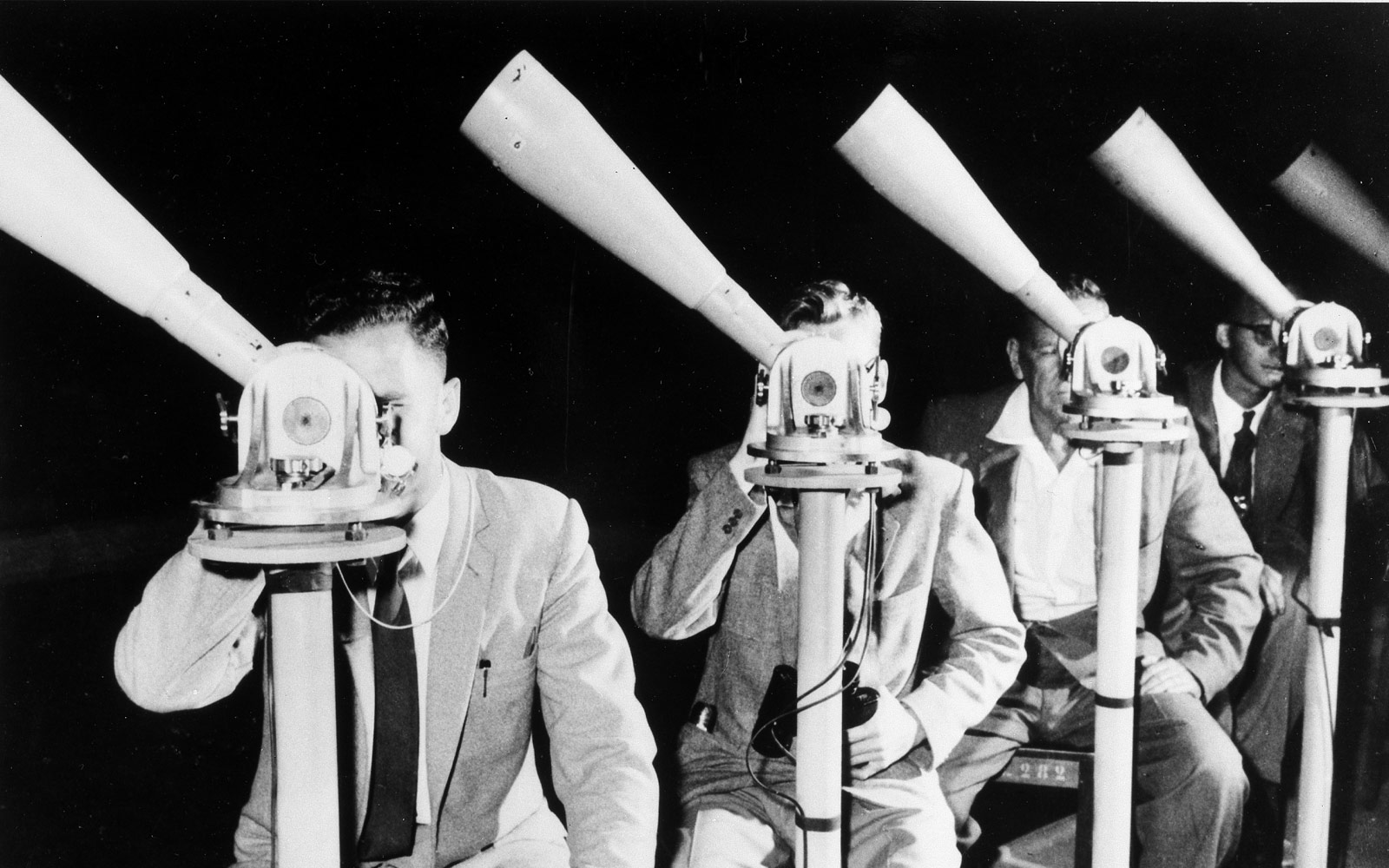

Volunteer satellite trackers in Pretoria. South Africa, 1965 | Smithsonian Institution Archives | No known copyright restrictions

Virtual reality introduces a scenario that is promising and totally new. For the first time in the history of technology, users have the opportunity to shape and validate a new medium as it develops. But even though the technological sector carries a lot of weight in the development of VR, we should not lose sight of the fact that it is the content, not the interface, that defines immersive video. As such, the success of virtual reality will depend chiefly on its capacity to generate its own language, and on the role that it assigns to spectators: the digital environment generates great expectations, and audiences want interaction to be a key part of the experience.

It comes as no surprise that the main prizes by which the Hollywood industry honours outstanding work in new digital media are called the “Lumière Awards”. There are extraordinary parallels between early pre-cinema devices and the birth of film on one hand, and Oculus Rift headsets, Google Cardboard viewers, and all the experimental immersive 360 video and virtual reality productions that have been made in recent years on the other. Dear Angelica, which won the 2017 best VR Animation Lumière (there are ten VR categories) has been hailed as a must-see for those who are interested in exploring this new language.

