“A Bruxinha que era boa”, play by Maria Clara Machado. Rio de Janeiro, 1958 | Arquivo Nacional do Brasil | Public Domain

For centuries, the biggest phobias and anxieties of each society have found expression in this kind of wild theory which, despite emerging on the fringes and based on data that is doubtful to say the least, ends up plunging many people into fully-fledged conspiracy fever.

Frank Henry Little, better known to his neighbours in Butte (Montana) as Frank Little, was murdered in cold blood on 1 August 1917. This charismatic union leader had, years previously, joined Industrial Workers of the World and had just organized a dockworkers’ strike in Wisconsin when he was lynched and hanged by six men in broad daylight, without the authorities doing much to discover the identity of the criminals. In fact, everyone in public office in Butte (though not the 10,000 workers who attended the funeral procession) shrugged and muttered something to the effect that “you reap what you sow”, leading writer Dashiell Hammett to ask a simple question: what if everyone in this damn city was corrupt?

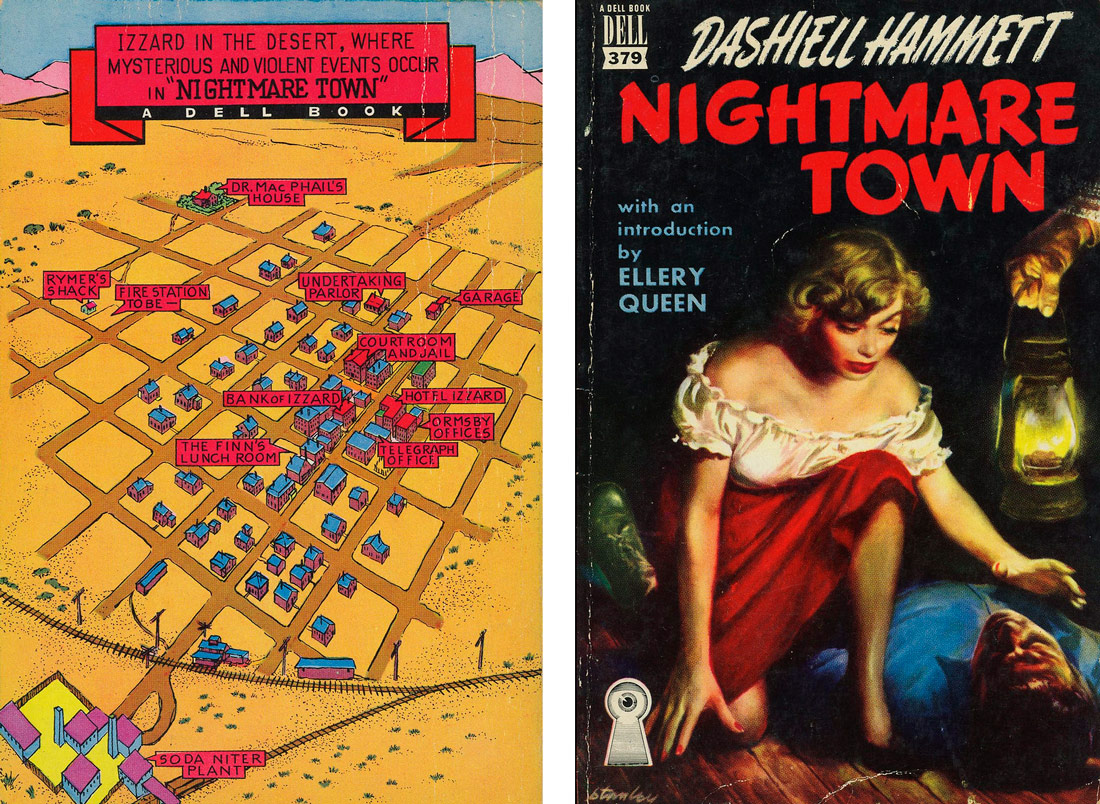

The result of that chilling flash of inspiration was Nightmare Town (1924), a short story which, to quote William F. Nolan, reflects like few others the vision of “a chaotic world, without shape or design” that characterized the author, for whom people like Frank Little never had a real chance, because the bank always won. The town in the title was Butte in the first draft, but was to become the fictional Izzard in the final version. Hammett was to return to the idea of a small community, like modern Sodom and Gomorrah, united around crime in his successful Red Harvest (1926), but Nightmare Town has the honour of being one of the first pure conspiracy fictions ever published. The main character enters the story with the gallantry of a classic adventure hero, but his stay in Izzard (where everyone around him seems to know something he doesn’t) is about to make him completely paranoid. The last passages of the story, in which the town seems to be consumed by a purifying fire, are as cathartic as they are falsely optimistic: Hammett was well aware that for every nightmare town that caught fire, another ten would take its place.

