Demonstration of Assemblea d’Actors i Directors de Barcelona on the Rambles, 1976 | © Pilar Aymerich | Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques. Institut del Teatre.

The Grec theatre festival of Barcelona has its origins in a cultural self-management experience undertaken by performing arts professionals. The years 1976 and 1977 are the two years of this forgotten experiment that we are recovering here. The self-management, political change, counter-culture and underground currents of history also enable us to reflect on self-management and culture today.

“Theatre professionals find themselves forced to undertake management tasks in this Hellenic enterprise that, above all, has a theatrical and a democratic direction. Rather, it should be said that by sticking up posters and selling beers, the actors and directors are showing their high level of professionalism. Sometimes selling beers can be an act that is as artistic as it is necessary.”

This was a scenario from the first Festival Grec in the words of critic and playwright Jaume Melendres speaking to Tele/express. This is how the summer festival of Barcelona par excellence was founded: self-managed, egalitarian and ground-breaking.

It was in the year 1976 when need, combined with a transformative cultural force, led actors and directors from Barcelona to create the Festival Grec. With the recent death of Franco, Barcelona was a human, political and cultural pressure cooker. Collective culture was managed by performing arts professionals without any support from the Francoist city council under Joaquim Viola. This article aims to explain two years of the self-managed Grec and all the political and cultural upheaval of the time.

Counter-cultural upheaval

Franco’s death opened doors, despite the fact that the regime wanted to die by killing. These were uncertain and ambiguous times when the accumulated repression, in private and public life alike, spurred young people to take to the streets. Pau Malvido, a counter-cultural poet who was a witness and protagonist of the era, explains to us that they were a mixture of children of the working class, of the petit bourgeoisie, of immigrants, neighbourhood kids, left-wing students, sui generis hippies, high-class snobs seeking intense emotions and all kinds of misguided city fauna. This working-class, hippie, geeky and unclassifiable youth had little to do with flower power, and could not forget “the accumulated ill-feeling and the left-wing and skid-row origins of the subject.” Malvido talks to us about a modern drunkenness. “Insolence” became an everyday political weapon:

The current political picture above all is about signing up for something, about saying this mouth is mine, about saying “we want this, we want that”. And there are people who are more into saying “I do this, I do that and what’s the problem, eh?” Modern drunkenness is this insolence that is starting to be seen, this message at the time of doing things however one feels like doing them.

As Malvido explains, self-management and the end of a prophetic policy emerge at that point.

Evidently not all politics moved around these counter-cultural circuits. There was “el Partit”, the PSUC and the Assembly of Catalonia trying to join in any demonstrations against the regime in their space. In counter-position were the Trotskyist and Maoist parties. Furthermore, anti-authoritarian groups with links with the CNT where counter-culture, self-management and anarchy were forging paths, not without their tensions.

Historian German Labrador in his valuable work “Culpables por la literatura” talks to us about the sensation at that time of wanting “to have many lives”. Beyond work and the productive facet, the penumbra of the political situation shed light on other ways of living. In this sense creativity (literature, art and theatre) were a natural tool for fighting and experimenting.

Theatre, liberty and watermelons

The spring of 1976 saw the creation of the Assemblea d’Actors i Directors de Barcelona (Assembly of Actors and directors of Barcelona – AAD) with the aim of equipping workers with a horizontal trade union, promoting theatre and spreading the idea that this was a public service. The Assembly came from a year of trade-union struggles with a state-wide actors’ strike in 1975 protesting against the endemic precarity of the sector. Director and actor Mario Gas, a member of the Assembly’s committee, explains to us how collective agreements were negotiated, an attempt was made at creating a municipal theatre, and finally a proposal emerged from some members that involved grouping the profession not in a theoretical manner but from the praxis of our work, which was theatre”. This group was responsible for pressing ahead with the first two editions of the Grec Festival, in 1976 and 1977. A festival that recovered a municipal facility, the Grec theatre on Montjuïc, which at that point had been closed for two years.

Show “Plou i fa sol” by Comediants. Teatre Grec, 1976 | © Arxiu Comediants

Mario Gas explains to us what self-management consisted of:

We thought at that time that there was an obsolete and collapsed business sector and that no strong public sector yet existed and so we pressed ahead with self-management. What did it consist of? At the AAD, trade union representatives and members of the committee managed to get money from the ministry in Madrid and the people close to Barcelona City Council. And with all that we made equal wages for everyone.

