Nenes rentant-se les mans al racó de la neteja. Georgia, 1939 | Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress | Domini públic

From the digital environment a considerable number of African tools are being deployed to fight against the spread of the epidemic. In all fields, activists, entrepreneurs, and users of African social media networks are putting their ingenuity and creativity at the service of containing the disease. In the face of the global crisis, the experiences being promoted from the African continent are aiming to construct autonomous and endogenous responses, reinforce the capacity of communities to act for themselves, and propose imaginative solutions that are adapted to their particularities and their needs.

Right now, COVID-19 prevention tips generated in dozens of African national languages, perhaps in hundreds of these languages, are circulating around social media networks and instant messaging platforms. The Internet commonly appears as an instrument of cultural homogenization. This is no surprise, when 59.7% of website contents are produced in English and the 10 languages with the highest presence on the Internet total 89.3% of those contents. However, in this case, we are not talking about the survival of languages, nor about cultural impoverishment, but about understanding messages that may spell the difference between dying or surviving.

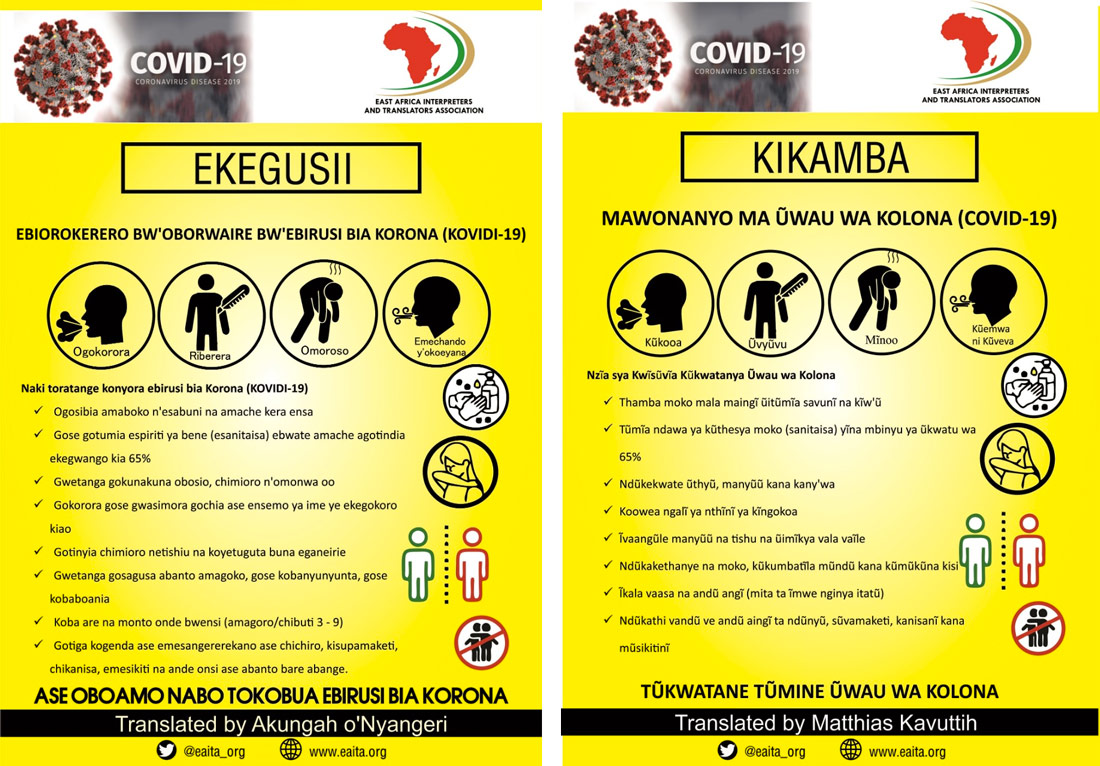

A myriad of social organisations saw things clearly as the threat of the pandemic approached the continent. This time, awareness-raising had to reach every little corner, and for this, digital tools and national languages were essential accomplices. Posters designed for those unable to speak the old colonial languages, videos produced to make advice more understandable, and even audios aimed at people who cannot read or write, or contents conceived to be distributed across not only social media networks but also messaging platforms and other private channels. Grassroots activists and organisations have been the first to respond to this need, with the tendency has also been adopted by international organisations and the authorities.