The new El Dorado for audiovisual media explorers?

Victorian scientist Sir Charles Wheatstone was credited with the invention of the first stereoscopes, which were soon followed by others such as the well-known Brewster stereoscope in the 1830s. These devices for viewing images with depth of field were part of a select list of pre-cinema instruments that gradually shaped early film and, with it, the construction of audiovisual language and culture. Something similar is happening today with each new device and each step we take in the production of VR narratives. We can argue that this is the case from the point of view of the individual reception of film if we look at certain parallels: trial and error of new devices such as Edison’s failed Kinetoscope and the invention of mechanisms to simulate stereoscopic vision, the creation of content for a new representation format that is still in embryonic form, the fact that shooting in VR or 360 video means images cannot be seen immediately but have to be edited and rendered (thus recovering some of the magic of analogue photography), and the beginning of academic reflections in the form of “manifestos”, such as“Not a Film and Not an Empathy Machine”, by leading digital narrative theorists Janet H. Murray. There are many similarities, but even so the context is different now and many factors are totally new, particularly they way in which researchers, companies and creators are laying the basis for the new media in ways that did not happen in early cinema.

One of the main factors is the fact that the media ecology that underpins this technology is unlike any that has come before, making it almost impossible to predict its evolution. The distribution and transmission of content and technologies linked to the new format are moving at a speed and on a global scope that are unprecedented in history. And at the same time, unlike previous media (photography, film, television, the internet, etc.), for the first time in history end users have the opportunity to participate in the creation of technological models for production and dissemination, and in shaping the new canons and languages of content creation, even before they are explored by certain social agents. This is largely due to the availability of players like the YouTube 360-degree video player, to the relatively low cost of 360 video cameras and similar devices, and to the global proliferation of smartphones, which mean that the general public has access to a new representational technology in its earliest stage, and thus the capacity to question, define, and validate it. According to a recent study over 6.3 million virtual reality viewers, chiefly Samsung Gear VR, made it into people’s homes in 2016 alone.

The second contextual issue is the exponential rate of creation of new platforms and technological devices associated with this new wave of virtual reality, created by companies that are constantly updating the devices they have invested millions of dollars in over the last few years. Capital investment is a factor that gives the sector certain credibility but it also raises speculation about the value of the medium itself (remember the dotcom bubble) and about the risk of capital outflow if the economic return on investments does not happen soon. These two factors, among others, mean that there is not much time available to producers and observers for critical reflection and analysis on future progress. This situation generates great expectations for opportunities, and means that the desire to be the first to arrive at the finish line prevails over more thoughtful approaches. And this also applies to viewers, who do not have time to educate a critical way of seeing. Even though distribution and access to productions is much greater than it was in the early days of previous media thanks to the internet, many audiences are still inexperienced. It is important to point out that even though many of these kinds of immersive narratives are being produced (the number of companies dedicated to VR grew by 40% in 2016 alone), we cannot yet speak of production on a mass scale. In fact, the figures are contradictory: on one hand, the amounts invested are enormous, but on the other, only around 100,000 users are registered on one of the largest VR platforms, HTC Vive. In addition, the gender difference is a cause for concern, given that almost 95% of active users in the network are male.

Despite or because of the conflicting data, only time will tell whether immersive video will take root. History’s dustbin is full of once-new media that were going to change the world and failed for various reasons. Media historian Brian Winston called it the “Law of the suppression of radical potential”, according to which the growth of a new technology is suppressed by the constraining influence of existing institutions, and that the greater its supposed potential for social change, the stronger this suppression will be (a theory that will not please technological determinists). In any event, we cannot deny that the impact of this wave of VR is infinitely greater than that of earlier waves, and that given the enormous amount of productions it is urgent to think about how we can influence this new format in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. This is particularly so now that VR is starting to find its way into many fields and areas that are exploring different approaches. One of the most important areas is documentary, where interesting works such as Witness 360 are being produced, but immersive video is also making inroads into animation, with examples like the acclaimed Allumete, journalism, and art. The new technology is also being used by NGOs and organisms like the UN in projects like Waves of Grace, as well as cognition, games, heritage, and literature, with adaptations like Lincoln in the Bardo.

Resituating language, viewers, and authors

In light of this new scenario, we still have to ask ourselves: what exactly is immersive video? What grammar does it use? What are the qualities that define it? Can we apply everything we have learnt in filmmaking? Or will we be limiting the freedom to explore if we simply apply the knowledge based on the language of earlier media like film and theatre? Recent projects are making it clear that this new format is not video “without a frame”, but rather a whole new format that is still in the process of being invented. Below are some ideas that can contribute to continue to shaping the debate.