The first edition was a massive success. It started on 1 July with a demonstration on the Rambles under the slogan “Teatre Grec 76, Popular Season. For a theatre at the service of the people. Theatre and liberty. For an imaginative theatre”. The text of the programme was by Manuel de Pedrolo and all kinds of theatre were shown with almost 100% of the sector working on those days as well as the legendary seven hours of rock with performances by Sisa, Pau Riba and Oriol Tramvia. There were also performances by singer songwriters such as Lluís Llach and Maria del Mar Bonet or Portuguese singer Zeca Alfonso, author of ‘Grândola, Vila Morena’. Finally, and among many other activities, there was also space for dance with the National Ballet Company of Cuba.

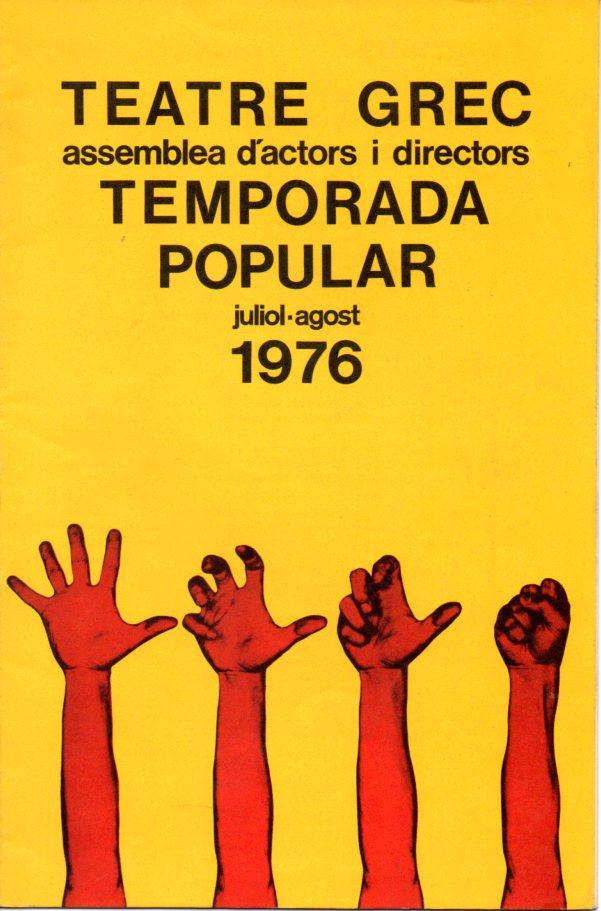

Poster of Teatre Grec 1976. Assemblea d’actors i directors. Temporada popular | Unknown author | © Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques. Institut del Teatre.

In the chronicle of the Grec written by Carlos González we find a criticism by Altirriba in the Dominical del Brusi. It tells us of how at that Grec a change in theatre took place in a text titled “The watermelon defeated the cushion”:

The success of the watermelon on the first day – twenty-eight were handed out – and the failure of the cushions – only five were hired – represent, for some, the start-up of a new cultural policy and, for the more sceptical, a qualitative change of audience, a form of snobbery.

At the first Grec there was no shortage of arrests or of police. The so-called “social” appeared in order to confiscate censored issues of the magazine Ajoblanco and arrested four of the organisers who were released the following day.

Split

The Festival had been a categorical success on a theatre level and a political level alike. But the internal tensions between different sectors led that expression of self-management and freedom to explode. This is illustrated by the words of Gas:

After the Grec had finished, adhesion to the Assembly of Catalonia was proposed. A year later this was dissolved by the very same members. One sector, to the very far left, said that it was leaving in the light of this and we tried to avoid a separation occurring. We wanted to be a consolidated progressive force but without signing things that would lead to the dissolution of the Assembly. (…) By a very small margin it was not to be, and this led to the split between the assembly which ended up with the name, of a more institutionalist nature, and the Assembly of Performing Arts Workers (Assemblea de Treballadors de l’Espectacle – ADTE), of a more libertarian and anarcho-syndicalist nature.

Gas, who joined the ADTE, explains to us regarding this organisation:

We were from different ideological tendencies but what we shared was the desire to break witheveryhing, and the idea of seeking new associative, ideological and artistic routes. From there we organised El Tenorio del Born, on New Year’s eve at the Poble Espanyol, we collaborated with the libertarian conferences of 1977 in the Park Güell and we kept the Saló Diana on Carrer Sant Pau open for 18 months.

