Potato harvest | Wikipedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

How do we write what we eat? How do we digest texts? Do books feed us? Is cooking science? What about literature? Or are they short cuts and if so, to where? What does the food we eat and how we make it tell us about our society? What is the real history of the potato and why could we say it is more amazing than the odyssey of Ulysses? Milking our eating habits for anthropological, fictional and textual substance. Wringing out the relationship that we have with food: right down to the marrow, with the screen as a serviette.

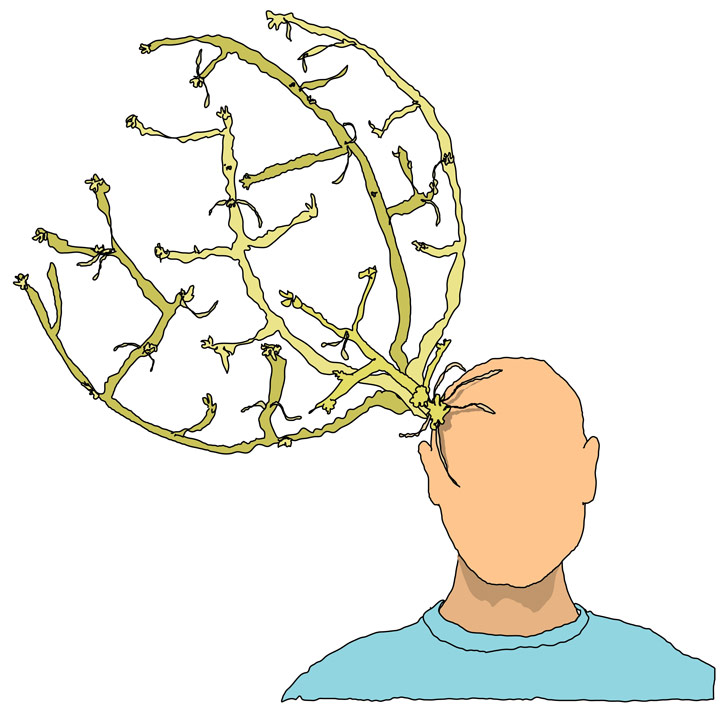

Is there a first time, an origin, a single explication, a reason behind everything? Or is it just our desire, the ignorance we display, the urge of wanting to explain everything? Questions demand an answer and the bridge they predetermine is too narrow: the whole world flows below it, fast, unfathomable and fresh and it is worth bathing in it, dipping into it, drinking from it, sprouting shoots, sprouting gills.

*

They say that it all started on a high Andean plateau. Was there one sole discoverer, a single pair of hands digging up the earth, or were they found already unearthed by a torrent of water? Were they a pile of experiments heaped together and forgotten then deposited over the course of the centuries? It seems that the sweet type came first and the other was inedible – small and twisted like arthritic fingers – and they had to cross-breed it time and again to be able to get their teeth into it. And also that they used to freeze and sun-dry them, making a dehydrated blob that could be kept up to ten years. That a great empire used them to deploy its power over the continent. That there were a thousand types of them.

Everything slips our grasp: who knows what truly happened 10,000 years ago?

Who remembers what they had for dinner last Wednesday?

Potato omelette?

Carrot soup?

Nobody remembers their first time.

Who knows when they took their first bite of a potato?

Why are carrots orange?

It’s not important. Right?

What is important?

A prince? A name? A colour?[1] A war?

Spud Crazy | © nomdenoia, 2018

The main information that a question provides is about whoever is asking it: what interests them, from where they are asking it, what they know, the kind of person they are. Every question prefigures an answer, or rather, the limitation of that answer. It’s a kind of mould: human questions give human answers, at the service of the human mind’s limited knowledge. We cannot access knowledge, knowledge in its entirety, knowledge outside the human mind, through the questions that we ask, because above all what they do is narrow it down. Questions are useful to us as a spur, but cannot be a method. They are the crutches of curiosity when it does not fly, a beginning, but they can never be what determine our research – true research discovers what it doesn’t know it will discover and has to allow itself to do so: if you find what you wanted to find, why were you looking for it? What benefit does it give you? If the aim is self-corroboration, the outlook is not good. A direct question opens nothing, it is not a key; it is rather, simply, the negative of a lock. And we don’t want to know how the door closes but rather what is beyond it. What escapes us. In contrast, questioning ourselves is not heading blindly into an answer, into the lock, but more a case of flying over the territory of our knowledge, mapping it out, widening the battlefield. Multiplying it. Making it fertile: breeding more questions, not answers. A thick web of questions that we measure, let loose over the immensity of what is not structured to be understood. Playing it, experiencing it, becoming wrapped up in it, learning not to impose the meaning. Questioning ourselves means asking ourselves bird-questions, that act like ship’s lookouts in the sky of our thought and spot undiscovered lands, skyscraper peaks and splendid clearings, without parallel. Incomprehensible. Unknown. Peaks of wisdom, dissolutions of reason, thought that is overflown and overtaken.

