School children reading the “Our New Friend” book. (simpleinsomnia). CC-BY.

The idea of preventing internet access for minors is utopian and discriminatory. Leaving them to explore on their own is dangerous. We need to find ways to help them be online in a way that maximises their opportunities and minimises the dangers. But where do we start? What tools can help us achieve this aim? How do we approach the problem if we are not comfortable with social media ourselves? The good news is that this is a common problem, so there are useful, accessible resources to help us to start talking about our concerns, provide support, or at least offer some basic coordinates to start from. This post aims to offer an overview, but please note: it is not an exhaustive compilation of all available resources, and it is not written from the perspective of cybercrime and cybersafety.

Educating children on the use of the internet and social media is similar to teaching them when and what to watch on TV, or how to behave in the schoolyard, or on public transport. Nonetheless, certain factors that are specific to the digital environment make managing identity and privacy a complex but essential task. From the first time children or teenagers go online, they need to understand that the internet is a field with no gates and no gate-keepers. And, ideally, they should connect in the company of adults who can guide them in the critical, safe use of the net.

Increasingly, parents, teachers, and other agents involved in the education of young people are expressing concern about the risks of using the internet, especially social media. Although the challenge is new, the solutions are based on common sense: accompaniment, using the internet as a family, and dialogue are necessary (but not sufficient) strategies to teach children how to manage their online identity while protecting their privacy.

Indeed, both digital natives and digital immigrants need to understand the game rules, the limits, and the opportunities and risks that go hand in hand with this new, unparalleled scenario. What makes it different is the fact that although it is new for young and old alike, young people tend to explore it with greater ease and skill. This reverses the traditional dynamics of who teaches who. However, we should not equate knowing how to click or carry out efficient searches with being aware of the consequences of our actions on the internet. Digital literacy must go beyond simple skills, and encompass understanding. In this sense, co-use is key. And co-use can also mean learning together: this way you lose your fear of knowing less than your children do, your fear of feeling lost. You shouldn’t forget the saying that wisdom comes with age, and that you will always have the added value of experience acquired in different scenarios (even if they are not digital) to help you discern and judge in a way that children cannot. Children and teenagers (digital natives) relate to technology in a way that is intuitive and unselfconscious, while digital immigrants are better qualified for a longer view, a critical perspective on the overall picture.

Fears and Strategies

A recent survey carried out by Spain’s Interior Ministry found that parents’ main concern regarding their children’s internet use has to do with the risks arising from what other users (strangers or acquaintances, adults or other young people) may do to their children. Second came fear of their children accessing content that is not age-appropriate. Few parents expressed concern at the way their children may behave in relation to other users. In spite of these fears, the study found that these issues are only discussed in half (54.4%) of all households with children aged 10 to 17 who use the internet (according to the CIS barometers 3057 and 3131, March 2015 surveys). A quarter of families reported that they had talked about the subject “at least once”, and the subject is still taboo in 20% of households. The survey did not ask the reasons why families did or did not speak about the risks and opportunities of using ICTs, but the results show that one in five minors are more vulnerable to the dangers because they do not have somebody to give them advice, guidance or answers to their questions. This leads to a situation in which, to a large extent, parents’ idea of how their children use the internet does not correspond to reality.

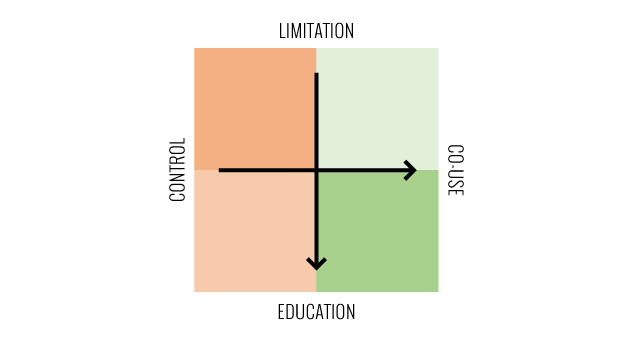

The theorist Sonia Livingstone explains that parents are the mediators between online risks and the opportunities that the internet offers their children. Dialogue is part of what has been described as “active mediation”, but it is just one of several parental mediation strategies that have been defined. This classification takes into account the relationship between control / co-use, and restriction / education. These strategies are not mutually exclusive, so different combinations are possible. Pure control includes strategies based on monitoring and supervision. It can mean monitoring what websites children use, checking their profiles on social networks (what they post, who their contacts are) and looking at the messages they receive. These aren’t considered forms of mediation because they are often carried out when the child or teenager is not present. Supervision provides information on the child’s behaviour, and it can be a prelude to other strategies.

When it comes to mediation, three approaches have been defined: technical, restrictive, and active. The use of tools that allow parents to control content in order to avoid spam and viruses is a form of technical mediation, in which limits are set using software. Restrictive mediation works by setting limits as to the type of information that users can publish, the amount of time they can spend online, the sites they can and cannot visit, etc. And lastly, active mediation relies on talking, sharing, making suggestions, and encouraging children to explore for themselves and to share their questions, doubts, and discoveries. We could say that technical mediation combines control and limitation, restrictive mediation is based on co-use and limitations, and active mediation falls within the paradigm of co-use with the objective of educating users. The ideal scenario is to tend towards the green quadrants, particularly the combination based on education and co-use.

Each approach has specific components that can contribute to the process of acquiring digital literacy. Co-use and training also require a certain level of control and delimitation. But, wherever possible, it should be explicit and reasoned.

