À l’école. Inside the postcard series: France en l’an 2000. XXIème siècle. (Atrib. a J.M.Côté, 1901). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 2008, American technologist Nicholas Carr published an article in which he argued that the Internet was eroding our capacity for concentration and critical thought, and even went as far as to claim that the Net would change the structure of our brains and our thought processes. Experts from different fields began to reflect on and study the relationship between the Net and our cognitive capacities. Some of them agreed with Carr, but others such as Clive Thompson dismissed these arguments, saying that the same debate comes up every time a new technology emerges. Thompson and other “techno-optimists” argue that the Net not only boosts our mental agility, it also allows us to learn more, more quickly and is, in short, making us smarter.

In Phaedrus, Plato tells us that Socrates was constantly complaining about a new invention. What will become of society? he would ask, disgruntled. The old sage feared that writing would mean the end of the culture he had so carefully cultivated, because it would lead people to completely ignore their memories and to become forgetful, empty of knowledge.

The philosopher even went as far as to suggest that as people would be able to access a great deal of information without the need for appropriate instruction, they might mistakenly come to consider themselves cultured, although, he said, they would actually remain ignoramuses without true wisdom.

Socrates was not far off the mark: the effects of that new technology were just as he had predicted, and people began to put knowledge down on paper so that it was no longer necessary to remember it. Nonetheless, it was not all bad news as Socrates had predicted, because far from wiping out culture, reading and writing actually helped to spread information, to stimulate new ideas and to expand human knowledge, if not wisdom.

Arguments similar to those that Socrates defended against writing have been cropping up again in our own society over the past few years, but this time the Internet is in the eye of the storm. In recent years, prominent biologists, theorists, psychologists, psychiatrists, philosophers, teachers, writers and technologists have been thinking about how the Net and new technologies are shaping our brains and the way we think.

Many people see the World Wide Web as an unprecedented cultural revolution, as proven by the fact that in one afternoon we can consult more information than that which was contained in the famous Library of Alexandria, and in a single click we can access more than a million terabytes of information, most of it free of charge. These techno-optimists, which include experts such as Clive Thompson, see the net as a positive development that is not only extremely beneficial and enriching for human beings, but also sharpens the mind and gives the brain cells a workout.

However, others maintain that intensive Internet use weakens our powers of concentration, our memories, and our ability to think deeply and creatively. They argue that Internet browsing requires a short, constantly changing focus, which may be detrimental to the type of sustained attention that is essential for studying, for example. They claim that the Internet is bringing about irreversible and not precisely positive changes in our brains: in short, they claim that it is making us stupider.

«Is Google Making Us Stupid?». The Atlantic magazine article.

The Google effect

American technologist and former director of the Harvard Business Review Nicholas Carr was probably responsible for opening the can of worms in 2008, when he published a controversial, provocative article in The Atlantic magazine entitled “Is Google Making Us Stupid?“, which he followed up with the book, The Shallows. What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (Norton & Company, 2011). In both, Carr wrote: “Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuits, reprogramming the memory (…) I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading (…) Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. (…) The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle.”

Carr fixed on the Internet as the main cause of this inability to concentrate. He argues that the Net is in fact teaching us to not-think and that our increasing dependence on technology is changing the structure of our brains. That the Internet gets in the way of formulating new ideas or developing old ones, and “encourages us to focus on the short and the quick, leading us away from focusing with more attentiveness on one thing. (…) When you open a book there is nothing else going on; it shields you from distraction. You turn on a computer and it is an interruption machine.”

A similar opinion has been expressed by North American essayist Howard Rheingold, an expert on the cultural, social and political implications of new communication media. He believes that the Internet encourages credulity, distraction and superficiality, and that as a result our minds are constantly struggling to be self-disciplined. The ubiquity of information makes us less likely to consider new lines of thought before we look online, he claims, resulting in less substantial thought processes that meet immediate needs at the expense of a deeper understanding.

Several studies carried out over the past five years back up the claims made by experts such as Carr and Rheingold and suggest that the Internet is in fact damaging the consolidation of long-term memory. When somebody knows they will be able to easily recover a piece of information they don’t bother to remember it, for example, as found by several studies carried out by Harvard, Columbia and Wisconsin-Madison universities and published in Science magazine, which measured the memory recall of a group of volunteers, and found that they retained less information if they knew they could access it later.