The ADTE followed a pathway of experimentation, transgression and successful self-management but also with difficulties of all kinds, leaving as references the performance of an eclectic Don Juan Tenorio at an occupied Mercat del Born and the activity of the Saló Diana.

Show “Don Juan” at Mercat del Born, november 1976 | © Colita | Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques. Institut del Teatre.

According to the critics, the 1977 edition, organised by what remained of the AAD, did not have the same power as the first edition. Even so, Grec 77 featured the American company Bread and Puppet Theatre, as well as recovering plays by Miguel Hernández and Salvador Espriu and including a performance by Ovidi Montllor. In the working magazine of the PSUC, the critics team “Cul d’olla 2” valued thus the failure of the edition:

It was in the mood of a large part of the target audience the fact that the current management did not have any of the unitary or self-management sense that the previous campaign did. Also, the lack of unity among members of the profession itself that was at the head of the committee responsible often appeared during the activities of Grec 77. (…) A negative balance not only in the economic aspect but also in the field of the experience, the work, the management, and the closing of the gap between the people and the theatre. And that is what is really serious.

The Assembly was finally definitively dissolved and in the summer of 1978 there was no Grec Festival in Barcelona. In 1979, now with the democratic city council, the Grec returned, this time with public management by the socialist city council. Self-management disappeared from the map and the cultural sector adapted for better or for worse to the new institutionalised policy. It is important to remember also that there were many people who took part in that frenetic cultural and counter-cultural explosion who would not stand up to the change: some would be marginalised, others would give in and still others would disappear, and unfortunately some would also die.

Self-management today

But how can this experience help us today? At the current point in time Barcelona is saturated with shows and with culture. Tackling this is impossible and often the quantity blurs the value of the quality. With quality, beyond its excellence, I am referring above all to the sense of that show performance, of the affects generated in its environment, of the networks that it activates, of the impact it makes on the city and of the people beyond its business turnover. Reviewing the origins of the Grec and the Barcelona of the 1970s does not aim to be an exercise in nostalgia but a historical mirror for thinking about the present.

Would a festival like this in Barcelona be possible today? In all likelihood an equal experience would not be possible. In 1976, people were living an explosive political era, with risks and possibilities. Cultural workers were capable of organising themselves into trade unions. Moreover, we are currently living in strange times – censorship has been revived – where more than ever we need cultural artefacts of this type: empowering, subversive and radical. But we live in a context directly opposed to that of 1976: the democratic project was setting out with severe weakness and with the arrivals of the structural crises the state has shown its most punitive and arbitrary face. Culture has also changed: show business and capital are invading everything, including each of our own vital facets. New technologies have transformed culture, inundating our lives with experiences for never-ending consumption but at the same leaving the workers devoted to it in a precarious situation.

And, despite this pessimistic portrait, counter-culture, self-management and self-organisation are still surviving outside the major performing arts businesses in the city. It might even be said that they are being revived despite being little known and still isolated realities: Experiences such as that of the SMAC! Musicians’ syndicate provide an example of self-organisation. Also the self-managed fairs of fanzines such as FLIA, Gutter Fest and Graf or the irrepressible independent alternative venues such as Freedonia and Hi Jauh USB. Or the veteran Ateneu de 9 Barris and El Lokal in the Raval, among many others.

The reason behind this survival is difficult to explain. It is the desire to rebel and to express oneself that manages to take these underground currents forward against the grain of everyday life and the establishment. There is no path to be followed; only a poster by Espai en Blanc on the wall that blocks the way forwards encourages us to jump: “The best fight is the one fought without hope”.

González, Carlos (2001). «25 anys de Festival: 1976 -2001». Barcelona: Arxiu Grec – Ajuntament de Barcelona. http://lameva.barcelona.cat/grec/arxiugrec/en/25-years-festival-1976-2001-carlos-gonzalez

Labrador, Germán (2017), Culpables por la literatura. Imaginación política y contracultura en la transición española (1968-1986). Madrid: Akal.

Malvido, Pau (2004). Nosotros los malditos. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Nazario (2016). La vida cotidiana del dibujante underground. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Ribas, Pepe (2011). Los 70 a destajo. Ajoblanco y libertad. Barcelona: Destino.

Vilarós, Teresa M. (1998). El mono del desencanto. Una crítica cultural de la transición española 1973-1993. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

Pere Pedrals | 05 July 2018

Si no m’erro, el cartell del Grec 76 és del Iago Pericot.

Salut.

Administrador | 06 July 2018

Gràcies! ho comprovem i si cal esmenem!

Moltes gràcies!

Leave a comment