10 tips you can start using right now

- Negotiate and educate instead of prohibiting: set limits in an explicit, reasoned, negotiated way as far as possible. Always explain the measures in a way that your child can understand. If you avoid imposing, you will be more likely to reason and explain the actions that you carry out. An imaginative strategy is to sign a contract in which parents and children set rules for use, terms, and limits, and specify the penalties that will apply if they break these rules. Safe Surfing Kids has published a model that you can adapt to your own situation.

- Yes to technical mediation, but explain it too: Parental control programmes are a genuinely effective technical means to avoid undesired content. But it is important that children and teenagers realise that the risk of violent or sexually explicit material appearing has been removed from the family’s computer. This will help them to understand that some environments are more protected than others, and that it is possible to regulate alert levels. The blog Pantallas Amigas (in Spanish), specifically on this issue, is a useful resource.

- Talking about ICTs: Mobile phones and other technological devices can be a source of conflict in many homes (usually because children pay more attention to them than to their parents or their homework, or because they spend too much time on them, etc.) This needs to change. In the video La Família en Digital (in Catalan), Jordi Jubany describes the benefits of making room for technology within the family, and of doing it at the intergenerational level.

- Individual use, but with others: Experts recommend that the computer with internet access should be located in a communal space (dining room, lounge room). It is important that children and teenagers should be able to surf and explore the net on their own, but we should set aside time to sit with them and see what they do, what their interests are, what they search for and how they react to the stimuli of the internet or of other users. The process is similar to sitting down and watching television with them with a mid-afternoon snack, to tell them how much time they should spend watching and to show them how to choose a channel and how to decipher the messages that the shows transmit, so that they can understand and deal with them. The longer you spend accompanying your children online, the more likely they will be to spontaneously share their questions.

- Identify personal data: It is important for children and teenagers to know what personal data is, why it is sensitive, and why they should not give it to anybody without a good reason. Information that is considered sensitive on the net includes names, e-mail addresses and passwords, residential address, bank account numbers, etc. The adventures of Reda and Neto (in Spanish) are short animations that can help you to start the conversation in a fun way. You can also discuss these issues when your children sign-up to a website, service, or application.

- Beware of taking “candy” from strangers: You need to explain that it is easier to fake an identity online than in real life. This means that when minors use social media, it is essential to limit the strangers they include in their contacts. 20% of minors have received proposals to meet strangers face-to-face. In Catalonia, public bodies have published practical handbooks to deal with these issues. It is important to develop a relationship of trust, so that your children feel that they can let you know if they are involved in unpleasant situations. Face-to-face meetings should be discouraged, but minors who do arrange to meet should always make sure they tell somebody in advance and that they meet in a public space.

- Talk about the digital footprint: It is important for children and teenagers to be aware of the traces their online activity leaves, even when they think they are carrying out ephemeral interactions. A good example is an experiment carried out by a British schoolteacher to show her students how “private” a photo on the image messaging application Snapchat really is. She asked students to take a photo of her, holding a sign that read: “This is a ‘private’ Snapchat pic. Please share, like, and comment where you are. Help me show my ‘primary’ class how private this pic. really is!” Suffice to say that the growth was exponential, leading to 27,000 likes from people in England, Australia, Denmark, Canada, and many other countries around the world.

- Shall we configure your profile together? If your children want to create a profile on a social network and you think they are at an appropriate age to do so, you can help them to configure their profiles. This will give them an opportunity to think about what personal details they should share and what photograph they should choose (preferably an avatar or a photograph that doesn’t identify them). Together, you can also go over the privacy policy of the company that owns the social network and configure the privacy settings as desired. By default, you should always try to restrict contacts, and make sure that they have to be accepted one by one. Since 2014 Facebook offers a feature that makes it simple and quick to check privacy settings.

- Three questions before posting anything: When we use social media we tend to publish opinions and images almost before we think about what we are saying, how we are saying it, and how it could be interpreted. Children and teenagers should be encouraged to ask themselves three questions before they post (the social media version of counting to ten before you answer):

- the euphoria rule: would you post this in two hours time?

- the embarrassment rule: would your grandmother/grandfather/family feel embarrassed at reading this?

- the “bad guy” rule: could somebody with bad intentions use this information to find you or hurt you?

- Actions over words: As comic strip character Mafalda says: “I like people who say what they think. But I especially like people who do what they say.”

Conclusions

It is important to work towards ensuring that children acquire a good level of digital literacy, based on co-use and education, with the appropriate doses of control and restrictions. We need to find solutions that work as long-term strategies: the most important solution is to create critical users who know how to identify present and future threats, and who have the tools and resources that they need to respond and protect themselves.

We can use this challenge to implement educational processes based on understanding, no a spirit of self-improvement, learning, curiosity about the world around us, and teamwork between parents and children. Children and teenagers actively participate on the internet and social media, that is now an indisputable fact. As such, they should be taken into account and allowed to play a significant role in the decisions that we make regarding their relationship with ICTs. We need more initiatives to pool together and educate and enlist parents, grandparents, relatives and educators from all fields in order to accompany these young citizens-in-training. As we accompany them, it is important to remember that children learn from what they hear, but above all from what they see.

We also need to take action at the community level: lobbying for recognition of the rights of children and young people in the digital world, for example. At the same time, we should lobby industry and online service providers to facilitate services that are more adapted, transparent, and tailored to users. Nobody claims that it will be easy, but we probably all agree that there is a pressing need for this new approach.

Some more links to explore

The first is in English, the others in Catalan or Spanish:

Leave a comment