Indeed, why should we remember names, dates and historical events when we know we can find them on Google? The Internet has become what many experts are describing as a kind of extension of our memories, a phenomenon that has been dubbed the “Google effect”. It is not, however, new to the digital age. As far back as 1985, American psychologist Daniel Wegner showed that we tend to ignore knowledge that we know some other member of our group already has, a phenomenon that he called “transactive memory”.

The problem of the Internet, its critics argue, is that our brains need the information stored in our long-term memories in order to develop critical thought. We need unique memories in order to understand and interact with the world around us. If we entrust our knowledge to Google for storage, they say, we may be losing an important part of our identity.

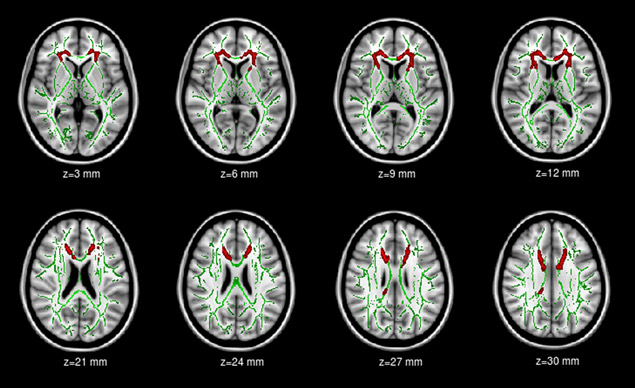

Recently deceased Stanford University sociologist Clifford Nass was one of the belligerent gurus against digital distraction, which he believed was an inherent aspect of the use of Internet and new information technologies. Nass was one of the first to make a link between attention deficit and multitasking. He believed that constant exposure to screens and the rise in the multitasking that Internet browsing encourages hinders concentration and the capacity for analytic thought. Moreover, he argued that it diminishes our empathy and can also trigger profound changes similar to those found in the brains of drug addicts. In a study led by the academic Hao Lei from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and published in PlosOne, the brains of 35 young Internet addicts were scanned and analysed by researchers who found changes to the neural networks, a decrease in the volume of grey matter, and functional changes in the wiring of parts of the brain involved in decision-making, impulse control and emotions. Gunter Schumann, Professor of Biological Psychiatry at Kings College in London, came up with similar findings in a study of video game addicts. In both cases, the changes were similar to those that had been found in addicts hooked on drugs such as heroine, cocaine and marijuana.

TBSS analysis of fractional anisotropy (FA) volumes. Abnormal White Matter Integrity in Adolescents with Internet Addiction Disorder.

We learn more, more quickly

Not al neuroscientists agree with Carr and other experts who claim that the Internet is making us more stupid. “The stupidest generation?” asks Clive Thompson, a science and technology journalist and author of the book Smarter than You Think. How Technology is Changing Our Mind. His answer is no: far from making us stupid, the Internet is actually making us smarter, because it is helping us to learn more, more quickly.

In fact, when the Pew Research Center asked its panel of 370 Internet experts for their opinions on this matter as part of the Pew Internet & American Life Project, eight out of ten answered that the Internet was in fact increasing human intelligence.

Thompson believes that we are currently in a period of transition that is transforming us from private to public thinkers, in the sense that we now share our reasoning with others on the net. And he believes that this has profound, positive effects on us as individuals, on the way ideas and thoughts develop, and on how we generate ideas socially. “Now the social dimension is extremely important,” says this expert who argues that our society has thrown itself into learning to adapt to the Internet. The debate and the struggle between advocates and detractors is the same one that comes up in all technological revolutions, he says, such as the printing press and the emergence of communication media.

In response to critics of the Internet, Harvard neuroscientist Joshua Greene says it is not changing the way we think, that it provides unprecedented access to information but it has not changed what we do with it. This position is shared by cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, also from Harvard, who believes that “electronic media will not rebuild the brain mechanisms of information processing.”

Furthermore, these scientists argue that it is almost axiomatic to say that the Internet changes the brain and its processes because, as it happens, everything we do changes our brain. Every thought and every experience we have influences the constant wiring and rewiring of our neural networks. Indeed, this article is leaving its mark on your brain as you read it, as does going for a run, talking to a friend or visiting a website. This is due to a unique quality known as brain plasticity, which means that our brain cells have the capacity to adapt to our changing environment throughout our entire lives.

