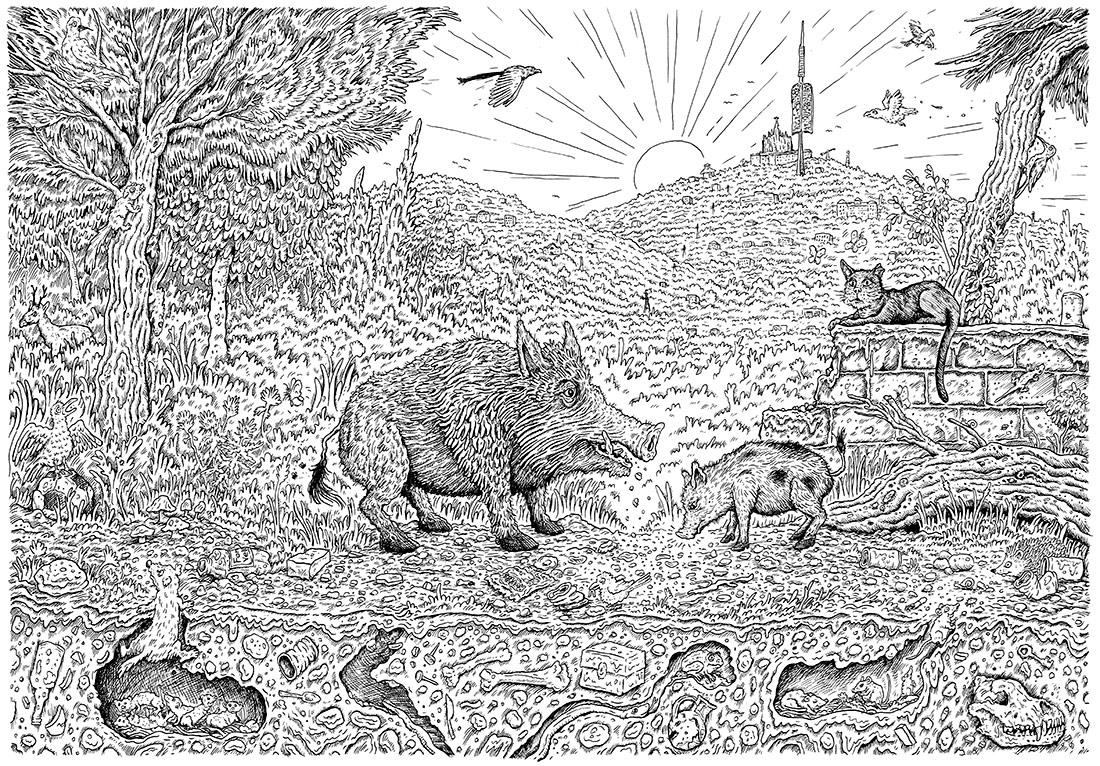

Illustration by Evin Collis

In recent decades, the idea of a domesticated, streamlined city dominated by concrete and glass has begun to be phased out. However, alongside the attempts to rewild Barcelona with super-blocks and green corridors, there are certain “neighbours” who have thrown up challenges to this push for technical control over the way in which we reconcile urban life and nature. These neighbours are wild boars – long-time inhabitants of the Collserola park – who are now proposing a reimagining of the city in a way that may be less orderly, but which is certainly more creative.

In recent years, wild boars and crosses between wild boars and feral Vietnamese potbelly pigs have become part of everyday life in those neighbourhoods of Barcelona and Sant Cugat that lie within the Collsolera Natural Park. To understand this process, one needs to know a little bit about the area’s history and ecology. The explosion of the wild boar population has been profoundly affected both by the biological characteristics of the region and by the socio-economic dynamics of recent history. During the 19th century, the shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy led to a progressive depopulation of Collserola. Emigration to the city meant the disappearance of livestock enclosures and the spontaneous reforestation of some areas previously used for agriculture. In the absence of wolves and bears, which had been hunted to extinction in the region, wild boars also had no natural predators, which helped them to spread rapidly throughout the area.

As a continuation of Ildefons Cerdà’s urban development plan at the end of the 19th century, the “Greater Barcelona” project involved the annexation of several neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city. The result was a progressive, residential urbanisation of Collserola, a trend that has been accentuated in recent decades by spatial and demographic pressures and by the increase in property prices in central areas of the city. It is within this context that Collserola has been repopulated as a residential area. This has brought with it rubbish bins, gardens and feeding points for colonies of feral cats – i.e. food resources that are very attractive to wild boars, leading to a dramatic growth in the wild boar population in recent years. While technicians and local authorities put the threshold limit at around 500 animals, estimates indicate that the true number of porcine neighbours roaming the peri-urban area is around 2,000, with significant incursions into the city centre.

