Alice B. Sheldon retouching a photo | jamestiptreejr.com | No known copyright restrictions

This year, 2020, fantasy and science fiction are celebrating such important centenaries as those of Joan Perucho and Isaac Asimov, but nobody remembers that in 2015 that of Alice B. Sheldon was underlined. Nor that the prediction by Roberto Bolaño in Amulet – “Alice Sheldon shall appeal to the masses in the year 2017” – has finally come true. The majority of people, in fact, are ignorant of almost everything to do with this great renewer of the genre, known by the male pseudonym, taken from a jar of marmalade, of James Tiptree Jr. Epistolary friend of Philip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin, today the mysterious Tip would no longer, however, make any sense: it is women like Sheldon who are heading up the best of science fiction, and prizes such as the Hugo and Ignotus Awards have confirmed this in recent times.

Exactly half a century ago, i.e. in 1970, a young science-fiction fan called Jeffrey D. Smith made the most of a tip from Harlan Ellison to send to the mysterious James Tiptree Jr., an interview designed for the modest magazine Phantasmicom. The great works of the surprising Tiptree – “The Screwfly Solution”, “Houston, Houston”, “Do You Read?” and “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” – would appear in the immediately subsequent years, but the first tales of this storyteller, whom nobody had ever seen in person, had been circulating for two years, and Tiptree and his sole means of contact – a post-office box in Virginia – would raise all kinds of speculations. For some, he was a secret services official; for others, a government servant; and with speculation being the order of the day, writer Robert Silverberg would come to write that he must be “a man of 50 or 55, I guess, possibly unmarried, fond of outdoor life, restless in his everyday existence, a man who has seen much of the world and understands it well”. Smith himself, who would also end up being a close friend and trustee of Tip, would for years take it for granted that the author was a man and he reflected this in what would be their first and only interview as such.

The presumed man called Tiptree, however, possessed singular literary virtues: besides his electric and creative style, he imagined like few the capacities for reasoning of aliens, mixed the galactic battles of the space opera with the transcendence of death and, surprise surprise, exhibited a not-always-evident feminist awareness, but one completely explicit in tales such as “The Women Men Don’t See”. In this story, the indeed sexist narrator of the story, Don Fenton, is incapable of understanding the situation in which a mother and her daughter, the Parsons find themselves, to end up preferring an alien life rather than an alienated life among fellow humans. To top it all, furthermore, Tiptree Jr. proposed in many of his texts daring variants in sexual, reproduction and gender aspects. This would soon win him the sympathies of great pioneers such as Joanna Russ and Ursula K. Le Guin. As can be inferred from their letters to him, this man, whichever way they looked at him, was like them.

And he was like them, of course, because he wasn’t a man but, as we now know, a woman called Alice B. Sheldon; a woman born in Chicago in 1915, with a doctorate in Psychology, a former member of the armed forces, painter, graphic artist, art critic and many other things in which she had successfully forged a career despite infinite oppositions that today we would undoubtedly label patriarchal. The discovery of her true identity, in 1976, was due to one of the few errors committed while she was writing letters with half of the American sci-fi universe: she mentioned that her mother, also a writer, had just died. Upon reading the obituaries for Mary Hastings Bradley, the mother of Alice B. Sheldon, friends who had never seen Tiptree added two and two together and the answer to the genre’s greatest mystery in the seventies was revealed, although the author never dropped the name: together with others such as that of Raccoona Sheldon, supposedly her protégé, the pseudonym that had made her famous continued functioning until the day of her death and still does today except in such essential works as the biography Alice B. Sheldon, by Julie Phillips.

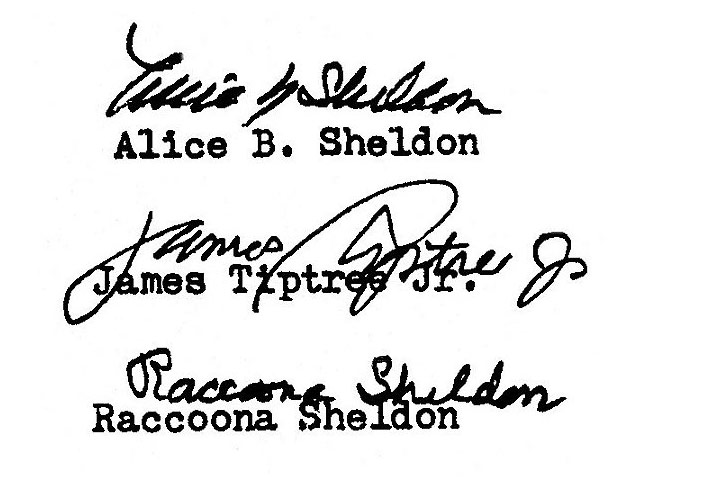

Autographs by Alice Sheldon and her pseudonyms, James Tiptree, Jr. and Racoona Sheldon | Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain

There has been much debate, not all of it fortunate, regarding the Tiptree/Sheldon case. The writer, as well detailed by Phillips in the aforementioned biography, justified the choice of male pseudonym as a literary game, half due to the fact that she had already had to fight hard on too many fronts for women’s liberation and she suddenly wanted the freedom to simply invent stories. Here is an important nuance, then: Alice Sheldon was not obliged, as in older cases, to use a male pseudonym, and nor was it needed by her colleagues and friends Russ and Le Guin; but rather like J. K. Rowling, who put neutral initials in front of her name some years later, Sheldon saw how the possible ambiguity could benefit her. Always pioneering in matters of feminism – it is only necessary to recall the “inventor” of the genre, Mary W. Shelley, daughter of the “mother” of the movement, Mary Wollstonecraft – science fiction was, in some aspects, more open than the society of the time, but at the same time it experienced a hardly edifying inertia that would still afford privilege until the new millennium to male names over those of women. And we are talking, with Tiptree in the seventies, of a period in which, at least in theory, the third feminist wave of history had begun to take place. Perhaps for that reason, Le Guin, who herself wrote letters with Tip for years and discovered when everyone else did that in reality it was Alice B. Sheldon, was incapable of condemning her. Hers are the famous words “She lied to us yet she never betrayed us, not once”.

Thus today, in full swing of the fourth wave of feminism, fortunately also with impetus in the world of letters and even more so in that of science fiction and fantasy, it makes a lot of sense to recover the Tiptree/Sheldon phenomenon. It is nearly a century ago, yes, and it does not permit obvious readings, nor popular vindications, nor clear slogans, but the broken mirror offered by the female author, supposedly male in her day, of “The Women Men Don’t See” enables conclusions to be reached that are as complex, unusual and fascinating as those of her works.

Thus, and beyond the nuances that would not fit into these lines (among them, the need to bring Tiptree out of oblivion, and also to denounce the lack of Tiptree’s works alive in Spanish and even fewer, not to say none, in Catalan), a good starting point to compare the current situation of women in science fiction with respect to the years of Sheldon would simply be to observe the lists of winners of the best-known prizes. James Tiptree Jr., officially (he withdrew from one edition precisely with “The Women Men Don’t See”), won three Nebula Awards and two Hugo Awards, the latter in 1974 and 1977. Without counting her, in the entire decade of the 1970s, only seven texts by women won any Hugo Awards (out of a possible forty). In short, and in a very eloquent contrast, in the 2019 Hugo Awards, the latest held when writing these lines, women swept the board in all the relevant categories: Mary Robinette for best novel, Martha Wells for best novella, Zen Cho for best novelette, Alix E. Harrow for best short story, Becky Chambers for best series and Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda for best graphic story.

Before the 1970s, just a handful of occasional names.

During the 1970s, fewer than a quarter.

In 2019, all of them.

For those who think that this might be biased data, besides inviting them to compare the number of male and female winners in recent years with respect to any edition in the 20th century, one could add to them the list of winners of the latest Ignotus Awards, presented last November by the AEFCFT (Asociación Española de Fantasía, Ciencia Ficción y Terror): Cristina Jurado winner of best novel, Nieves Delgado of best novella, Rocío Vega in short story and also in anthology, Becky Chambers in foreign novel, Nnedi Okorafor in foreign tale, Emil Ferris in comic, a recent translation of Ursula K. Le Guin in essay, the best article for Teresa P. Mira de Echevarría and even the best website for activists of the genre written by women, La Nave Invisible. In other words, women won in all categories except for that of illustration. What would Tiptree Jr. make of such lists as these? What has changed, between the third and fourth waves of feminism, in the world of science fiction and fantasy? If it has happened in English and in Spanish, is it happening in general? And can any conclusion be taken from all this?