Dashiell Hammett – Nightmare Town

Nightmare Town was, then, a perfect compendium of the sins and vices of Prohibition USA, so characterized by its episodes of violence, corruption and everyday transgression that the conception of a town as an immense fraud was not actually that wild. Like many other conspiracy fictions that followed, its purpose was to bring together in a single narrative all the social fears and anxieties of its time, since we only have to study the wildest and apparently most marginal theories of each period to know what its collective nightmares are. The panic over a secret infiltration of Nazi agents into the London of the Blitz prompted Graham Greene to write The Ministry of Fear (1943), in the same way that the American cinema of the fifties seemed obsessed with the red peril (or the idea of Communists living hidden in “our” midst). In the aftermath of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the American people quaked with fear at the idea of not just an external enemy but also an enemy within: the possibility that their own government was conspiring in the shadows, a suspicion that the Watergate scandal did nothing but fan. Meanwhile, dictatorial regimes like Franco’s managed to ground themselves by a conspiratorial sleight of hand and turn the personal enemies of their leader into enemies of the homeland. The Judaeo-Masonic-Communist plot that had supposedly plagued Spain since time immemorial was, then, another sum of all fears, only this time travelling from top (the highest authorities) to bottom (the common people).

Conspiracy thinking always needs a Them vs. Us framework to function properly. Every conspiracy, from the rumours of Rosicrucian interference behind the events of the French Revolution to today’s anti-vax movement, is led by a minority elite that perversely and self-interestedly manipulates a majority that is much less powerful and, unless it wakes up and gets organized, much more docile. This unequal fight against the secret developers of the New World Order is equivalent, in practice, to declaring rebellion against everything that reeks of official version, but the most fascinating and at once terrifying thing about the times it is our lot to live is that this rebellion sometimes comes from the highest levels. Like Francoism, Trumpism was adept at bringing together all the fears of its charismatic leader into a single uniform mass, the globalist elites, who were directly blamed for maintaining a deep state, or supragovernmental power, above even the White House. If in the days of Watergate people looked at Washington with suspicion, Donald Trump managed to get a surprisingly high percentage of the population to believe what the conspiracy expert Jesse Walker called a “benevolent conspiracy”: the conviction that the President of the United States was working sub rosa to help those in need and end the dark reign of the deep state which, of course, was never anything but a formula to demonize the political rival.

I refer, of course, to QAnon, probably the most representative conspiracy theory of the late 2010s and early 2020s. According to a poll carried out by the NPR at the end of last year, a staggering 17% of the US population believe that “a group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media”. A further 37% of respondents said that they didn’t know, the icing on the cake being provided by a further 12% who supported another completely wild and, somehow, closely related theory: that many of the mass killings of recent years were actually fakes carried out by professional actors. The same satanic elites that control the deep state would therefore seem to be interested in putting an end to the second amendment using various theatricals to draw attention to the dangers of firearms.

What this survey actually reveals is the immense seductive power of conspiranoia for an increasingly high percentage of individuals who, during a particularly tense and confusing historical period, decide to embrace an anti-system populism that suspects any official version on principle. In Spain, too, we are seeing more and more how the extreme right is learning to bring its hate speech into step with conspiracy thinking: deep down, it is about instrumentalizing what conspiracy theories have always done better than anyone else and scaring the population with the sums of all fears, stewed up to feed mistrust in enemies without and within. Imaginary towns like Hammett’s Izzard continue to act as distorting mirrors of our reality, but rather than authors concerned about the way the system smothers its promises of progress, the main artistes are now demagogues hoping to pick up votes thanks to a generous dose of conspiracy panic.

We need, then, to believe in a possible rebirth of conspiracy fiction as a tool to detect and amplify evils present in our society, or as an ideal weapon to fight against the ultra-monopolization of the conspiracy mindset. Writers like Thomas Pynchon, William S. Burroughs, Robert Anton Wilson, Margaret Atwood and Umberto Eco blazed the trail: instead of letting fear and hate speech build narratives to bias electoral outcomes, let’s lay claim to conspiracy fiction as a territory to denounce this assault on the paranoid imagination, where down is up and there’s a place for every wild thought, because no one wants it to collide traumatically against the wall of reality.

Leave a comment