Nun walking in the snow | Willem van de Poll, Nationaal Archief | Public domain

It is not always easy to review the cultural legacy of women from the distant past. The chain of transmission is often broken, and the knowledge relegated to the margins of specialised research. Hildegard of Bingen, Herrad of Landsberg and Christine de Pizan are just a few examples of this heritage that must be recovered and passed on.

The German philosopher Ernst Cassirer considered that great creative works are truly great when they contain within them the capacity to inspire subsequent generations. The cultural artefact is the bridge by means of which two creators establish a connection and a transhistorical dialogue. In this way, a book, a work of art, a musical composition or any phenomenon that produces a cultural legacy is always alive as it transmits a creative force and projects it into the future.

It seems that the writings, ideas and imaginations of women thinkers across the ages, especially those that have endured in the collective memory, participate in the aforementioned chain of inspiration. Alongside the search for women pioneers and role models in all fields – who continue to be a significant source of encouragement for the women of today – there can also be seen to exist a desire to discover and explore the women who went before us.

The first reaction on discovering the philosophical, spiritual and creative footprints of women of the past is usually a bittersweet feeling of surprise and admiration, of disillusionment and disappointment. It arises when contrasting the hegemonic narrative with specialised research. Each new generation must face this transitory state of perplexity due to, among other things, the shortcomings of the educational system. Thus, we constantly return to a near-zero point which prevents women from being spared the initial shock of considering themselves valid in every sense of the word.

Another issue to deal with before discussing the women authors themselves is the fascination that mysticism currently inspires in the Western world. At the height of our consumerist society – based mainly on the acquisition of goods – capitalism is transfiguring materialism into a reality of an essentially different nature: information (“non-things,” in Byung-Chul Han’s terms) and the metaverse or virtual reality. Far from being eradicated due to the devaluation and loss of the object, capitalism exponentially accelerates its reproduction. Many digital products have a minimal production cost and can be traded an infinite number of times, significantly increasing the profit margin. After all, matter is heavy, and data moves faster.

What is the meaning and role of mysticism in this context? Mysticism has kept resurfacing throughout the course of Western history, but we must still ask why such knowledge should be of interest to us now. The answer to the question is enormously complex and at the same time very simple. Given that the dematerialisation or virtualisation of reality is a process of abstraction of that which is real, open to the innumerable potentialities of being, if humans continue to turn to mysticism, it is because they understand it as an inner root that directs them towards the truth. This is one of the definitions of mystical consciousness provided by Evelyn Underhill, a renowned scholar of Christian mysticism.

We will now delve into the philosophical, spiritual and creative universes of some European women authors of the 12th-15th centuries to find out what those “dear old ladies” (to borrow an expression from the title of the magnificent performance by Maria Gimeno) still have to say to us women of today.

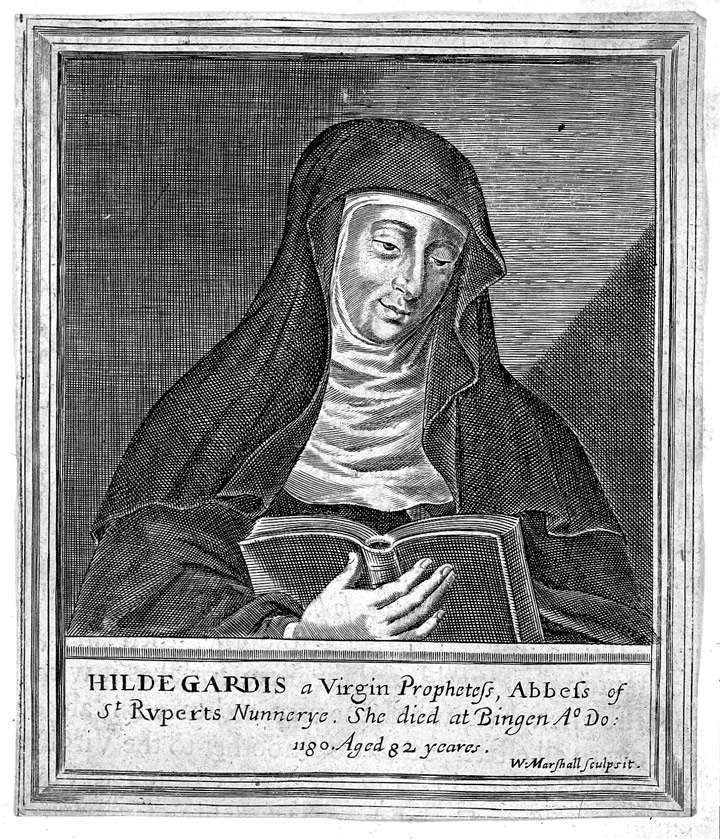

Hildegard von Bingen | Wellcome Collection

Probably the most important medieval woman thinker is the Rhenish magistra Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), author of an extensive and marvellous corpus, visionary, prophet, exegete, preacher, theologian, philosopher, botanist, poet and composer. The illustrations of her manuscripts, with their innovative iconography, show great originality and beauty. Her Byzantinesque musical pieces place her as the most prolific composer of known authorship of the Middle Ages, as asserted by the musicologist Margot Fassler. She is one of the most studied medieval thinkers, and one whose work has been most translated into several modern languages, something that is revealing.

