Baseball match, Rosetta High School (Australia). Source: Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

We can currently approach the concept of gamification from many different angles. The material published on this phenomenon offers a range of interesting ideas, but we have to take care and ensure that it isn’t used as an empty concept. A user-centred definition allows us to set out game-creation guidelines based on the player as the constant. Then we must create a narrative that envelops players in the game, following a path marked out by rules and challenges in a non-game context. Gamification is not measured in terms of the prizes and badges awarded or received, but by the player’s enjoyment during the process. There is also room for gamification in the world of culture. The idea is to create a story that goes beyond the physical premises of the cultural centre and that adequately gauges the relationship between players and the sensitive material that they play with.

Certain words and concepts become fashionable at particular moments in time. A few years ago ‘knowledge management’ and ’emotional intelligence’ were in vogue, and their importance is beyond doubt. Now, ‘gamification’ is in, and those of us who have been using games as a tool in our work for years are suddenly snowed under.

The literature on the subject is growing steadily. Numerous conferences, books, websites and articles analyse many fascinating related aspects from different points of view. But one thing worries me: gamification is often used as an empty concept, as a series of formulas that anybody can apply. Many people think that gamification means awarding points or badges, or creating lists or rankings. So it’s quite common to come across projects that think gamifying means doing ‘exactly the same as before, but allowing players to earn points.’ You can see the consequences of this misunderstanding if you enter the word ‘gamification’ into a search engine: the results show images of badges, fictitious prizes or infographics explaining what it takes to win the badges or prizes.

The problem lies in the definition itself. In his Gamification. How Game Thinking can Revolutionise Your Business, Kevin Werbach [1], one of the most influential figures in the gamification world, describes it as ‘the use of game elements and game-design techniques in non-game contexts.’ Further on he explains that the aim is to make users commit to an organisation or a cause, or to motivate them to take a particular action, allowing them to experiment without fear of making mistakes.

Another recurring element in the literature on the subject is the attempt to distinguish between gamification and games. The idea is to use game mechanics to create something that is not a game. This definition reminds me of a scene from Catalan TV series Plats bruts in which the protagonist, David, decides to read James Joyce’s Ulysses. First, he sets the mood: sofa, light, classical music, a cup of coffee. When everything is ready and he is about to start reading, he calls to his maid to come and read to him. David has set up the mechanics of reading, but without the actual reading.

A user-centred definition

Given that gamification aims to motivate somebody to behave in a particular way or to carry out a series of specific actions, this user should be at the centre of the definition and of the thought-process that the designers use to create a gamified action. So I’ve allowed myself the luxury of re-writing the definition from a different perspective, and then looking at the consequences of this change.

Gamifying means providing game experiences in non-game contexts.

This definition may initially seem very similar to Werbach’s, but placing the user’s experience in the centre has significant consequences. I will explain what I mean by focusing on what I consider the three most important concepts. The order is not important, they are all on the same level, but all three are deeply interconnected and I don’t think you can understand any one of them without the other two.

Do you want 2 play a little game? Source: Carl Jones.

First concept: offer experiences

The centre of any gamified activity is the user. We have to do everything within our power to design a rich experience, a motivating challenge. To do this, we need to know who our target users are, and create a profile specifying the kinds of challenges that motivate them.

This approach has three consequences. Firstly, given that there are different types of players [2], designers have to ensure that the activity provides different challenges for each of them. This means mapping out all the possible challenges that come up during the activity, and cross-referencing them against the different types of players.

The second consequence is that players must always be able to remain in the activity, which means deigning feedback mechanisms that allow players to re-join or exit through the activity [3].

This infographic by Daniel Solis illustrates the two types of feedback.

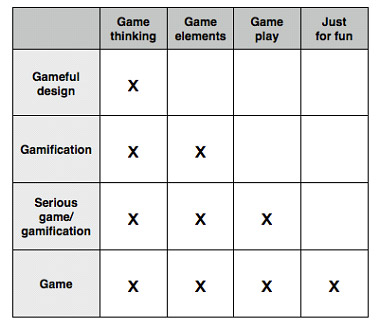

And the third consequence is that it contradicts a standard classification of different game experiences that Andrzej Marczewski explains in his book Gamification: A Simple Introduction. In this framework there is no difference between gamification, ‘serious game’ and game, given that they all centre on the experience of a user who is faced with a challenge. The only difference is the importance given to the game aspect: in games that are just for fun, the subject matter is only important in terms of the story. In the other two cases, the subject matter is one of the three main pillars of the activity.

At the same time, many of the gamified activities discussed are simply activities that are designed around play, but don’t have a real game structure. And the game structure cannot be defined externally, only the person playing can define it.

When users are placed at the centre of an activity, gamification, ‘serious game’ and game end up merging into a single concept. And many gamifications end up being shifted to the category of gameful design.

