Photogram of Metropolis, Fritz Lang (1927).

“Gestural interfaces that can be used to access, connect and process data captured in real time; shopping malls that recognise us when we walk in, and where polite virtual agents address us from interactive screens, remind us of our recent purchases and offer a selection of products tailored to our needs and tastes; the capacity to locate and track the movements of any person through the city… and even to predict the future.” This is how engineers at MIT Media Lab, Microsoft Research, and Austin-based Milkshake Media described the world circa 2045 when Steven Spielberg asked for their advice while preparing the screen version of the famous Philip K. Dick novel. Our reality is still nowhere near the massive, seamless network that structures and brings to life the world of Minority Report, but it would appear that this world made up of always-connected smart objects – or something very similar to it – is inevitable. As Adam Greenfield explains in his book Everyware: The Dawning of the Age of Ubiquitous Computing, computer ubiquity, in its numerous forms – augmented reality, wearable computing, tangible interfaces, locative media, near-field communication – is evolving every day, building bridges that bind the virtual world, or “dataspace”, closer and closer to the physical world, so that information is not only accessible from anywhere but also in everything.

See for example the recently opened Burberry flagship store at 121 Regent Street in London, an example of the spectacle of consumption that merges all the information from this clothing company’s website with the physical space. An augmented reality project in which information spreads throughout the architectural space by means of interactive screens that share information in real time through hyperspace. From watching a catwalk show or the launch of one of the products sold at the store, to the planet-wide sharing of cultural events programmed there.

Another example that connects information to context can be found in the numerous sensor networks that collect information in our environment, for purposes ranging from improving sporting performance to preventing damage from tsunamis, volcanoes and radiation leaks, or improving road traffic flow and safety –

Image taken from Murmurs of Earth by Brian Gardiner.

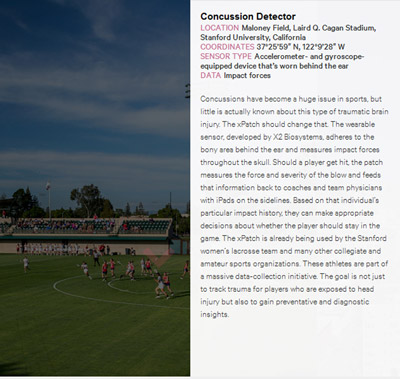

Concussion Detector is a wearable sensor that measures the impact of blows to the head suffered by athletes during games. The data recorded is sent to the coaches, who are equipped with an iPad where they can check them against the impact history of the players to help them make appropriate decisions about whether the player should stay in the game. As well as improving player safety, this project developed at Cagan Stadium in Stanford is also a massive data-capturing initiative that aims to improve diagnostic capacity in general.

Image taken from Murmurs of Earth by Brian Gardiner.

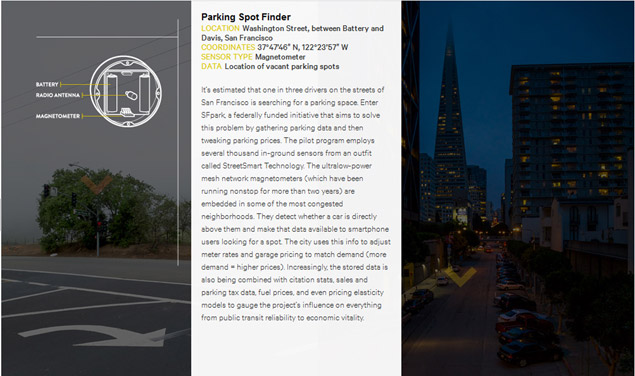

Another connected sensor project, in this case related to the development of smart cities, is the Parking Spot Finder, a sensor network that aims to improve traffic flow and clear up congestion in streets in the city centre. To do this, it detects whether parking spots are occupied and sends the information to smartphone users. The database is also used to adjust the prices of parking meters based on demand.

All of these sensor systems collect petabytes of data that are sent to the “cloud”, where they interact with other data sets and are processed in real time, in order to produce knowledge that is distributed through the net. A state of affairs in which collective intelligence linked to the Internet pervades the environment thanks to its latest evolution: the Data Web.

Web 3.0 or the Data Web is an evolution of Web 2.0, the Social Internet understood as a platform. It is a network in which software is offered as a service in order to connect users to each other. This Web, whose value lies in the contributions and uses of net users, is the start of collective intelligence. In order for the Web to be able to offer answers and create knowledge based on the information provided by users on a massive scale, this information must be in a form that can be handled, understood and worked with in real time. This is what the Data Web does. This new development is based on a series of standards and languages that make it possible to assign metadata to Internet content. These metadata, or data on data, are machine-readable and add information that enables all web traffic to be identified, located and monitored. The result is a system of related databases, in which different subsystems can be used to track all information related to a particular object, and to generate relevant responses. When these data do not just derive from our interactions on the Internet, but also from the network sensors that are spread throughout the physical environment – producing the data flood that characterises the Big Data phenomenon –, and when they also leave the limited frame of screens and become accessible in physical space through different types of augmented reality, then we have the Internet of Things, or, as Tim O’Reilly calls it, the Squared Web, or the Web encountering the world.

