn’t need to use computers for their jobs. At the same time, there are young people who are experts in using social media on their mobiles, but who wouldn’t know how to install an electronic signature or what a spreadsheet is. But it could also be the case that you don’t want to access digital services because of digital saturation, with more and more young people defending the right to digital disconnection. Or that you can’t do so because of occasional access restrictions, for example if your mobile phone is broken.

At this point, it is no longer surprising that some of the victims of forced digital citizenship are raising their voices against the prevailing techno-optimism, whether in the private or public sphere, and helping society to reflect on the utopias of digitalisation. It is often older people who show us the limits of the digitalisation of society, not only because some of them don’t have the necessary digital skills, but because they are unwilling to forgo the advantages of the analogue world they have known up until now and which they appreciate for its warmth, versatility and familiarity.

One of the few public cases against the prevailing techno-optimism is the campaign against the depersonalisation of banking initiated by Carlos San Juan on change.org. But in the private sphere, many other older people often take a stand against forced digitalisation. They prefer not to have WhatsApp and not to have to communicate via text messages that people neither write nor read properly, because they prefer a phone call in which you can give and receive all the necessary attention. Then there are those who have given up battling with QR codes and who prefer to have the personal attention of someone who can read out the menu and discuss it with them. Although at the same time they would also probably prefer to be able to continue withdrawing their money in cash and controlling their spending on paper, rather than having to depend on other people who have no business knowing about their finances.

However, little attention is paid to older people who speak out against the prevailing techno-optimism. The ideas of young people who advocate digital disconnection sound out louder than those of older people who complain about the depersonalisation of services, even though both groups are on the same track.

Older people are accused of not knowing how to use digital technologies and of not wanting to modernise, and there is a strong push to incorporate them into the digital society to bridge the digital divide. Yet often, those who are not users of digital technologies, or of certain services, are not only influenced by the digital opportunities they have had over the course of their lives and their digital experience, but their attitudes are also based on conscious and informed choices that question the values at stake with digitalisation.

Older people are often accused of spreading fake news, of perpetuating WhatsApp chains, of not knowing the correct meaning of emojis or of sending useless “Good Morning!” messages. These uses, rather than being a problem of lack of digital skills, are an opportunity to empathise with where the other person is in their life and their emotional needs. However, little attention is paid to them when they call for more face-to-face services, less text messages and more phone calls. In other words, when they call for inclusion, warmth and truly personalised experiences.

Julio | 18 October 2022

Me parece un poco ignorante intentar que personas que no han tenido un contacto tan profundo con las tecnologías las dominen de la misma forma que los nativos digitales, o remotamente similar. Conozco personas que, aún habiendo trabajado con ello, tienen problemas al entender los programas.

Todo ha avanzado muy deprisa. A pesar de que son lo más intuitivos posibles, hay quienes no se enteran, porque están acostumbrados a otros esquemas.

Si quieres ver tus facturas puedes entrar en la app de tu compañía. Si buscas información puedes acceder a la web de cualquier medio. Pero es posible que las herramientas, a pesar de existir la información, no estén suficientemente adaptadas. O ya por el deterioro y la falta de experiencia y comprensión, no puedan adaptarse a las tecnologías y tengan que recibir asistencia presencial.

Leave a comment