Spud Crazy | © nomdenoia, 2018

I don’t know how Edu and I first met. I think it was when were playing with the Sirles, a chaotic and foggy era, probably on a summer night in Sant Feliu de Guíxols, the kind of night where you end up in the sea stark naked under the stars. It’s been years since we last saw each other. We arrange to meet at half six at the temple. It has two entrances: one from the square and one from the alleyway behind. I find him at the marble bar, chatting with Josep, who is explaining how one day, with a partner of his, they locked themselves in the kitchen in order to make the perfect patatas bravas. Scientific method: various varieties of spuds, measurements of oil temperature and timing, double and triple cooking processes, et cetera. He doesn’t explain the secret to us and recommends we try the baby octopus, a true delicacy, tender and tasty. Between beers, I ask Edu if he remembers the first time he ever ate potato. He makes one of those faces that are so his, so expressive, with ambushed laughter about to assault you from every corner of his ears, his eyes and his nose. He says he doesn’t, but he imagines it must have been mashed up, in the form of purée, like so many other kids. I bring him up to date on my spud research, full of amazing anecdotes such as the Potato Edict of Frederick the Great[2] or the story of this poster[3]. He tells me that what he finds most amazing about the potato is that it is infinite. I suppose that he is referring to its capacity to sprout and sprout, not depending on a seed to continue its cycle. To germinate and graft itself here, there and everywhere. To spread out. To emerge from itself and become another. At a dinner party a few days ago, somebody brought some sparklers to celebrate the get-together and a couple of guests suffered slight burns. We were in the Priorat area. A writer friend of mine told them to cut a potato and rub it over the burn, saying it would calm the stinging and heal the skin. It worked. Why do we have to perpetuate the segmentation of knowledge? Who benefits from the distinction between theory and practice, between textbook and trials, between narrative and non-fiction? Why not practice a literature without floodgates and plant potatoes in its footnotes?

*

Turin, 1889. A man flogs his horse mercilessly. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche is overcome, he flings his arms around the animal and falls to the ground, sobbing. Crazy, he will never recover his mind. He dies eleven years later. In 2011, the brilliant Hungarian filmmaker, Béla Tarr, wonders about what happened with that horse and its owner – and his daughter – in an isolated farm in no-man’s land. This question becomes a film that offers no answer, that screams apocalypse: A torinói ló (The Turin Horse). I don’t remember when I ate potatoes for the first time but I will never be able to get that film out of my head: the incessant wind, the growing darkness, the daily struggle for survival and at the end of six days, the end of the world when, finally, they could no longer boil the potatoes that they ate every evening with their hands, father and daughter, face to face, in silence, as though in a pagan communion.

[1] Citrus fruits are twenty million years old and originated in Asia. In the year zero, in India the orange was known as “naranga”, in Sanskrit. As they journeyed west, this fruit was assimilated by the Arabs, who introduced it into the Iberian peninsula with the name nāranj and the French in the Middle Ages called it orange based on the Arabic and the Italian arancia. Since then, the fruit’s name has also become the name of its colour. William the Silent, a noble of the Nassau family, was born in Germany in 1533. When he was eleven, his cousin, René de Châlon, Prince of Orange (a county in southern France) died, and he inherited his titles and became Prince William van Oranje-Nassau. He would end up captaining the Dutch revolt against the Spanish monarchy that would set off the Eighty Years’ War, and in 1648 would culminate with the independence of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. In those days, the Dutch were big carrot-growers, and in honour of the royal house that had given them independence, they started to mass grow a very rare species of carrot containing a large amount of beta-carotene, a pigment classified as a terpenoid hydrocarbon, the same colour as the name of William’s dynasty. In other words the fruit – the orange – gave its name to the colour and the Dutch ended up giving this colour to the type of carrot that is most common everywhere today. Like the one that you grated into your salad yesterday.

[2] When the Europeans discovered the potato in America in the early 16th century, it caused no stir among them, rather the opposite: the green part was poisonous, it came from the dangerous nightshades family, it was not mentioned in the Bible and it didn’t look too good either. So when it reached Seville, it was grown in the courtyard of the Hospital de la Sangre in the year 1570 to feed the poor who were living there: if they died, nobody would kick up much fuss. Contrary to all expectations, its high nutritional value (easily digestible proteins, minerals and vitamins) helped them to recover. Felipe II saw an opportunity and sent some to the Pope, who had an ambassador who was ill in the Netherlands so sent some to him. There, the potato fell into the hands of botanist Carolus Clusius – responsible for introducing the tulip – and he planted some in Vienna, Frankfurt and Leyden. The crazy Frederick the Great would be one of the first people to understand that the potato could strengthen his soldiers and the population in general, because it was a nutritional food that could be grown anywhere, in adverse conditions and independently of harsh weather conditions that could devastate other crops. To overcome the reluctance of the peasant farmers, Frederick used two ploys: one subtle and one categorical. He had a royal potato field planted by a busy thoroughfare and put guards there to watch over it. This amazed the peasants and they started to take an interest. To ice the cake, he gave instructions to his guards to sleep at night and not be too attentive to their guard duties. It didn’t take long for people to get hold of the coveted potatoes and plant them themselves. The categorical ploy came in 1756 with the Kartoffelbefehl, or Potato Edict, which obliged everyone to plant potatoes. Their initial rejection very quickly became devotion. Antoine-Augustine Parmentier used the same ploys in France – where the potato had been banned by parliament since 1748 because they alleged it caused leprosy – by planting potatoes in the garden of the Tuileries Palace to attract interest to the cursed tuber, but since he could not hammer the point home by publishing an edict, he used other arms to make spuds fashionable: he convinced Marie Antoinette to carry a bunch of potato flowers and organised major feasts with celebrities such as Benjamin Franklin, where all the dishes were based on different ways of cooking potatoes. Eventually, in 1785, a year of failed crops, the French populace gratefully accepted the potato as a way of avoiding famine. Exactly the opposite happened in 1845 in Ireland: there, they would grow the “Irish Lumper” variety as a monoculture. With the arrival of the American pest – Phytophthora infestans, a condition that caused potato blight and wiped out the crop in the blink of an eye – in just four years the Irish population fell by two million people, of whom one million died and the other million emigrated.

[3]

Halt Amikäfer! 1950 | © Deutsches Historisches Museum

Leave a comment