Robot from the movie The Monster and The Ape (1945). Source: Flickr

One of the challenges inherent to robotics is the creation of an automaton that looks and behaves exactly like a human being. But what happens in the meantime? The “uncanny valley” hypothesis holds that when a robot looks and moves almost, but not exactly, like a human being, it causes a response of disconcert and revulsion in the observer. Several approaches have been used to try to explain this aesthetic phenomenon, which is not proven but has nonetheless become widely know in the last few decades, even finding its way into popular culture. It is a conjecture that implies a question: What makes us human in the eyes of others?

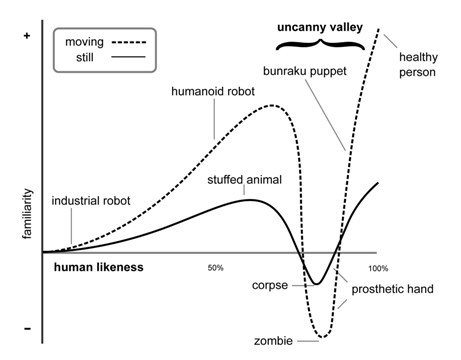

Forty five years ago, robotics professor Masahiro Mori published an article in a niche publication in which he discussed a curious observation. In his experience, he had found that humans feel increasing empathy towards robots that have a more humanoid appearance, but only until the similarity becomes too great. According to the Japanese scientist, at this point humans feel a strange sense of revulsion or aversion, which would only be overcome by a hypothetical replica so perfect as to seem to be a real person. Mori graphically represented his theory by plotting a line of sympathetic emotional response that goes up, dives steeply, and rises again, creating the “valley” that gives the phenomenon its name.

Graph of Masahiro Mori’s “uncanny valley”, showing a relationship between empathy (shinwakan) and human likeness.

The robot as heresy or the evil twin

Various theories have attempted to explain the “uncanny valley” phenomenon from different disciplines, ranging from philosophical to biological perspectives, and from the profound to the banal. The more profound theories include those that claim that the revulsion triggered by robots is based on a religious-cultural fear of any autonomous creature that is not God’s creation. The Hebrew legend of the Golem, the clay figure that a rabbi created and breathed life into, and its modern version in the guise of Frankenstein, are variations on the myth of the artificial being as a monster with the power to kill its creator.

The theme of the rebellious creature is also a recurring motif in contemporary science fiction, giving rise to the stereotype of the android – and to some extent, science itself – as a potential threat. In this sense, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard sees robots as the sublimation of human control over objects and nature, but the threat of rebellion is inherent to all submission and all slavery. The rebel android, Baudrillard argues, symbolises the confrontation between the scientist and his double: a being created in his image and likeness, which through rebellion becomes his equal. The recent development of “autonomous weapons” updates this anxiety for the present, bringing fear of artificial intelligence into the field of war.

The figure of the double is another possible cultural approach to understanding the uncanny valley phenomenon, with aversion to the robot seen as a response to the doppelganger motif. In Nordic and Germanic folklore, seeing one’s double is considered to be an omen of death or of future misfortune, and an embodiment of one’s dark side.

The robotics field itself has also openly explored the concept of the double, with Hiroshi Ishiguro’s Geminoid being the best-known example. For the last ten years, this Japanese scientist has been developing robots based on real human models, with the aim of understanding how to endow them with a sense of “presence”, how to capture and transmit the qualities that make them appear to be alive. To this end, Ishiguro has designed replicas of himself and of some of his collaborators, with realistic attributes such as flexible, pressure-sensitive silicon skin and motors and mechanisms that simulate breathing.

Image from Area V5 piece by Louis-Philippe Demers about the “uncanny valley” hypothesis, now shown at HUMANS+ CCCB’s exhibition.

A more prosaic valley: Misunderstandings, expectations, and illness

There have also been less poetic approaches to the “uncanny valley” hypothesis. In the field of psychology, for example, the phenomenon has been attributed to a hypothetical cognitive dissonance between what we see and what we expect. In other words, between finding humanity in something which we know to be lifeless or, conversely, perceiving the artificial in something that appears to be alive. As French physicist Alexei Grinbaum puts it, “when identical copies fail to be fully identified with one another, both their identity and their difference become significant.”

Along similar lines, an experiment carried out at the University of California with the support of Hiroshi Ishiguro used a brain scanner to measure the response of a group of observers to three different test subjects: an Ishiguro Geminoid, the real person that he had modelled it on, and an obviously artificial automaton. The study found that brain activity only increased in response to the movements of the human-looking robot, suggesting that the brain was attempting to process the incongruence between the appearance of the android and its movements, or in other words, between what it was and what the mind expected it to be.

It is only fair to mention the explanation that Mori himself hinted at in his 1970 article. In spite of admitting that he had not deeply analysed the reasons for the uncanny valley phenomenon, he claimed to be certain that it was bound to be “an integral part of our instinct for self-preservation”. Along these lines, some theories link the phenomenon to a self-defense reflex in response to death and illness. According to this view, the brain instinctively interprets the imperfect expressivity of androids as some kind of illness or immunological flaw that humans feel aversion to because of the possibility of transmission. The person who is ill is also a potential mate with low fertility, and as such would also trigger a response of aversion or revulsion.

A hypothesis still to be proven

Various experiments support the existence of the “uncanny valley” based on tests carried out with children, videogame players, and even monkeys, and using not just robots but also digital images and wax dolls. Nonetheless, the results are not consistent enough to unequivocally prove such a vague formulation, and scientists such as Cynthia Breazeal, Director of the Personal Robots group at MIT, do not even accept it as a hypothesis, relegating its status to mere intuition.

In fact, in 2005, Mori himself made a few comments publicly recognising the vagueness of his hypothesis. A dead person’s face can indeed be perceived as uncanny but, he argued, it sometimes transmits a sense of calm and peace. Similarly, the way of getting beyond the uncanny feeling may not necessarily involve designing more lifelike androids, but perhaps a human ideal, he said, giving the example of a Buddhist statue that can generate empathy because it is full of elegance and serenity.

Lastly, we should not end without mentioning a couple of the more light-hearted aspects of the “uncanny valley”. On one hand, if robots are a narcissist abstraction of human beings, as Baudrillard claims, our instinctive aversion is almost a taunt, the creature’s aesthetic rebellion against its creator’s ambition. On the other, there is an undeniably kitsch aspect to some androids: bad copies, poor reproductions so strange as to provoke fear but also sarcasm, or even arouse compassion. In any event, they draw attention to the philosophical and psychological implications of technology, which cannot ignore its function and its need to find its place in society. In an interview at the age of 85, Masahiro Mori, retired, once again hinted at this: “I don’t think the robots need to be humanoid. I actually think that it would be extremely difficult for a humanoid to help with the housework. It’s not possible to build one at the price points of vacuum cleaners and dishwashers.”

Therfer | 11 November 2015

Hola

Article interessant, d’un tema conegut però encara on cal fer recerca. Possiblement aquest ‘rebuig’ primat cap a un pseudohumà (?) però, en la meva opinió, lliga més amb altres peces de l’exposició que l’àrea V5, com dieu.

Molt bona expo!

Therfer

Equip CCCB LAB | 12 November 2015

Moltes gràcies! Si, és una exposició que convida a la reflexió.

Leave a comment