This encounter with the world, in which information materialises in our everyday surroundings through the dissemination of smart objects, leads us into the realm of Ubiquitous Computing.

Ubiquitous computing was described by Mark Weiser at the Computer Science Laboratory in Xerox PARC in 1988 as a “calm technology” that disappears into the background, allowing users to focus on the tasks they are carrying out rather than on the computer. Unlike virtual reality, which creates a disconnected world inside the screen, ubiquitous computing is an “embodied virtuality”. Dataspace materialises in the world through the distribution of small interconnected computers, creating a system that is embedded in the world, making computing an integral, invisible part of everyday life in physical space. The project that Weiser and his colleagues were working on in this sense consisted of a set of devices – tabs, pads and boards – that worked at different scales and could identify users and share and access different blocks of information from various physical locations. For example, a phone call could automatically be forwarded to wherever the intended recipient happened to be. Or the agenda agreed on by group of people at a meeting could be physically displayed to the group and then transferred to the personal diaries of each person involved. The result was a type of technology that was as intuitive and unconscious as reading, that moved out of the user interface and created a responsive space in which things could be done. A space in which the virtual nature of computer-readable data, and all the ways in which this data can be modified, processed and analysed, spread through physical space in a pervasive way (widespread dissemination).

There are still obstacles to achieving the pervasive space that characterises ubiquitous computing, such as: the diversity of existing operating systems and programming languages, which hinders communication among computers; the lack of design standards that would enable the homogenisation of the systems involved; the existence of gaps in the universal distribution of ultra broadband, which is necessary for the flow of these data; and the lack of real demand from the general public. But even so, the “intelligent dust”, as Derrick de Kerckhove, calls it, of this Augmented Mind is starting to spread throughout our environment. Aside from the sensor networks and augmented reality systems mentioned above, which we can access from our smartphones through applications such as Layar, we are also starting to see systems that identify users, allowing their actions to be automated. Commonplace examples include different types of cards with RFID chips, such as the transport cards used in some countries – Oyster in London and Navigo in Paris – and Teletac, which is used in Spain to pay motorway tolls. There is also the NFC, or near-field communication system, a mobile application that reads user-stored information such as credit card numbers or the codes of tickets booked and transmits it to nearby devices, so that the person carrying the telephone can make payments or enter shows. All of these applications provide contextualised information on demand, everywhere and in many situations, making it easier to interact with the information overload that characterises our society. They record data about our identity, location and interactions, turning them into new subsystems of data that can then be used by other systems. The fact that the system needs to identify all the objects and persons involved in order to be able to react to them means that any augmented or “pervasive” space is also a monitored space.

Collective intelligence increases the awareness of our surroundings and our potential options for interacting with it. But the pervasiveness and evanescence of ubiquitous technology makes it an unconscious mediation, a highly relational and complex system that is based on internal operations and interrelations with others, and that is imperceptible to the user. It is a system that can restructure the way in which we perceive and relate to the world, and also our consciousness of ourselves and of others. Without our being aware of our involvement in it, or of the magnitude of its connections, or even sometimes of its very presence.

In this way, ubiquitous technology becomes an “apparatus” as defined by Giorgio Agamben, based on his interpretation of Foucault’s use of the term. An apparatus is anything that has in some sense the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control or secure the gestures, behaviours, opinions or discourses of living beings. An apparatus must bring about subjectification processes that allow the individuals involved to interact with them. This means that they can be “profaned”, returned to the process of “humanisation”. Or, in other words, to the set of cultural practices and relations that have produced them, where they can be appropriated by human beings who are active and aware of their environment. The imperceptible nature of the fuzzy system of ubiquitous technology makes it impossible to profane, so that it becomes a strategic system of control at the service of a vague and imperceptible power.

Big data and the systems that materialise information in our environment would seem to have the power to make us happier, helping us to plan our cities and carry out our life plans. But we should stop and ask ourselves whether our cities and our environment in general really need to be “smart”. The qualities that make us engage with our environment are not its functionality and efficiency, but its aesthetic, historical and cultural aspects. The “embodied virtuality” of our post-digital world must be developed in conjunction with aesthetic strategies that allow us to visualise and understand the data flows that surround us, as well as the systems of smart objects that drive them. By doing so, we will not only be able to limit these systems to the areas of our lives in which they can be truly useful, we will also be able to appropriate them, leading to significant relationships. Collective intelligence and its ability to spread throughout our environment should increase our ability to act performatively in the world, making us conscious of the systems of human and non-human agents and relationships that make up our reality at any given moment. It should not become an imperceptible system that can diminish our capacity for agency and lessen our control over how we present ourselves in the world.

Mark | 17 July 2013

Great article, the internet of things will change everything in the coming years and bring the amount of data collected into the brontobytes. More information about that here: http://bit.ly/11w3yc1

Leave a comment