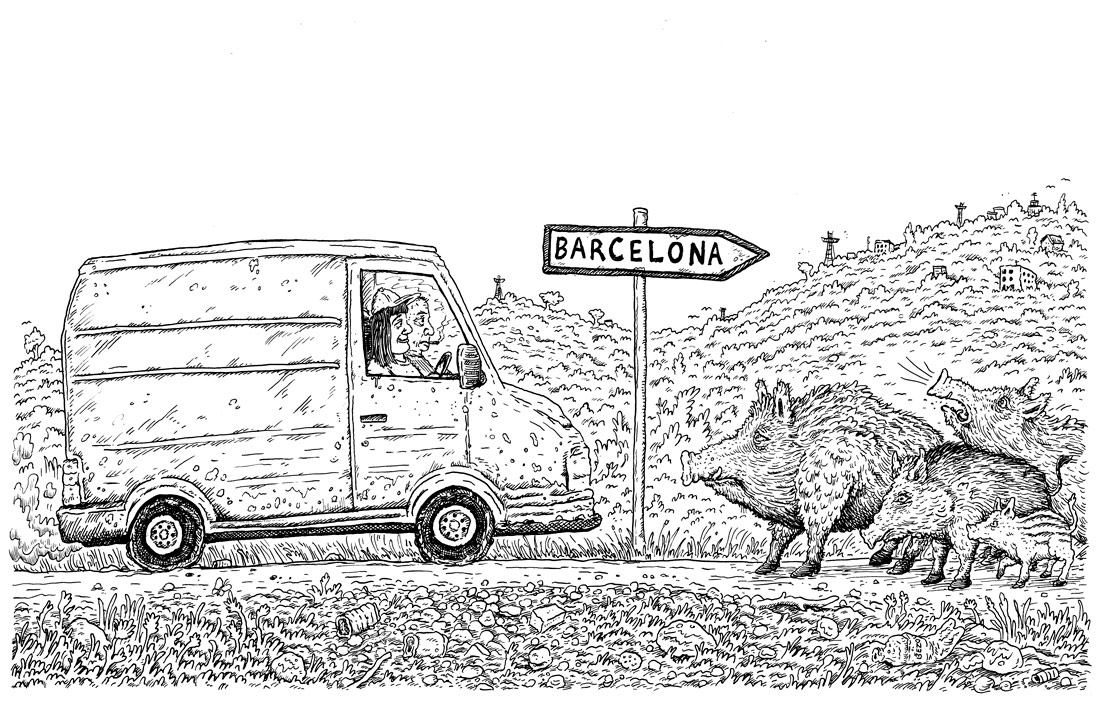

Illustration by Evin Collis

Dealing with the Porcocene

Instead of holding our heads in our hands and bemoaning this undoubtedly anomalous socio-ecological situation, we can take advantage of the circumstance to ask ourselves whether, after all, thinking about Barcelona from the perspective of a wild boar might be of any interest . Firstly, adopting a porcine perspective could help us to de-anthropomorphise the city and acknowledge that we are faced with a situation in which – whether we like it or not – non-humans are expressing (and to a certain extent materialising) their own plans for urban existence. We could say that the brazenness of these animals, which show up in parks, streets and other public spaces, gives us a reality check.

If we acknowledge this reality, we are confronted with the fact that we have never been fully separated from the wilderness, not even when we trusted in the supposed hygienic isolation, domesticity and protection offered by modern cities. Wild boars confront us with the socio-ecological reality of the time in which we are living. In fact, the presence of wild boars in the city is not only due to local causes, such as access to human-generated food sources (rubbish, people who feed them). The wild boar is a species that, due to its metabolism and reproductive rate, proliferates in line with the rise in average winter temperatures. In other words, these animals are also the result of our global warming. We could call this time – so greatly impacted by humans at various scales – the “Porcocene.” In the Porcocene, a wild boar is not only a neighbour but also an urban heuristic; in other words, a lens through which to reimagine the city in alignment with the social and ecological crises in which we are immersed.