Alice Sheldon at the river | Wikipedia | Public Domain

There is another way of viewing it: in the English-speaking world, the first time that an anthology of – women only – science fiction authors was published was, of course, in the 1970s. Specifically, in 1974, by the legendary Pamela Sargent and under the title Women of Wonder: Science Fiction Stories by Women About Women. As explained by academic Teresa López-Pellisa, co-anthologist of the recent volume Insólitas, this did not happen in the Spanish language until 2014, when Cristina Macía and Cristina Jurado promoted the first of the four editions to date of Alucinadas. In less than five years, however, a good handful of anthologies have emerged to start rewriting the canon, including Premio Ripley, Poshumanas y distópicas, Terroríficas, Insólitas itself – in the Spanish-American sphere – and others on the way, whether by current authors or classic but forgotten ones. If we add, by way of example, the Cuban Deuda temporal or the Mexican La imaginación: la loca de la casa, and if we follow the studies of specialists such as Lola Robles or López-Pellisa herself, it is obvious that things have not only started to change in the United States.

For many experts, in fact, the mass incorporation of women authors, readers, publishers and prescribers into everything that we call non-realist or non-mimetic genres is already clearly one of the main elements that are renewing, if not revolutionising, science fiction, fantastic literature and company. Together with others such as hybridisation, glocalization, gamification, posthumanism and the growth of the LGBTi and queer focuses, the reviewing of themes, forms and approaches that this historic step forward by female authors is producing will only be able to be fully reached after a time, but we are already in a situation to affirm that it will be major. It is only necessary, in this sense, to note the build-up created in the first two decades of this millennium with names such as those of J. K. Rowling, Suzanne Collins, Stephenie Meyer, Kameron Hurley, N. K. Jemisin, Becky Chambers, Anna Starobinets, Susanna Clarke, Elizabeth Moon, Lauren Beukes, Ann Leckie, Aliette de Bodard, Nnedi Okorafor, Ana María Shua, Samanta Schweblin, Mariana Enríquez, Daína Chaviano, Laura Gallego and the official veterans in Spanish Elia Barceló, Cristina Fernández Cubas and Pilar Pedraza – to name just over a score. The list could easily be doubled and even tripled if we add living veterans such as Margaret Atwood, Connie Willis and Angélica Gorodischer – and we would obtain a payroll perfectly equivalent in attention and capacity to find audiences of the entire previous history, from Christine de Pisan and Margaret Cavendish half a millennium ago to the 20th century in its entirety. (That said, it would be up to another analysis to determine what part of this comparison is due to the current boom and what part to the systematic invisibilization of women authors in the genre over the course of history: a phenomenon that has led López-Pellisa to name them, with an appropriate reference to the wife of Zeus forgotten by everyone “The daughters of Metis”.)

One last note in this short text, that aims to pay tribute to Tiptree/Sheldon as a precedent of the current revolution: what is the situation in the Catalan language? If, as we said, the phenomenon is clear in English or Spanish, does the same happen in Catalan? The most precise answer, following the previous parameters is that not, not yet. No, in the recent Ictineu Awards, the Catalan prizes for the genre, women did not predominate, although the SCCFF (Societat Catalana de Ciència-Ficció i Fantasia) has been paying tribute for some time to women pioneers such as Rosa Fabregat, Montserrat Galícia, Margarida Aritzeta and Carme Torras. Despite the fact that in recent years, there have been successful recoveries of genre works by classics such as Mercè Rodoreda, Maria Aurèlia Capmany and Víctor Català – our very own Tiptree avant la lettre – the work in this field is sufficiently important as to be able to dream about an academic in the style of Robles or López-Pellisa re-writing the hyper-realist Catalan canon. As for anthologies, ultimately, none of women writing fantastic literature in Catalan exists. Not, at least, until this February, when publisher Males Herbes will release the first, with some fifteen new female voices talking about the unusual under the title Extraordinàries. Is this a symptom? A possible turning point? The evidence of a change in paradigm, in which, to paraphrase a tale by Tiptree Jr., the women who are renewing science fiction and fantasy are starting to be seen also by men, by all men, as both men and women deserve and should be seen without further consideration? Because deep down, don’t let us deceive ourselves: the great, pioneering, visionary Alice B. Sheldon put it perfectly; it is men, certain men, also within the genre, who still act like the character Don Fenton and do not understand the Parsons and their contexts. It is they, and their heteropatriarchal heritage, who are boycotting the change, even unawares. It is they, and the increasingly few women who act like them, who do not see them, who do not want to look at them if not, like Fenton, in their most biased dimension.

The difference, this time, is that the women of the story will not leave with strange creatures. It will be the less sensitive, or less attentive men who will slowly become, if they do not accept the just demands of the daughters of Metis, of another world. It will be these men who women and the rest of men will cease to see or will see only as fictions of an era. Of a past era. Monsters or extra-terrestrials.

Leave a comment