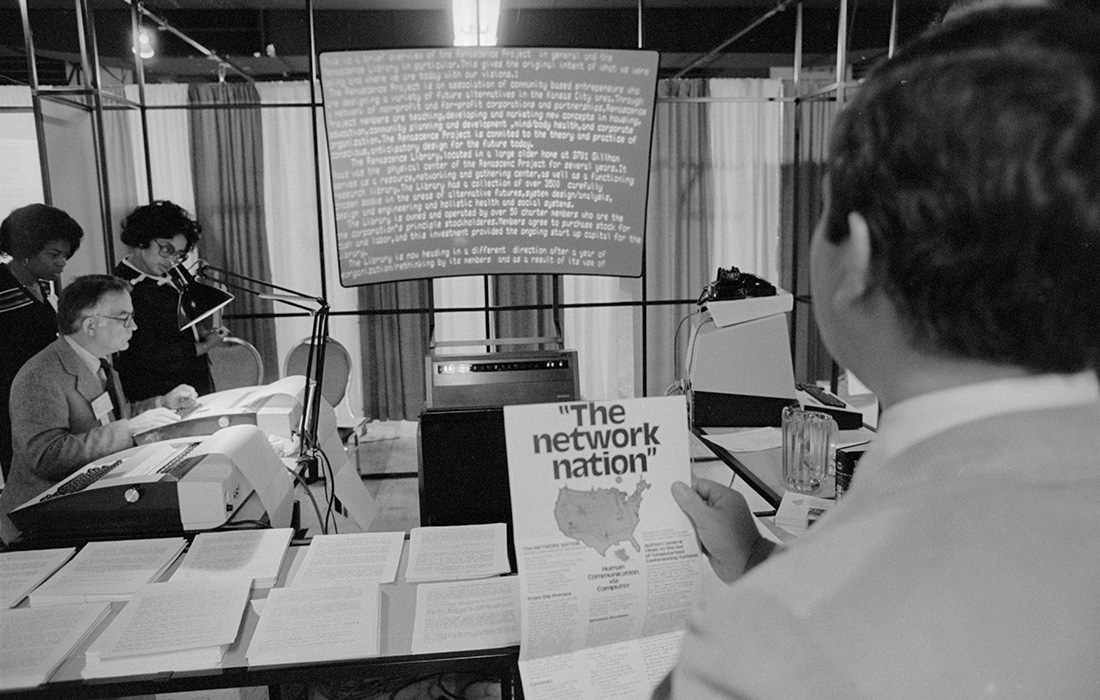

Visitors at a exhibit at the White House Conference on Library and Information Services. Washington D.C., 1979 | U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection. Library of Congress | No known restrictions on publication

Words consolidate the way we see the reality we live in, a reality we sometimes disguise with names that don’t make the thing: the cloud, entrepreneurship, mother nature, empowerment, etc. are some of the most battered. We take a look at some of these metaphors as a creative exercise and an excuse to rethink the glasses through which we view the world.

- On the beauty of metaphors, a poem by Josep Pedrals

- Reinvent Yourself, a text by Inés Macpherson

- Page 85, exercise 2, a text by Cris Zhang Yu – 张婷婷

- Euphemisms, Nyceness and Literality, a text by Irene Pujadas

On the beauty of metaphors

A poem by Josep Pedrals

Often, metaphor is an accident:

the lack of a word that serves to describe

our own way of seeing the moment

(or the perception of a particular phenomenon,

or perhaps the impression caused by delirium….)

means that, being unable to speak literally,

we express the thing using a stand-in term,

whatever that may be.

Using analogies, we draw a parallel

between what we say and what we would like to say,

and this resemblance between the lens

with which the world is shown and the thing itself

generates a coherent, chance link.

The new words for the referent

depend on the field that the lens instils,

and, in this way, the structure creates a bond

that is very useful and also brand new.

But, really, what is surprising

are the relationships between the two elements,

the great novelty is this condominium.

I mean that what’s great about the experiment

is that the words were there from the very start.

So, what matters in this procedure

is that it is economic because, in its artifice,

it freely uses existing words,

it is practical because it doesn’t need to specify

and, in vagueness, there is an understanding,

and it is very creative because it is the birth

of a synapse that creates an idyll

between totally divergent realities.

But if the creative part is lacking,

then the metaphor is mere vice,

it is conventional, it is not freshly made.

What’s great about the game is that it is

half makeshift, that it can be blown away by the wind,

that it works within the order wherever it springs up

or that, really,

it brings a concept that is so new, so surprising,

that it remains for ever just as it comes to us.

In this way, metaphor is pure movement,

it seeks to free itself of things that pin it down,

and that’s how we like it, nice and fresh and new,

like a mere whim.

