International Motor-Cross Grand Prix 1963 in Markelo. 1963 | Dutch National Archives. Wikimedia | Public Domain

Petro-masculinity is neither a new nor an isolated phenomenon. Motor culture has always turned around an eminently masculine imaginary. With the industrial revolution, machines quickly became associated with masculinity, and the noise of industry became a symbol of strength, progress and dominance over nature. Petro-masculinity and its practices perpetuate this machinist hyper-masculinity that gives man control over means of production and the administration of noise. The noise of petro-masculinity can be heard as the announcement of a disturbing acclamation of accelerationism and a dangerous smokescreen that turns its back on the many challenges that society urgently has to face in the fields of sustainability, equality and affectivity.

The velocity, violence, magnitude, and horrible noise of the engine give universal satisfaction to all beholders, believers or not (…). The noise seems to convey great ideas of its power to the ignorant, who seem to be no more taken with modest merit in an engine than in a man.

James Watt (Letter to Matthew Boulton, 1777)

Nous nous approchâmes des trois machines renâclantes pour flatter leur poitrail. Je m’allongeai sur la mienne… Le grand balai de la folie nous arracha à nous-mêmes (…) et voilà tout à coup que deux cyclistes me désapprouvèrent, titubant devant moi ainsi que deux raisonnements persuasifs et pourtant contradictoires.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (“Le Futurisme”. Le Figaro, 1909)

The lockdown decreed in March this year had as one side effect a drastic reduction in environmental pollution and noise density in public spaces. One of the first noises to re-emerge and disrupt the unprecedented serenity of the post-quarantine soundscape was that of the exhaust pipes of cars and motorcycles, both powerful and mechanically modified to increase the volume of their acoustic emissions.

These noises, however, had ceased to be that old fleeting annoyance, resignedly endured, to become a disturbing and literally accelerationist statement of intent. In the context of an unprecedented social crisis, the premeditated amplification of the noise produced by the combustion engine seemed laden with obscure new connotations, and its imposition on others resonated, more than ever, as an anachronistic authoritarian provocation.

Masculinity, fossil fuels and authoritarianism

The noise produced by this type of driving, executed with a performative intention by drivers—in almost all cases men—is precisely what Cara Daggett refers to as petro-masculinity. In her article “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire”, Daggett explains how fossil fuels are often used in authoritarian practices involving certain male sectors. One such is known as “rollin’ coal”: modifying a diesel vehicle (usually a 4×4 truck) to increase the amount of fuel injected into the engine and thereby produce great plumes of black smoke through the exhaust pipe.

Beyond its absurd recreational nature, rollin’ coal has become a form of protest and ridicule of environmental discourses and warnings about climate emergency. YouTube has countless videos made by the fans of this practice to record the harassment to which they subject drivers of hybrid vehicles, Asian makes of car (“rice-burners” in their slang), cyclists, ecologists and protesters who oppose the policies of the Trump administration. The protagonists of this ejaculatory celebration of diesel combustion—also known as “pollution porn”—are always white men, and their smoke attacks often take the form of sexist, misogynistic contempt.

Petro-masculinity is neither a new nor an isolated phenomenon. As many car ads show, motor culture has always turned around an eminently masculine imaginary. In their advertising messages, the woman (or, rather, the image of the woman) appears as a secondary element or an object of passive desire available to men who are rendered attractive by the irresistible characteristics of the vehicle advertised. Similarly, the women responsible for presenting the trophies in motor and motorcycling competitions have traditionally been objectified and presented as though they were part of the prize for the driver of the fastest, most powerful vehicle.

This sexist bias also pervades a whole host of products of contemporary popular culture. The most flagrant example is Fast & Furious, a multimillion-dollar film franchise that for two decades now has been perpetuating the stereotypical equivalence between fuel power and masculinity. You only have to watch one of its trailers to see the hyperbolic testosterone intensity concentrated in the films in this saga starring Vin Diesel (his artistic name couldn’t be more appropriate) and some of Hollywood’s most hypermuscular actors.

According to Daggett’s analysis, petro-masculinity is a variant of hypermasculinity that draws on a “catastrophic convergence”, to use Christian Parenti’s term, of three factors: evidence of a climate emergency that calls for urgent action, a fossil fuel-dependent economic system that is doomed to collapse (“fossil capitalism”, to quote Andreas Malm) and a historically hegemonic understanding of masculinity that is showing increasing signs of fragility.

Rollin’ coal would be the most extreme example of a whole series of compensatory practices derived from the anxiety that these three factors (together or separately) may produce among certain “agents of hegemonic masculinity”. When some of these agents “feel threatened or undermined”, writes Daggett, they often need to “inflate, exaggerate or otherwise distort their traditional masculinity”.