One Kenyan organisation of translators has shared a collection of posters featuring prevention measures in around thirty East African languages. A group of Nigerian doctors is sharing a video in which basic advice is transmitted in a dozen languages spoken around the country. We can find another video from Uganda that recommends staying at home, in sign language; or materials via which the JamiiForums leaks website has posted advice in Swahili, taking advantage of its large audience.

Posters featuring prevention measures in East African languages | Twitter

One of the first consequences of this deployment of digital tools in the fight against COVID-19 on the African continent was integration, because awareness-raising was the initial concern. This desire for integration, which was materialised first in the challenge of making the messages reach every corner, has also been deployed as an alternative way of maintaining contact with the community when measures such as lockdown, curfews and those that restrict movements started to spread. The social media networks have started to provide a base, on the African content too, for this need to share and exchange information with other members of the community.

In another sense, the continent’s digital ecosystems are seeking solutions. Beyond awareness-raising, information, and prevention, they are trying to generate specific responses to the new needs that the crisis is making evident. The clearest example is that of the restless communities of African makers who have jumped into the race to produce a low-cost respirator that, at least in cases of emergency, will resolve the lack of this type of equipment in the continent’s health systems. The COVID-19 crisis has led to a global shortage of certain types of healthcare materials: demand for protection equipment from nearly all countries, for citizens and health-workers alike, has unmasked the market’s most inhumane face: exorbitant prices and abusive conditions, which some meagre budgets cannot afford.

Faced with these conditions, the African technological craftspeople have unfurled banners such as Do-It-Yourself (DIY) and Do-It-Together (DIT). Seeking solutions with the materials and resources that they have to hand, they are pursuing the definitive design for a respirator adapted to their needs and possibilities, while designing automatic devices for hand-cleaning and producing protection visors for healthcare staff until their 3D printers are worn out. They are doing this in Ouagadougou, in Bamako, in Dakar and in Cotonou, in Aba, in Yaoundé, in Kinshasa and in Johannesburg.