The medical books Physica and Causae et Curae, which set down in writing the oral tradition of Benedictine medicine, and Hildegard’s music are two channels through which we have received her legacy. For me, her “scientific imagination,” as Edward Grant put it, is conveyed to us with strength, as Hildegard uses her intuition and imagination (two faculties of the mind essential to science) to make sense of certain functions of the universe. Furthermore, she indicates that we humans must try to understand nature in depth in order to grasp the “usefulness” of each being of which it is composed, so as to care for our body and soul and keep them in good health.

From reading the books available to her (the names of which we do not know, as he does not mention them) and from her own visionary reflections, she described in detail the constitution and functioning of the cosmos. She conceives of the universe as a divine creation in which the human being is placed “as at a crossroads,” a symbolic representation of decision-making. According to Hildegard, homo is not exactly free to choose, but their mission is to find the right decision in order to set their soul on the path to salvation.

In this philosophical context, the fact that a woman writes homo (“human being,” not “man”) reveals a dignification of the female condition. It is not anecdotal, since Hildegard depicts powerful female figures in numerous passages of her work. For example, “fiery life” and “the invisible life that sustains everything” are expressions she uses to speak of the female figure of Charity, which she identifies with the Holy Spirit. For Hildegard, this Person of the Trinity expresses the feminine dimension of divinity as a creator and sustainer of life.

The abbess and Augustinian canoness Herrad of Landsberg (c. 1125 – 1195) was the author of the Hortus Deliciarum, or “Garden of Delights”. Known as “the treasure of Alsace,” the manuscript included a wealth of texts, miniature illustrations and songs with musical notation. Of this codex, which was lost in 1870 in a fire at the library of the Temple-Neuf in Strasbourg during the Franco-Prussian war, only a few fragments and images survive. Although it is a pale reflection of the original Hortus, the facsimile gives us an insight into the characteristics of this enchanting 12th-century theological and encyclopaedic treatise, as well as the monastery where it was produced.

Due to its location in an isolated area high in the Vosges mountain range, Hohenburg Abbey was rarely visited by men, leaving the communal life and the task of teaching to the women. Herrad makes almost no reference to divine inspiration and has more scholarly interests than the rest of her contemporaries. Some of the unique aspects of the Hortus are its explicit mention of philosophy and the liberal arts, as well as scholastic works and those by pagan authors from the classical tradition, including Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. When we study the Hortus, some of the most deeply rooted clichés about medieval female monasteries, of which even today relatively little is known, fall away.

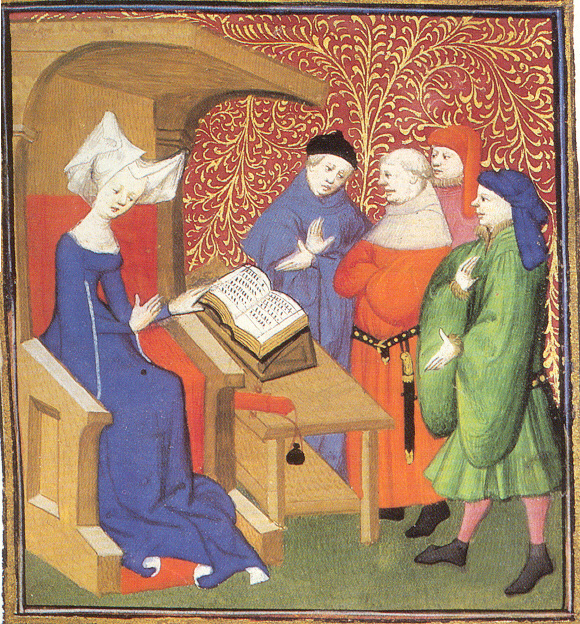

Christine de Pisan | British Library

When reflecting on the soul and its capacity for politics, the Greek philosopher Plato considered that both men and women in whom the rational dimension of the soul predominated would be fit for the task. However, his approach was a far cry from equity as we understand it today, and also from the courageous proposal of Christine de Pizan (1363-1431), a brilliant French thinker of Italian origin who imagined a city designed, built, inhabited and governed by women: The City of Ladies (1405).

In a dream, with the help of the Ladies of Reason, Rectitude and Justice, Christine builds this city by means of an argumentative dialogue and examples of notable women. From the opening pages of La Cité, we realise that many of the demands made by women are still being made today somewhere in the world. Christine also points out the urgency of using the basic political tools of mediation and jurisprudence to achieve social peace. This book questions us through a sorority or sisterhood between women and female authority. Although in today’s world, structures often have more power than the people who fill them, De Pizan’s book makes a nod to the repercussions of women’s access to places of power.

Women’s authority and autonomy are current topics. Proof of this is that one of the hot debates, that of consent, analyses how a woman’s “no” is constructed. Gender-based violence is also approached from a historical perspective even in the mainstream. Rosalía draws on an anonymous 13th-century Occitan text, Flamenca, to talk about toxic relationships in her album El mal querer (2018). Christine de Pizan deals with the experiences of women when they can freely follow their desires and develop their capacities to the fullest, as many “coaches” also do on social media.

The present maintains a living dialogue with the past. By reclaiming women’s cultural legacy, we can unravel the selvedge of the dominant narrative and allow other stories within history emerge. European women’s stories are just a few of these, but there are still countless numbers to be researched, written and transmitted.

Leave a comment