Sensorama | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA

Immersive technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality have matured to a surprising degree over the last few years. We are leaving behind the so-called ”wow effect” as we move towards a new era in which content will reign supreme. We need narrators who can understand future needs and put together a new language for this narrative format. A blend between film and video games, but with its own very distinct rules, where immersion, interaction and empathy become the driving forces between all these stories.

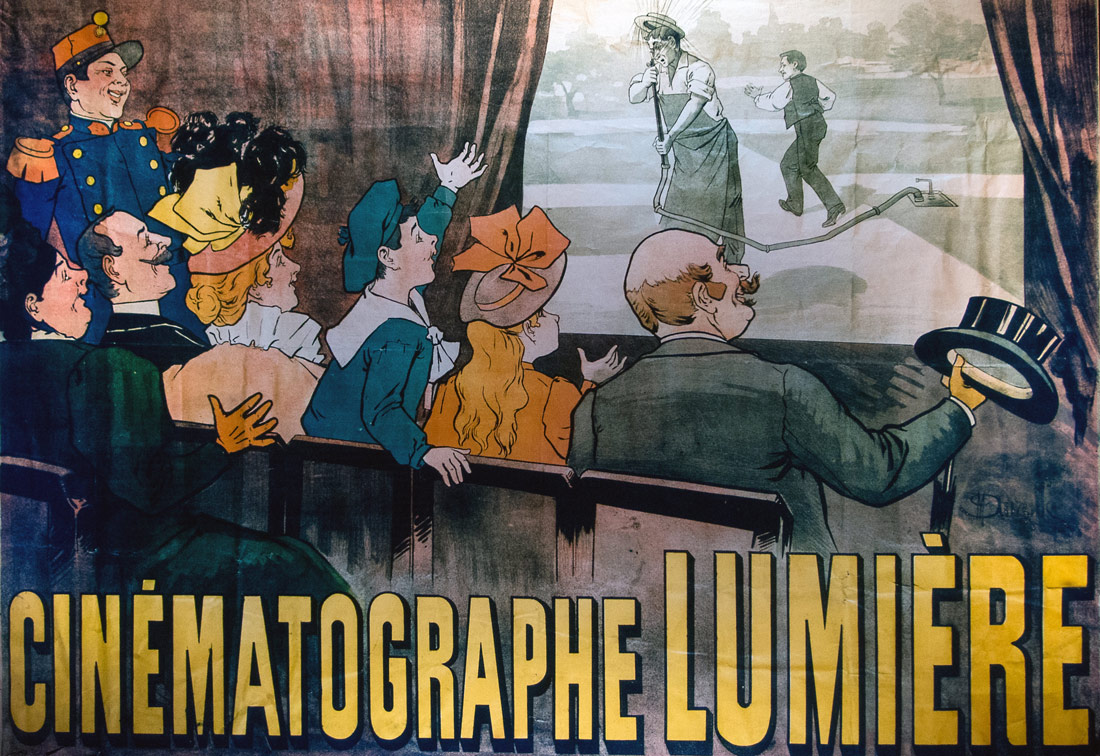

After film was born, how long did it take to reach narrative maturity? Some might think we still haven’t reached the peak of creativity, while others will say that the sun of cinematic imagination already set some time ago and there is no more room for innovation. However, more or less pessimistic forecasts aside, there are undeniable differences between the first productions of the Lumière brothers or Georges Méliès and, for example, the work of Stanley Kubrick.

Because in the beginning it was all pyrotechnics and experimentation with the medium, to produce the well-known ”wow effect” among amazed audiences who were experiencing film for the first time. But over the years, surprise ceased to be the main reaction and stories came into their own. It was no longer a question exclusively of how, but also what. We could almost say there existed a cinema before cinema; a kind of proto-cinema which, lacking the full characteristics of what this art would turn into, was an essential starting point that paved the way for what was to come. A period of experimentation that, to draw a parallel with the current day, is now occurring with virtual reality. (Not to mention with augmented and mixed realities as well).