Second concept: game experiences

Another classic definition of gamification is the use of game mechanics to ensure that players have an interesting experience. Issue 10 of Control Magazine International presents 38 game mechanics that appear in very popular videogames. A quick overview reveals that these mechanics alone are not enough: we can identify games that share the same mechanics but were so boring they fell out of our hands.

In the chapter ‘The Game is Not the Rules’ from the Kobold Guide to Board Game Design, board game designer James Ernest, points out that the rules are not the fun. And to really drive the point home, he includes rules as part of an indivisible system made up of numerous elements that ensure a player finds challenges, fun, and immersion in a world intended to be enjoyed.

A game, Ernest argues, should be conceived as a system based on a structure that engages the player from the start with an immersive storyline, that has well-structured rules to ensure that all the players have opportunities to master the challenges at all times, relevant mechanics that allow everybody to express their interest at all times, and an aesthetic that seeks to ensure that players enjoys every moment of the process [4]. An in order to achieve this, talent and know-how are not enough: there must be a process of testing and modification in order to find the right balance for all types of players [5].

So providing a game experience goes way beyond simply awarding points, prizes or badges, or ranking players. It requires working on the very heart of an activity and guiding all the elements so that they all point in the same direction. And the underlying aim should be to allow users to join in freely, to give them one or more challenges to overcome, and a set of rules to follow in order to do so. After all, this was the objective of a gamified activity. If we simply offer a handful of prizes, players will only remain engaged for as long as the prizes interest them. If the entire system is geared towards this objective however, users will participate regardless of whether or not there are prizes.

For this reason, the creator of a gamified activity will have to put a lot of thought into answering the question ‘how can I manage to make the user actively participate in the activity in question?’

Third concept: in a non-game context

As we mentioned earlier, in order to design a gamified activity we must take the content into account. We have to remember that it is’ a game with a subject matter’. So it seems clear that step one is to specify the subject matter.

Then, we have to carefully decide our objectives. An objective is an arrow that points in one direction or another. A change of direction, no matter how small, will lead to a totally different point of arrival.

Once we have our objective, it is time to think about the user and decide which types of game mechanics will best allow him to reach this objective. This means that the designer of the activity must be familiar with a wide repertory of game mechanics and know how to combine them.

Then comes everything else: the story that wraps everything together, the dynamics that arise between the players, the way we make users enter the world we’ve created and, most importantly, the tests to ensure that we’ve succeeded in our aim.

On the way, we will be tempted by the idea of offering prizes. They seem to be a good solution when we are stuck on a particular problem. But they are just a mirage, because a well-designed game doesn’t need badges: the activity is a reward in itself. We know that we have gamified successfully when we manage to engage users in the activity for its own sake, not for what they can get out of it.

So how do we go about gamifying culture?

Gamification can extend to all areas of knowledge or life. Cultural facilities can also create gamified activities to focus users’ attention on a particular discourse or a series of pieces that they want to highlight.

If we want to bring about a profound change in visitors we must aim high, a small gesture is not enough. We want users to commit for the long haul, to have an experience that goes beyond the walls of the cultural centre and that spreads by word of mouth, as an experience worth sharing.

This ambition goes hand in hand with a personal commitment to do something different. The creator of a gamified activity needs to have a broad vision, and must constantly add new resources, mechanics or ideas that can be used in the creative process. Therefore, we have to start by digging out familiar mechanisms such as the escape valve to lower the pressure of the blank page.

The way users enter an activity is important. One way to immerse users in the world we are creating is to generate a narrative layer of the cultural centre, the works on display, or the tour. It doesn’t need to be a profound story, it can be a small gesture or an interesting challenge.

And lastly, as with any activity, we have to imagine that users, regardless of their age, can go home after visiting the centre and explain what they have done in a short sentence. That sentence is the essence of our objective. It must express what we would like them to have experienced, and what we want them to remember.

There are not many interesting examples of the use of this gamified approach. Gamified activities at cultural facilities are often very brief, and they sometimes end up using the game as mere entertainment, without going deeper into the concept that is the real objective of the activity

In Find the future, Jane McGonigal creates an activity based on the challenge of writing a unique book inspired by 100 works from New York Public Library. To do so, users must first overcome challenges and solve interesting enigmas. The High society exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London included a small and very interesting videogame in which players overcame challenges while becoming familiar with the tea and opium trade on the Pearl River Delta. The game was the gateway that led the more curious visitors to understand what the exhibition was about.

Closer to home, we recently created two challenges for teenagers and adults at the Born Centre Cultura de Barcelona. La ciutat amagada is an activity that takes place twice a year, in which users are led through a historic event and are asked to discover the author of a particular deed by solving puzzles, analysing the archaeological site at the Born, and experiencing the story in the form of a three-screen video game.

All the elements of gamification were used to create it. The starting point was a narrative based on a historic event (the story of who killed Prince George and the creation of a conspiracy to prevent a treaty between England and the Catalans). Once we had the story, we chose historical characters and studied their life stories, and invented a series of engravings, texts and clues that helped to solve the case. Then we had to find game mechanics that worked: each story is divided into three episodes, each containing a specific challenge with a clear question. Once the time to solve it expires, players receive a historical explanation that contextualises the events in order to ensure that everybody can follow the plot.