And given that we mostly use the Internet to search for information and to communicate, experts such as Thompson reason that the Net should actually influence our brains to be better at these things. This is probably already happening, they claim, and we are probably better at dealing with abstract information than previous generations.

Internet browsing stimulates our brains. Neuroscientists from the University of California discovered that it actually gives our brains a much better workout than reading does. Gary Small, director of the UCLA Longevity Centre at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behaviour, carried out an experiment that involved scanning the neural activity of people aged between 55 and 76, with half being regular Internet users, and the other half digital illiterates. The study found twice as much activity in the brains of those who had previously used the Internet than the brains of those who didn’t. A simple activity such as looking for information online seems to improve the activity of the circuits of the brain in adults, Small says, which may open up new forms of cognitive stimulation in seniors, to keep their brains healthy.

Meanwhile, cognitive psychologist Howard Gardner, creator of the concept of multiple intelligences, believes that the Internet is primarily an information storage space and that we are currently in the process of externalising the store of knowledge, as we already did with arithmetic calculations and calculators in the past. While we may lose some skills along the way, such as the capacity to concentrate for extended periods of time and the ability to store large amounts of information in our long term memories, the Internet is almost certainly also allowing us to develop new capacities.

Amilcar Vargas | 29 November 2013

No sabia que Socrates hubiera tenido “escriturafobia”, ahora entiendo porque lo que sabemos de él lo escribieron terceras personas. Pienso que Internet tiene ha sido una revolución tecnológica con más pros que contras, uno de los más importantes es el efecto democratizador del acceso a la información, en el que poblaciones de muy diferentes estratos sociales pueden llegar a ella y también participar de sus contenidos. Como todo cambio tecnológico tiene detractores pero en mi experiencia usando esta herramienta me ha acercado a contenidos que de otra forma hubiera sido casi imposible tener (incluyendo este interesante artículo).

Ricard Lorenzo | 29 November 2013

Porto tot el dia donant-li voltes al tema. Les tecnologies ens han canviat la vida, tenim accés inmediat a qualsevol fet que passi arreu del Món, imatges incloses, les tecnologies ens ho permeten, internet, twitter, instagram, etc., hi ha multitud d’aplicacions que ens permeten saber el que passa en temps real, estem informats, i tenir-ho al nostre abast en qualsevol moment, fa que no parem la suficient atenció, constantment surten notícies que al cap de pocs dies cauen a l’oblit, i surt un altre, i un altre,…. Això ens fa ser superficials? Potser si, peró saber aprofitar les possibilitats que t’ofereix la xarxa et permet aprofundir en temes que d’altre manera no ho haguessis fet (personalment segueixo totes les missions espacials actuals, com podria fer-ho sense internet? seria inviable per falta de temps). Ens fa ser llestos? Tampoc ho crec, l’ús de les tecnologies ens permet tenir més agilitat a l’hora de fer cerques i optimitzar el temps.

Aixó si, no ens fa falta memoritzar dades, peró per aprendre sempre farà falta una cosa: la CURIOSITAT, voler saber el PER QUÈ, aixó ens fa avançar.

Carlos A. Scolari | 30 November 2013

La última WIRED UK tiene un muy buen artículo sobre este tema… http://www.wired.co.uk/magazine/archive/2013/12

También les puede interesar… http://www.scribd.com/mobile/doc/35420872

Alba Hernandez | 29 January 2014

Internet com pràcticament tot a la vida depèn de l’ús que l’hi donis, però si que es veritat que ens ha permès una major accecibilitat a la informació A temps real, aspecte que t’ofereix la possibilitat de resoldre un dubte sobre qualsevol aspecte el instant, com per exemple el significat d’una paraula, cosa que si tinguessis que posposar a altre moment no ho fàrias. Però estic d’acord amb Ricard Lorenzo que depèn molt de la curiositat que tingui cadascún i el interès que tingui en el tema en qüestió. Altre aspecte es l’efecte democratitzador de la informació, aspecte en el que estic conforme, però no hem de oblidar que encara hi ha moltes zones tercer mundistes, i no tant, on no hi ha internet o esta betat.

[email protected] | 08 June 2015

personalmente yo he aprendido mucho desde que uso la internet pero mi uso es acerca de informacion o tengo mas opciones de aprender, gracias a esto yo considero que me ha beneficiado , pero individualmentepuece ser lo contrario si es usado especialmente como en los juegos en los jovenes cualquier persona puede addictarse si no lo usamos sabiamente

Leave a comment