First of all, we should not forget that the key thing about immersive video is not the interface – not the glasses or the headset – but the content. Just as film does not depend on the projection room, the darkness, and the surrounding audio, even though it all certainly contributes a great deal to the experience. But film is the production and editing strategies and techniques that we unconsciously absorb while we watch, and that make the experience absorbing and smooth. And reaching this point of absorption that allows us to talk about the suspension of disbelief took decades of work and exploration of the language of cinema. So, to start with: patience, some distance from everything we have learnt from filmmaking, and open-minded eagerness to explore other languages that may be helpful, such as dramaturgy and mise-en-scene, or videogames that strike a balance between the plot, action, subjective point of view, etc..

Because the fact is that in VR and immersive video mise-en-scenes the role of the viewer changes radically. In a 2015 TED talk, Nony de la Peña, one of the pioneers of this new wave of experimentation with virtual reality in the field of journalism, asked: “what if you could experience a story with your entire body, not just with your mind?” Janet H. Murray agrees when she says that “the focus of VR design is not the camera frame, but the embodied visitor.” A good example of this approach can be seen in the recent 360 series INVISIBLE, I: Ripped From Reality, which begins with a scene that focuses the viewer’s attention on a small part of the screen, while the rest of the surrounding spaces starts off being black, and then gradually fills with images. Another recent example of this “embodied” viewer is the recent PBS short My Brother’s Keeper, based on the TV series Mercy Street, which places us inside the experience of a war, and in which the position of the camera is key to the recreation. Because storytelling with immersive video is less about telling viewers a story, and more about placing them inside of it. And this raises more questions, because being inside a story does not mean being in one place. Perhaps it could mean sharing two places in one? And in the near future, perhaps sharing space with others at the same time?

The role of the viewer’s body is another key issue in new immersive video. There may be more similarities than you would expect with escape rooms, in which participants go into a themed room that has been decorated to represent a fictional space, and have to proceed according to a narrative that is not pre-defined, and that takes shape through their actions. But immersive video also falls within a genealogy of representation that could be traced back to Robert Barker’s 18th century panoramic paintings, which placed spectators within a particular scene and made them feel a part of it. And as professor William Uriccio recently reminded us in the first Virtual Reality and Documentary conference, the registered patents of Barker’s panoramas did not just place the spectator within the scene by means of the images that filled the whole room, but also used objects and materials displayed in the middle ground between the spectator and the perspective paintings on the wall. Essentially the same thing that VOID does today using current virtual reality technology.

But while it may be true that the sense of being present elsewhere provides some degree of immersion in itself, we have to remember that donning the headset is only the beginning, and that there is still a great deal to be done. As Murray says, using 360 video to show images of refugees, like The Displaced and similar projects do, does not add anything to what television is already doing. And this is the tension that we have to explore: the relationship between the feelings or sensations we want to provoke in viewers, and the content that we show them. Film and literature create that connection with audiences, making them feel empathy for what they read or see. Now we have to figure out how to resituate it in this new medium.

And finally, another of the important factors that need to be considered in relation to virtual reality concerns audiences in the broader sense of their experiences in the context of digital entertainment. The target audience of this new format is a sector that has grown up with the internet and videogames as important forms of popular digital culture. It is an audience that feels at home with interaction and expects it to be a fundamental part of the experience, and not just a simple choice between a few options, as is the case the most of the early VR demos (just as impressive and trivial as the Lumière brothers’ trains!). Audiences want to be part of the story, to have a sense of agency, of being involved in the story through their actions. And most projects so far fail spectacularly in this regard because they are passive or offer only basic interaction. This tension is important given that the great cultural expectations generated by VR lead to frustrating situations in which a medium is presented as the dystopian culmination of the hyper-technological future that has already arrived, but concrete examples are basic in terms of storylines and interaction. The eye-tracking interaction offered by devices like FOVE virtual reality headsets could open up a whole world of undreamed-of possibilities for audiovisual interaction.

We are currently at an exciting moment of creative opportunities and technological developments that some people believe will be a passing phase. Perhaps they are right, and in a few years this new wave of VR technology will be in history’s dustbin along with its predecessors. But we cannot deny that in the meantime we are seeing many new opportunities to attract audiences, new opportunities for audiovisual, artistic, research, and technological development, new ways of understanding and representing the world, and of explaining ourselves by different means. And in any case, we know that we are not very good at making predictions. If we regard VR with the same incredulity with which audiences regarded early cinema, the future will be bright and full of promise!

Jordi Prat Homs | 12 June 2017

Hola!

a posar en relaciò amb : https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/04/video-games-stories/524148/?

Posa la qüestió central, per a mi: seguir una narració o participar a un joc no tenen les mateixes rels antropològiques. No serveixen per a lo mateix per cadascú de nosaltres?

I potser es aixó que fa que la VR només funciona bé quan ens produeix una experiència augmentada (com viatjar, per exemple) i no quan intenta fer-nos viure una historia deixant a nosaltres la feina de explicar-la.

Leave a comment