Man and woman eating foot-long hotdogs, 1953 | City of Vancouver Archives | CC BY

The intestine and the brain are in continuous dialogue. They collaborate, help each other, and sometimes even harm each other. To do so, they rely on a complex network of communication channels through which they send chemical and electrical messages back and forth. Scientists have been investigating this brain-gut axis for 15 years, and the results are changing the way some mental illnesses are diagnosed, treated and even prevented.

The inhabitants of a small town in Ontario, Canada, couldn’t believe it. What was happening to them – had they been cursed? That May 2000, heavy torrential rains caused wastewater from local farms, full of slurry and high levels of two pathogens, to flood and infect the public water system. As a result, thousands of Walkerton residents fell ill with acute gastroenteritis. Seven of them died and many others began to develop psychological problems. Five years later, one in five residents had developed inflammatory bowel disease, as well as chronic depression and anxiety.

What did that fateful bout of gastroenteritis have to do with the subsequent mental health of the people of Walkerton? Probably a lot, if not everything. We know that people with chronic gastrointestinal diseases such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease are often more likely than healthy people to suffer from anxiety, depression, and mood and emotional disorders. The opposite is also true: people who begin to suffer from psychological disorders eventually develop gastrointestinal problems.

The fact is that the gut and the brain talk to, influence, and help or harm each other. They are in continuous communication, something that, in fact, if we stop to think about it, we have always known, as shown by the fact that our everyday language includes expressions such as “having butterflies in your stomach” or “being shit scared” which clearly reflect this relationship. We also experience it on an almost daily basis, for example when we eat something we like and feel an immense sense of pleasure and wellbeing, or when we feel in a foul mood if our stomach is empty. For many of us, nerves take away our appetite, and stressful situations can lead to intestinal imbalance, whether diarrhoea or constipation.

The gut-brain axis

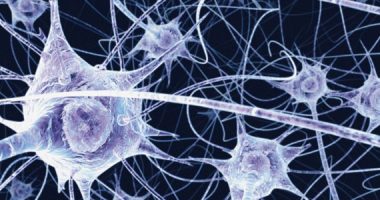

This relationship that we are aware of, albeit unconsciously, was discovered scientifically in the 18th century. For the first time, a French doctor realised that the digestive tract has its own nervous system, the enteric nervous system, which depends on the brain. Three centuries later, in 1996, researcher Michael Gershon, picking up on that French doctor’s idea while doing research at Columbia University in the US, found that the gut is home to hundreds of millions of neurons, many more than those in the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system combined. And he coined the famous concept of the gut being the “second brain”.

These gut neurons found by Gershon secrete important neurotransmitters in charge of regulating mood, such as serotonin, dopamine and GABA; they also allow the gut to perform a range of functions independently. However, unlike those in the brain, gut neurons have no cognitive capacity – they do not generate conscious thoughts, nor are they capable of reasoning or decision-making. For this reason, despite Gershon’s bestseller about this second brain, which has sold millions of copies worldwide, and the fact that it is still a very popular metaphor, the truth is that it is not very accurate.

A communications network

All these gut neurons cannot think, but they can feel. And they send information to their counterparts in the brain, about nutritional needs, but also, for example, about potential pathogens. The brain, in turn, sends the gut requests and questions. All this active exchange of messages takes place via different communication channels. The main one is the vagus nerve, a huge highway that runs between the two organs and transmits electrical impulses through its fibres. It channels a constant traffic of chemicals and hormones that send signals to the brain about the state of the gut while allowing the brain to impact on the intestinal environment. The immune and endocrine systems also collaborate and participate in this exchange of missives, and to a lesser extent, so do the circulatory and lymphatic systems.

At the heart of all this brain-gut communication is the gut microbiota, the collection of more than 39 trillion microorganisms – mostly bacteria – that inhabit the colon, act as a single organ and perform vital functions for human survival, from helping us to digest food and extract energy from it, to manufacturing essential vitamins and training the immune system.

They play a key role in health and wellbeing, although, paradoxically, this role is not fully understood. What is clear is that, if we want to be healthy, we need our microbiota to be healthy, which so far scientists understand as being balanced, resilient and diverse. Alterations or imbalances in its composition are linked to mental health disorders and problems.