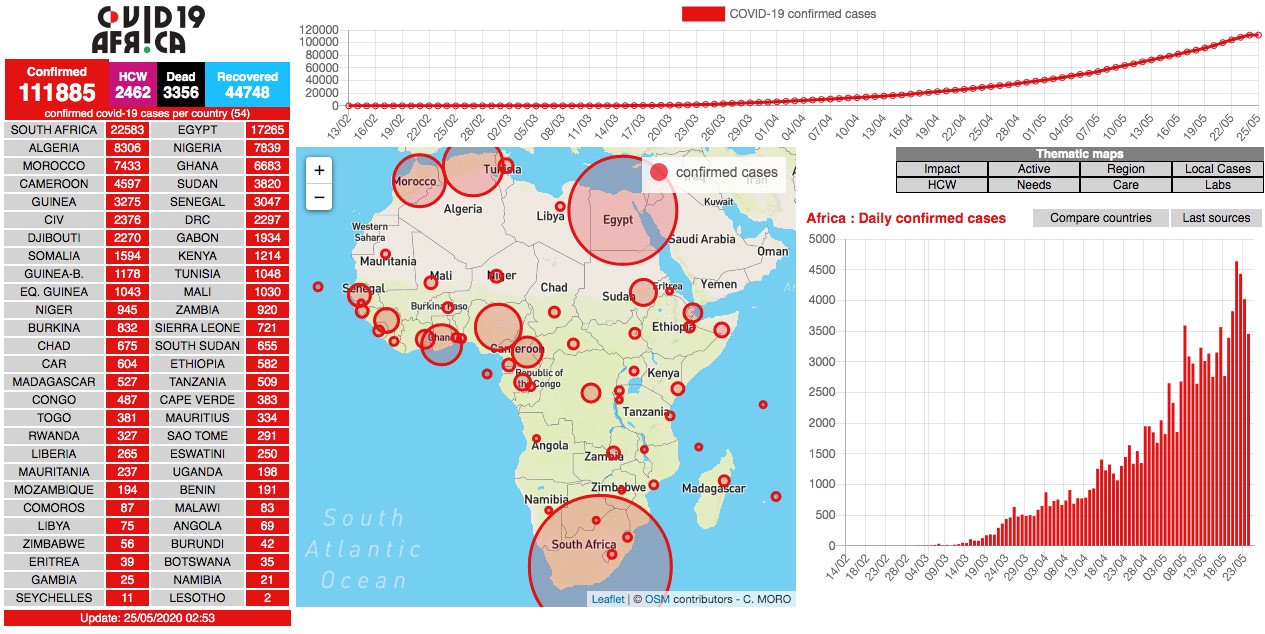

Entrepreneurs and digital activists have also deployed solutions from the field of computer programming, launching websites to follow the pandemic figures in real time in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in Senegal, in Djibouti or on a continent-wide scale. They have activated chatbots to disseminate information about the epidemic, such as Covid19 HealthAlert, developed in South Africa by Praekelt.org and adopted by the country’s government. And they have thought up all kinds of apps, whether for self-diagnosis or like that which, for example, has been launched by Nigerian company Wellvis, as well as for tracing the contacts of those infected on public transport in Kisumu County in Kenya. In some cases, such as that of an initiative also launched in Nigeria, IT apps are being adapted for basic telephones, without Internet access, and to be used in national languages such as Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo.

Pandemic figures in real time in Africa | COVID-19 Africa

These experiences show the second pillar of the use of ITC in Africa in the fight against the pandemic: the building up of autonomy. On this occasion, each country has embarked more than ever on its own crisis, despite the declarations of some political leaders, which seem more like smokescreens. Broad social sectors consider that African countries will have to tackle the situation with their own resources and skills. And many of these sectors see an opportunity to demonstrate with pride their capacity to generate these endogenous responses that the maker communities are defending.

However, the digital environment also provides a breeding ground for risks and threats. Although it seems paradoxical, the same logic of protection of others that favours the dissemination of prevention advice, is one of the fundamental components of the spread of fake news. The WHO has qualified the COVID-19 crisis as an infodemic and because of their particular conditions, citizens of the African continent are especially exposed to this plague of disinformation. One of the goals of exchanging awareness-raising messages is to ensure that they reach loved ones so that they stay safe. When the message is that COVID-19 can be prevented by drinking a lot of hot water and eating ginger, garlic or pepper; or that the virus is killed by sniffing the steam from cooking orange, lime or lemon peel, garlic, or onions with salt, many users with good intentions aim to get that life-saving information to the people that they love most. For this reason, fact-checking platforms, authorities and communities of cyber-activists have reacted immediately and are devoting great efforts to calling out these hoaxes which, in some cases, can even turn out to be lethal.

The same role of protection of the community that the digital environment is playing to defend it from misinformation is also evidenced in the use of social media networks to denounce the violence with which the authorities have on occasions imposed curfews or lockdown measures, as has happened in Nigeria or in Kenya. The reaction of citizens in the social media has also been to respond to other aggressions linked to the pandemic, such as the comments of doctors who, in a debate on a French television channel, frivolously discussed the possibility of testing vaccines against COVID-19 in Africa; or some racist episodes that have taken place in China in recent weeks against African citizens and that have provoked reactions from users from different countries around the continent.

Thus, the digital environment, within the context of the fight against COVID-19, is playing a role of cohesion within the community and enabling citizens to take the spotlight, through the already-mentioned functions of integration of a greater number of members into information and awareness-raising flows, of autonomy in the development of an endogenous response and of self-protection of the community, both when the risk occurs in the digital environment itself and when it echoes a threat that is developing in the world outside.

And in the midst of this crisis and the multiplication of experiences through which the digital environment is helping to fight this pandemic, the need is becoming more evident than ever to re-think the importance of Internet access, beyond its interpretation as a luxury service. The Kenyan government has finally allowed the balloons from Google’s Project Loon to fly over its territory in order to improve connectivity; activists have rebelled against the proposal to levy a tax on telephone recharges in order to raise funds for healthcare systems, by reminding people that it would only jeopardise the more modest classes; in Kenya and Rwanda, the promoters of BRCK believe in the right to Internet access and so are promoting the Moja Network, a free wi-fi network especially designed for rural environments, and faced with the crisis they have increased its cover and channelled educational information on COVID-19; meanwhile the grassroots organisation Internet Sans Frontieres has launched an international campaign demanding that, in Africa, the Internet be free of charge as long as the epidemic lasts.

Leave a comment