“Beauty will be erotic-veiled, explosive-fixed, magical-circumstantial, or it will not be”

André Breton. Mad Love

Building the Forth Bridge, 1962. Source: Stuart Caie.

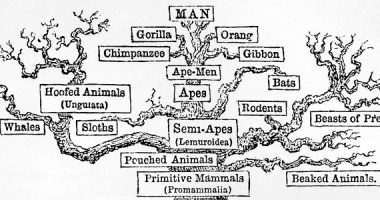

We could see the history of modern literature as a succession of resets. A series of ‘restarts’ that, as in computing and all other fields of human knowledge, would be both progressive and cumulative: tradition and innovation. Dante, Cervantes, Montaigne, Sterne, Melville, Flaubert, Joyce, Borges and Celan as engineers of complex systems, as ‘synthesisers’ of the literature and culture of their age, projecting lines of flight and of future. In each of them we find (how could it be otherwise?) poetry, narrative and essay. At the very least. All of them contain reading, rupture, and remixing of the broken pieces: experimentation (how could it be otherwise?). Nonetheless, the recurring question is not about tradition, but about experimentation. Even though literature must necessarily be an experiment, here we are again, questioning its laboratory nature.

The two poles of prose remain more or less clear: fiction and journalism. But a vast area spreads out between them, full of levels and nuances and scales and irregularities, and answering to many different names. Cultural essay. Hybrid literature. Creative essay. Travel writing. Narrative journalism. Our ‘today’ has its own cannon, its own manifold scene, just like every ‘today’ since at least Baudelaire. The current spectrum would span from the Molotov cocktail created by the mix of sociology of feelings, nonsense, cultural criticism and highbrow rap in books by Eloy Fernández Porta, to the chaotic lists that make up cultural artefacts like Alexander Theroux’s Primary Colors, novels like David Markson’s that are driven by poetics rather than by plot dynamics, Philip Hoare’s Sebaldian narratives, the political gonzo journalism of Beatriz Preciado, Sergio Chejfec’s self-reflexive chronicles, and Emmanuel Carrère’s novels without fiction, to cull just a few of the thousands of possible examples. To the extent that these authors work in genres (if we must give them a name) such as journalism, autobiography or essay, they always expand or shrink them, allowing many others to enter the textual space.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2BeKoyk4Jo

It goes without saying that the essay form was born as an experiment. A very French experiment –with Montaigne, Rosseau, Diderot– subject to autobiographical pressure and to theories of humours. And to the humour of Sterne and of other islanders. And to the ego of Thoreau and of Sarmiento. But I would argue that its most fertile contemporary aspect came about in its encounter with the social sciences. I am thinking of two books, both French, in which this encounter was particularly fruitful. The first is Breton’s Mad Love, where poetry meets psychoanalysis, which can be considered literature and even social science, but not medical science. The second is cited by Kapuscinski when he charts his own genealogy: Tristes Tropiques by Claude Lévi-Strauss, as the foundational text of a tradition that takes us through Chatwin, Sontag, Nooteboom, Magris, Morris and Sebald, and up to the twenty-first century. All of these authors are eminently narrative. They all engage with postmodern ethnography –in an explicit or secret dialogue–, the academic discipline that most closely resembles journalism, and in a modulation of geography and history through an extremely personal appropriation.

I call it a ‘text’ because this is how Richard Kapuscinski refers to his own chronicles. The author of The Shadow of the Sun also talks about ‘collage’ He insists on the necessary mix: ‘I don’t ask myself about the purity of the genre –in the traditional sense–, be it journalism, essay or poetry,’ he writes; and in one of the excerpts in the compilation Reporter’s Self Portrait, he adds: ‘My efforts are geared towards the “essayisation” of journalism’. The only thing he doesn’t contemplate is fiction. This Polish writer, like Morris and Chatwin, adds the elements of reasoning and the development of ideas to his work. Nooteboom, Magris, Sontag and Sebald, do the opposite, but with similar results. The area of convergence is one of the most fertile in contemporary literature. It comes as no surprise to find in all of them the ghost of Walter Benjamin, one of the links between Breton and Lévi-Strauss, between Surrealism and contemporary thought, an author whose texts are an incredibly potent mix of autobiography, philosophy, quotes and travel. One last quote from Kapuscinski that defends this legacy: ‘Nowadays, any book that revolves around contemporary life can only be an open text (…). We have to get used to the idea that we write unfinished books.’

But even so: the shelves of bookshops are full of non-fiction books that are born, grow, reproduce, and –with a final chapter of conclusions– die. Books that are well rounded and emphatic, but lack literary ambition. They are also generally referred to as ‘essays’, the noun accompanied by qualifiers such as ‘educational’ and ‘academic’. Let’s not kid ourselves: these books make up 99% of today’s output. The true essay, the non-conformist, experimental essay that seeks new ideas and new forms at the same time, is still the minority, the ‘avant-garde’. While the word ‘avant-garde’ refers to radical art, its Spanish equivalent, ‘vanguardia’ has two additional meanings: the military vangard, and also ‘the place on a river bank or shore where the construction of a bridge or a reservoir begins.’ I can’t imagine a better metaphor: a bridge or an aqueduct under construction; a tentative, daring, potent attempt to connect two or more shores that had, till that point, been separated. A new route between semantic fields, between ideas, between languages.

Philip Hoare’s Leviathan or the Whale, begins like this: ‘Perhaps it is because I was nearly born underwater.’ And ends with the essayist swimming alongside a whale: ‘Black neoprene and grey blubber.’ Between these two autobiographical moments, the book in turn becomes a marine biology handbook, a history of the relationship between men and cetaceans, a book about the mores of fishing, a biography of Melville, a text analysis, a travel book. In reality, it doesn’t end with those lines of text but with two black and white photographs: one of the tail of a cetacean, and one of the same huge animal underwater. Although the limits of the book are respected, the document expands. It becomes visual. It reminds us that its contemporary forms also include artistic installations and transmedia projects. It summons them up, it takes them into account. Aware that the essay will be avant-garde, experiment and laboratory, or it will not be.

Leave a comment