Although drivers who modify the exhaust pipe of their vehicles do not, in principle, endorse an explicitly anti-environmentalist, racist or misogynistic discourse, the imposition on others of the noise they produce with their driving is as indiscriminate and authoritarian as the actions carried out by fans of rollin’ coal. This audible eroticism of the exhaust also seems to equate the noise of combustion in a performative, compensatory way with an inflated manifestation of autonomy, power and virility.

Noise and petro-masculinity

In her article “The Gender of Sound”, the poet Anne Carson examines the old stereotype that the female gender has a greater predisposition to verbal and sound incontinence than the male. Using a series of examples ranging from Aristotle’s considerations on women to Freud’s theories of hysteria, Carson describes how, over the centuries, the capacity for verbal continence has been considered “an essential feature of sophrosyne, that virtue that supposedly conferred prudence, moderation and self-control on men”. According to this belief, the man “should be able to dissociate himself from his own emotions and so control their sound” to avoid his behaviour being feminized.

After the industrial revolution, a new, opposing stereotype was gradually superposed over the previous, without making it disappear completely. Machines quickly became associated with masculinity, and the noise of industry became a symbol of strength, progress and dominance over nature. Verbal and auditory excesses in women, however, continued to be seen as a sign of lack of control and emotional incontinence. In 1777, in a letter to Matthew Boulton, James Watt praised the noise of the steam engine, describing it as a source of “universal satisfaction” and proof of the extraordinary power of his invention. The noise, he claimed, “seems to convey great ideas of its power to the ignorant, who seem to be no more taken with modest merit in an engine than in a man“.

It is interesting to note here that, years after the invention of Watt’s noisy steam engine, it was precisely a woman, Mary Elizabeth Walton, who was responsible for designing and patenting some of the first devices intended to reduce high levels of noise pollution produced by industry and the railway in nineteenth-century cities. A pioneer in protecting the environment and promoting healthy working conditions in factories, Walton also invented a filtration system that minimized the polluting effects of smoke by deflecting it through a series of water tanks.

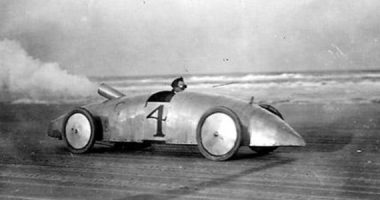

In the Manifesto of Futurism, published in Le Figaro in 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti praised the noise of the machine and described the motor car as a “snorting beast” that could be tamed if caressed lovingly on the chest. “A roaring motor car that seems to ride on machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace” reads point four of the manifest. Marinetti also ridiculed two cyclists who reprimanded him for his energetic, reckless driving. With his erotic-machinist proclamation, Marinetti anticipated the sexist messages of advertisements like the one for the Subaru GL Coupe, which compared the car to “a spirited woman who yearns to be tamed”. Marinetti’s words also foreshadowed the authoritarian exaltation of the combustion engine practised by rollin’ coal fans and drivers who modify the exhaust pipe of their vehicles to make more noise.

As Marie Thompson noted (Beyond Unwanted Sound. Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism, 2017), assigning a specific sound behaviour to a gender or any other identitary category can be problematic unless it is situated in a given social and historical context. The relation between noise and masculinity has certainly been ambivalent and changing over the centuries. Whereas, in pre-modern times, men were supposed to have recourse to sophrosyne to control the sounds derived from their emotions, after the industrial revolution the noise of the machine became an affirmative attribute of modern masculinity and a way to prove its merits.

Petro-masculinity and its practices perpetuate this machinist hyper-masculinity that gives man control over means of production and the administration of noise. At the wheel of a car or astride a motorcycle, man can maintain the hieratic attitude formerly assigned to him by sophrosyne by delegating the production of noise to a machine that acts as an appendage of his body and personality. The vehicle thereby becomes a kind of ventriloquist technology that gives the driver a “second voice” and allows him to roar without having to open his mouth or utter words.

According to Jacques Attali (Bruits. Essai sur l’économie politique de la musique, 1977), this roar is nothing but the sublimatory simulacrum of a violent and authoritarian action. “We must learn to judge a society by its sounds in order better to understand where the folly of men is leading us, and what hopes it is still possible to have”, wrote Attali. It is in this sense that the noise of petro-masculinity can be heard as the announcement of a disturbing acclamation of accelerationism and a dangerous sleight of hand that turns its back on the many challenges that society must urgently face in the fields of sustainability, equality and affectivity.

Leave a comment