In recent years there has been a proliferation of creative names to rethink the era in which we live. The idea of the Anthropocene emerged from the field of climatology and the realisation that the official name for our current geological period – the Holocene – does not do justice to the impact of humans on the planet. Some social scientists, such as Jason Moore, have observed that, in fact, just a small group of humans are responsible for the ecological crisis, and the root of the problem could be more accurately defined by the term “Capitalocene.” Authors such as Anna Tsing have suggested the idea of the “Plantationocene” as a way to highlight the colonial history that set us on the path to the massive, systematic exploitation of humans and nature. Predictably, there were those who, astonished to see how a microorganism called SARS-CoV-2 could suddenly turn our world upside down, proclaimed the start of the “Virocene.” But the most creative proposal is undoubtedly that of the biologist and philosopher Donna Haraway who, inspired by the long legs of the spider Pimoa cthulhu, suggested the name “Chthulucene” to think of this moment with a “tentacular” and systemic logic.

To add to this explosion of terminological creativity that seems to arise from a desperate recourse to poetics in the face of a global crisis, we can play – albeit conceptually and with a certain irony – with the idea of the Porcocene. The Porcocene is a time when pigs, and specifically wild boars, boldly roam into contexts supposedly under human control, such as cities. The incursion of the wild boar into the urban setting is often understood as a local anomaly that highlights the problems of a naïve and overly animal-friendly ecological culture. However, we could instead consider the Porcocene as a situation in which wild boars and humans are exposed to each other and experiment riskily, and sometimes virtuously, with forms of relationship born from spaces that are being progressively and irremediably counter-domesticated.

Illustration by Evin Collis

Towards an infra-species cosmopolitanism

It seems that our logic of exploiting the natural world is boomeranging back at us, and various elements (animals, microorganisms, atmospheric phenomena) are now showing their agency and marking the limits that we have hitherto failed to see. As a result, we are heading towards a dynamic of counter-domestication in which humans no longer have absolute control over our environment. The COVID-19 pandemic was a good example of our vulnerability to the action of beings that are small but “wild” or, at the very least, very difficult to tame (incidentally, Barcelona’s wild boars took advantage of this vulnerability and became quite visible during the lockdown).

Faced with this situation, there are two options. One is to persists in our drive to dominate and subjugate nature so that it may continue to serve the interests of our species. The other option is to recognise that we are far more fragile than some people imagine, and that we could, perhaps, move from a position of “domination” to one of “negotiation” with the other organisms with which we inevitably coexist. If we were to take this second approach, specifically focusing on the issue of wild boars in Barcelona, we could think of the city from the perspective of an infra-species cosmopolitanism.

By infra-species cosmopolitanism I mean, firstly, a politics of urban coexistence in which the inclusive spirit of cosmopolitanism is not limited to coexistence between humans, but also encompasses other species. Secondly, however, it is a coexistence that seeks to free itself from the categorisations of modernity, not only in terms of race, cultures or nationalities, but also in terms of species. Infra-species cosmopolitanism would respond to the reality of how relationships are woven in practice between subjects (not between species) – subjects who recognise themselves as unique, singular and autonomous interlocutors, even when this autonomy makes them deviate from the canon of habitat and behaviour ascribed to their species.

Infra-species cosmopolitanism is (quite deliberately) not “multispecies.” By analogy, a multispecies cosmopolitanism would be constructed with “multiculturalism.” It would not, however, be a question of “inter-species” relationships, just as conventional cosmopolitanism has never really been about “inter-cultural” relationships. Rather, it would be a multi-subjectivism that would imply a fundamentally “infra” perspective (infra-cultural, infra-species, infra-urban) – one that would make it possible to construct a city by boring underneath the conventional classifications, creating an emergent, imperfect city, open to the autonomy of the wild and to the indeterminacy and idiosyncrasies of the human and non-human subjects that compose it.

These ideas may hark back to the dreams of anarchist utopias that have also marked our history (the history of Barcelona). But the truth is that infra-species cosmopolitanism is not a political agenda for a project in the pipeline, but the way in which right now – whether we like it or not – boars and humans are already self-organising to rebalance their daily lives in the context of the Porcocene. You need only walk around Collserola to understand that the residents of its “hillside” neighbourhoods know how to relate to these animals as individuals who, like their human neighbours, have their own particularities. The name wild boar, said the great expert Obelix, comes from the Latin Singularis porcus. Some argue that this refers to its condition as a “solitary animal,” but it seems much more appropriate to understand it as a reference to a “singular” animal – a porcine singularity that serves as a model of an undomesticated sociability made up of subjects that rebel against any attempt at classification.

Leave a comment