The solution to each puzzle is a personal challenge, so we included two envelopes with the answers that the players are free to look at if they feel stuck.

We know that the game works because nobody has ever wanted to check those answers, because there is no need for winners. Everybody who meets the challenge feels rewarded. On the other hand, we know that it fulfils its mission in a cultural facility because it allows users to discover its history. Because the educator follows the narrative thread, and, at the end, helps users to distinguish between reality and fiction. And the fact that the story is divided into three section helps to ensure that players remain hooked at all times: if somebody loses their place, they can join again when a new block starts, with the same opportunities as the others.

By way of conclusion

Culture is one of the unmet challenges for gamification specialists. The idea is to create games without forgetting that we are working with sensitive material that users should be able to recognise and adopt as their own. It is no easy task, but when the user is placed at the centre and the designers have sufficient game resources, it is possible to achieve experiences that extend beyond the cultural centre in which the activity takes place. This is the challenge, a game in itself.

[1] Werbach runs one of the most important current MOCCs on the subject of gamification. Rita Barrachina offers an in-depth analysis of this course (in Catalan) on her blog gamifi.cat.

[2] In this blog post blog post, gamification expert Yu-kai Chou sets out different categories of players.

[3]Feedback is the mechanism by which the game is modified according to the player’s results: if it is too easy, the game gets more difficult. If it is too complicated, the player is given some advantage that allows him to get back into the game. For more information see this article by Ernest Adams.

[4] A very interesting article along these lines is MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research by Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc and Robert Zubek.

[5] A well-balanced game means that players never lose interest at any point. You can learn a lot about this concept in The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell or in this article.

Flavio Escribano | 16 May 2014

Estimado Oriol,

gracias por este alternativo y refrescante punto de vista sobre la gamificación.

Coincido en en esta aproximación en muchísimos puntos, y ha sido para mí una satisfacción encontrar pensamientos como por ejemplo: “En el camino existe la tentación de los premios. Son una buena vía de escape cuando no se sabe cómo resolver un problema determinado. Pero solo son un espejismo, porque una actividad bien diseñada no necesita ninguna medalla, la actividad ya es un premio en sí misma.”

No menos sorprendente y esclarecedor que los jugadores de “La ciudad escondida” decidan deliberadamente NO abrir los sobres de “ayuda”

Por otro lado te dejo algunas reflexiones:

1. Como seguramente muchas veces has incorporado en tu teorización del juego, el uso de la “narrativa” es algo supletorio, es por ello que quizá -sobre todo al inicio de tu artículo- sustituiría “narrativa” por “trayectoria” o -como usas más adelante- “recorrido”.

2. Hay algo que nadie se molesta explicar en teoría de la Gamification. Qué o cuáles son los contextos no-lúdicos. Para mí no existen estos contextos no lúdicos, constantemente estamos generando Magic-Circles

3. Por otro lado tampoco creo que el juego sea NUNCA “just for fun”. Siempre hay un propósito detrás de cada juego (se monetice o no dicho propósito). Jugar es una necesidad, no una opción.

Muchas gracias de antemano, por el artículo y compartir estas interesantes ideas.

Oriol Ripoll | 17 May 2014

Oh! Gracias por las reflexiones. La voy a re-reflexionar:

– Podemos entender el juego sin narrativa, pero si la queremos incorporar no puede ser un “parche”, simplemente un tema en el que no juega un papel importante en el desarrollo de la dinámica de juego. Para mí, narrativa es una cosa, recorrido o trayectoria otra muy diferente.

– Exacto. Podemos crear un contexto lúdico donde sea. Pero tradicionalmente, una reunión para desarrollar un tema determinado o una exposición eran temas “no lúdicos” (sólo hay que ver cómo están pensados algunos museos para entender claramente qué significa “no lúdico”:-)

– Creo que el único que puede determinar el uso del juego és el jugador. Tres jugadores pueden estar jugando a lo mismo y uno hacerlo “just for fun” y los otros dos intentando desarrollar una capacidad. Aquí el error está en mezclar “el objeto juego” y la experiencia de juego.

Toc! Te paso la pelota! 😉

X Chicote | 01 June 2021

Un artículo interesantísimo. Estoy diseñando un videojuego para mi TFM para aplicar en la asignatura de FOL para enseñar los contratos de trabajo y sus características y no dejo de dudar entre la gamificación y el aprendizaje basado en juegos o los juegos serios. Creo que en la práctica hay muchas veces que la línea que diferencia estas metodologías es bastante difusa, pero tu artículo sin duda me ha dejado claro lo que engloba el término gamificar… Sin duda realmente bien explicado, además de que su utilización en el mundo de la cultura (siempre tan olvidado y tan teorizado) me parece imprescindible.

Un saludo.

Leave a comment