Screenshot from Le Voyage dans la lune, 1902 | Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain

This is how George R. R. Martin defined it a few days ago in relation to the 360º video content of Nightflyers, an adaptation of the science fiction novel he published in 1980. The author of A Song of Ice and Fire (did anyone say Game of Thrones?) considers that the technology has matured, but that we still haven’t been capable of imagining what we could do with it. Even if you don’t agree with his assertion that in twenty or thirty years’ time virtual reality will replace film and television (our view is that it will complement rather than replace them), he certainly hit the nail on the head when he said we’re currently in the period of theatre before Shakespeare.

The interesting thing about all this is that immersive fiction experiences are created from a mixture of film narrative and video game narrative, with certain connatural limitations to the new format. Anyone filming a 360º video will know that it’s impossible to continue thinking about shots in the same way as footage created for the big screen. Then there’s the interaction that’s characteristic of virtual reality, very similar to that of video games, which – if present – should make us wonder whether we’re in a film or a game. Or perhaps the lines become blurred, like when it comes to defining the nature of a novel?

The fact is that there are many immersive experiences, of many types. From those that simply offer a 180º or 360º video to the most complex CGI creations that allow us to move and touch everything we encounter. All are potential stories that try to draw us in by deploying the characteristic resources of this medium. And many of the great narrators from other formats are beginning to take an interest. Take filmmakers, for example. We have Robert Rodríguez, with The Limit – his tentative excursion into the medium. Tentative because he created this film in the traditional manner before later transforming it into a kind of immersive experience in the post-production studio. Or Darren Aronofsky in collaboration with the creator Eliza McNitt, who came up with a series by the name of Spheres. Even David Lynch has played around with the much-loved Twin Peaks and new technologies. And even though it’s not within the sphere of cinema, we mustn’t forget the work of Björk, that master of artistic innovation, with some immersive creations that are pure art.

Cinématographe Lumière | LibreShot | Public Domain

However, much practice is required. Much trial and error. We need creations to keep emerging that inspire others to create. Ideas that pave the way to other, more refined ideas that come closer to representing the maturity of the medium. A maturity that, as far as possible, should be reflected in one or several of the following points:

- Virtual reality becomes almost meaningless if we leave out the sensation of maximum immersion in the virtual setting. Something as simple as getting into a car next to the characters in Pearl can be just as exciting as the story itself.

- One of the great difficulties of this new medium comes from the intersection between the worlds of film and video games. If there’s a lot of interaction, does it cease to be a film? And if we don’t interact, what new experience does it offer us? While we’re trying to resolve this conundrum, the possibility of narrative pieces that, like video games, change their endings depending on our decisions, might not be a bad idea.

- The “empathy machine” – this is the moniker given to virtual reality. A unique technology when it comes to putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes. As immersive as it gets when we see – and feel ourselves – in another place and another body. We can even start to think for a while like the character we take on. Raw, unfiltered emotion – for good or for bad. If we feel uncomfortable seeing someone cry in front of us in real life, the same thing will happen in a virtual reality setting.

- Exploring new limits. We’re currently crossing over the boundaries of previous formats, but new limits will be created that will, in turn, be exceeded by the most ground-breaking authors. Pieces like Zero Days VR are a mixture of between documentary and fiction that skilfully exploit many of the resources offered by virtual reality.

The technology is already here. Anyone who has tried the latest immersive experiences will have noticed the significant qualitative leap from the games and films being produced just a few short years ago. And now it’s time to develop the content. The time for new narrators, who will be capable of taking a language that is currently emerging and using it with confidence. People who will move effortlessly between the media of film, series and video games, and who will know how to exploit the possibilities of added value offered by immersive narrative experiences. New Shakespeares for new types of theatre. A theatre the likes of which we have never seen – or experienced – before.

Elliana Murray | 17 May 2023

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

Leave a comment