Reinvent Yourself

A text by Inés Macpherson

“Reinvent yourself” I read in the notebook I was given to make the most of this crisis to discover what I have to offer the world, what my place is. It’s a notebook full of colours, boxes and motivational phrases that welcome me from the corners of the pages, encouraging me to think that my ideas will be marvellous and I’ll be an extraordinary entrepreneur. I’ve also got several books, step-by-step guides, lists and a mug that reminds me that I’m great.

I look at the sentence. It’s a very short sentence. A verb, a pronoun, that’s all. A strapline that’s been repeated until it’s become an absolute truth, an obligation that impinges on us all at some point, because we are not enough as we are. We have to invent ourselves. Because, ultimately, what does reinventing yourself mean if not inventing yourself again? But now that I think about it, at what point did I invent myself? Did I create myself? Construct myself? I wasn’t aware of it.

I turn the page. “You can make it happen” says a box that invites me to think what my ideal job would be. Is that what it’s about? Or should I adapt to the system, to the jobs that exist or the ones I imagine will exist? As well as inventing myself, do I have to be a clairvoyant? I’m not sure about that. My ideal job is now obsolete. I’d have to adapt it to this new, constantly changing reality that passes us by as if we weren’t part of it. A society made up of people who don’t really exist, because they’re numbers. “Think positive”, I say to myself. I no longer need to read it anywhere. I’ve been told it so many times that it’s now part of my vocabulary. But I’m not able to think like that.

I’m going to make coffee. That’s something I can make happen.

Page 85, exercise 2

A text by Cris Zhang Yu – 张婷婷

In my fifth year at primary school I wrote in my exercise book “p. 85, ex. 2. Explain the meaning of the following expressions”, beneath which I copied the first set phrase: “See eye to eye.” By then, they let us write the sentences in ballpoint pen, so I wrote it in blue biro. Then I took my pencil and started flipping through the previous pages of the book to see where in the text that phrase and its meaning appeared. I spent a long time searching among the pictures and illustrations, but I couldn’t find it written anywhere. Not this first sentence nor the others that came after it in the exercise. In the end I gave up: I didn’t understand why they were asking something that wasn’t covered in the lesson.

Could it be a misprint?

The next day, I told my best friend that exercise two on page 85 was very hard because it wasn’t in the book. Either that, or they’d made a mistake and put it in the wrong lesson. “But that was the easiest!”. she said in surprise. And she went on to explain what those set phrases meant. “But where did you find it??” I asked with admiration and a little frustration. “I don’t know! But when they say them at home, my mum and my gran explain them to me…“

So it wasn’t a misprint, then.

At mine, at my house, they explained the 成语 (chéngyǔ), set phrases of four characters in Mandarin. They also told me about the complexity of their structure, especially when they were used in poetry. I could really feel that complexity when my mother or father sat down and explained the meaning of the four monosyllables they had just uttered. But those, the set phrases on page 85, exercise 2, I had never heard before.

Euphemisms, niceness and literality

A text by Irene Pujadas

Flaubert is known to have had an obsession with the right word. But Flaubert also read his works aloud and, as a master of irony, he must have known that the meaning of words depends not only on the words themselves but also on the context, intonation, pace and gestures that accompany them—in short, on the human being behind them. Take for example the adjective “nice”. Everything that generates niceness is, somehow, naturally attractive: we imagine people who are easy, not twisted, who drink straight from the bottle and ask questions, and who, on leaving the party, offer to take the plastics down to be recycled. We think of this nice friend, and then of the friend we’re referring to, if someone expresses an interest, as “nice”: a person who doesn’t fit the canon of hegemonic beauty and who must also be very, very nice. If we don’t accompany this with another adjective, we accompany this “nice” with a gesture: a moment’s silence before uttering the adjective, shrugs and raised eyebrows, and other signs of apology—after all, he’s our friend, we love him, objectification makes us feel guilty and we believe, we really believe in the beauty of charisma. In the first case, we’re describing the nature of the friend, in the second we’re giving implicit information about that friend. In the first case, our communication is based on what we say, in the second on what we do not say. In the first case it is the exact word, in the second it both is and is not the right word. It is, because it says exactly what we mean, and it is not, because the meaning of the word has nothing to do with what we mean. So, how do we tell the difference? How can we tell if the emitter is talking about a friend who is nice in the literal or the euphemistic sense? Are we at the mercy of the intention and hermeneutic abilities of the emitter and the receiver, and, ultimately, of their complicity? Do we need more pointed questions? Do we need more literal answers? Aren’t they telling us, in any case, that we’re dealing with a person who drinks straight from the bottle and is friendly? This is how we talk about loved ones without wanting to hurt them, this is how people on the same wavelength understand each other, this is how the rough-and-ready and the intrepid end up in unexpected situations, and how people, all over, go home without really knowing what happened. This is, in short, how the right word is, at once, one and several.

Leave a comment