The first clue to the close relationship between mind and gut came half a century ago, when experiments on mice showed that any kind of stress, from hunger to sleep, loud noises or separating pups from their mothers, altered the composition of the animals’ gut microbiota, which was linked to an increased risk of health problems. Intestinal bacteria are able to influence levels of serotonin, one of the many biochemical messengers that regulate our mood and behaviour; they promote the metabolism of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with joy, learning and reward; and they are involved in the release of GABA, an essential molecule in modulating behaviour.

Influence on mood

Three subsequent studies have added scientific evidence to this first clue to the brain-gut axis and shown that gut microbiota play a key role in mental health. The first of these experiments was carried out by researchers at McMaster University in Canada, led by Premysl Bercik: they observed that despite eating the same food, the two strains of mice they had in the lab – some calm and shy, the others nervous and aggressive – had different compositions of gut bacteria. They decided to transplant the mice’s faeces between the two groups, and to their surprise, they saw how the animals also swapped characters.

Along these same lines, shortly afterwards and on the other side of the Atlantic, a group of scientists at the University of Cork, led by John Cryan and Ted Dinan, used the same strain of shy mice as in the Canadian experiment and found that they were able to change the animals’ behaviour by giving them a supplement with beneficial bacteria or probiotics: the animals were less anxious and more daring, as if they were taking low doses of antidepressants.

Subsequently, similar studies have also been conducted with humans, trying to discern the relationship between brain and gut and see if it is possible to impact mental health through the microbiota. For example, in an experiment at the University of California, a group of women were given fermented milk twice a day for four weeks and saw positive changes in the areas of the brain responsible for regulating emotions.

The problems begin

While a rich, diverse, balanced and resilient microbiota is often associated with improved emotional wellbeing, imbalances in its composition have been linked not only to mental illnesses and disorders, such as anxiety and depression, but also autism and even Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis. However, it must be said that this is still a very new field of research, going back only 15 years, and that for the time being, we have many clues but limited knowledge.

What we do know is that one common denominator in many of these neurodegenerative diseases and mental disorders is that sufferers tend to have an altered microbiota and therefore gastrointestinal problems. It has also been shown that treating gastrointestinal symptoms can improve the symptoms of neurological disease. Moreover, studies have found that by transferring bacteria from children with autism spectrum disorder to healthy mice, the animals developed symptoms similar to those of the children, such as social aversion.

Many gut microorganisms are capable of secreting inflammatory substances that can escape from the gut and travel around the whole body through the blood. And chronic inflammation is known to contribute, among other things, to the development of Alzheimer’s disease. What is more, many of the genes involved in Alzheimer’s disease are also associated with inflammation.

The next revolution: psychobiotics

A growing body of work suggests that the microbiota influences the way we cope with life, so the healthier this community is, the more positive its influence will be on our emotional health. The main factor influencing gut microbiota is diet, so researchers are already focusing on what foods might modulate the gut bacterial community to impact on brain health.

Some are even investigating cocktails of beneficial bacteria capable of producing neuroactive substances, such as GABA or serotonin, which act on the gut-brain axis to reduce anxiety and sadness. These are the so-called “psychobiotics”. Perhaps, in the not-too-distant future, we will be able to use these combinations of bacteria to lift our spirits. Although it’s a bit unsettling to know that an association of bacteria, from a dark corner of the gut, controls our brains and our moods… don’t you think?

Maria | 13 November 2022

Todo lo q dicen sobre los estudios recientes es asi, porpq lo vivi con mis intestinos inflamados y hasta en el cerebro sdntia ondas energeticas muy invasiva y comwnce a dejar todo lo refinado y consunir de a poco fermentados chucrut kefir y hacer ejercicios porq sabia q esos flash q me hacían percibir q me estaba volviendo loca pero duraba nada la confusión sobre mi estado mental y la luche y cada vez encontraba mas info sobre como el intestino es el 2do cerebro y gracias a tanta info que hay y a los tes como de canela, orégano ajo y todas las verduras y todo lo q nace naturalmente de la tierra y mata las bacterias malas y hongos..

Carlos | 14 November 2022

Gran artículo

Leave a comment