Silvia Fehrmann has extensive experience of promoting educational projects and nurturing creativity and cultural exchange. She heads Artists-in-Berlin, a prestigious programme of residencies open to creators from around the world. We talk to her about how to bring cultural institutions up to date to make them public spaces with meaning and with a connection to the public.

Since she landed in Berlin from Buenos Aires two decades ago, journalist and cultural producer Silvia Fehrmann has been closely involved in the cultural life of the city. For the past five years, she has been heading the international artist-in-residence programme Artists-in-Berlin run by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and she is a spokesperson for the Berlin Arts Council. Prior to this, she worked as director of communication and educational projects at the House of World Cultures (HKW), where she launched some of the institution’s flagship programmes, such as The Schools of Tomorrow, and at the legendary People’s Theatre, the Volksbühne, under the direction of Frank Castorf. On all these fronts, she has striven to create and strengthen cultural spaces that are pluralistic, open to difference and encourage the circulation of critical thought. A firm advocate of public funding for culture, “at a time when fascism is growing,” she says that “the ability of cultural spaces to generate networks and communities is more important than ever.”

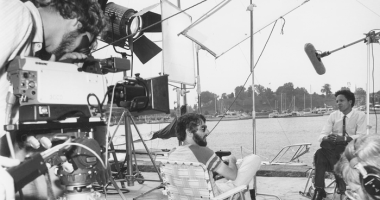

From Berlin, the cultural capital of Europe and a magnet for a large community of artists from all over the world, the programme of residencies run by Silvia Fehrmann is one of those spaces that actively promote the circulation of ideas and people and the creation of communities. Over the past sixty years, it has invited more than a thousand musicians, filmmakers, visual and plastic artists, dancers and writers to join the city’s cultural milieu. The list is very long, very long, and includes many of the great creators of contemporary culture from recent decades such as John Cage, Susan Sontag, Svetlana Aleksievitch, Jim Jarmusch, Andréi Tarkovski and Marina Abramović, to name but a few. More recently, the proramme has welcomed writers Fernanda Melchor and Samanta Schweblin and the artist Teresa Margolles, and, from closer to home, Eulàlia Valldosera, Cesc Gelabert, Antoni Miralda and Mathias Enard.

Each year, the programme offers twenty to thirty established artists the chance to live in the city for anywhere between six to twelve months, with all their needs covered and without any conditions or obligations. “Nothing drives creativity more than the invitation to have absolute freedom,” says Fehrmann, “and Artists-in-Berlin gives artists the time and the opportunity to build up symbolic capital.” After the residency, some, like Samanta Schweblin and Svetlana Aleksievitch, settle in Berlin; for most of them, the experience of stepping out of their usual surroundings and immersing themselves in another cultural and artistic life is a turning point in their career: “Moving has always been an aesthetic procedure, it allows one to develop a new way of looking at things, to break with habits, to unaccustom perception.”

According to Fehrmann, a residency programme like Artists-in-Berlin has a much more profound effect on the life of the city and on local and international cultural production than do biennials and festivals, “which do not allow for the creation of community, do not take root with local stakeholders and have no relationship with the place.” Thus, the richness of the project lies not only in its ability to promote the international circulation of people and ideas, but also, and more importantly, to generate networks and to propel the voices of artists by encouraging them to participate in the city’s aesthetic and political debates and to actively connect with local creators and institutions. “Spending half a year or a whole year in a residency allows you to root yourself in a place, and in times of globalisation this is an advantage for both the artists and the community, because these roots generate other content, other perspectives, more depth. In this sense, Berlin benefits from these international artists who contribute to the quality of what is being produced in the city in both the contemporary and classical arts.”

Artists-in-Berlin, which has nourished the city with an uninterrupted flow of creators over the past sixty years, was created by the Ford Foundation in the middle of the Cold War as a soft power strategy. It was based on a belief in the power of art to open up the city after the wall went up and to combat the ongoing currents of fascism in culture. Today, at a time when the European continent is turning in on itself and is being shaken by a new wave of authoritarian movements, programmes like the one directed by Silvia Fehrmann continue to be an act of resistance against the closing of the gaits.

Steadfastly open to the global South (the most recent residents include artists from all over the world, from Sri Lanka and Nicaragua to the United States), it welcomes a heterogeneity of origins and practices that respond to diverse institutional and cultural contexts. “Behind each individual artist there are often networks of colleagues, institutional networks, critics, thinkers or schools. Even when many of the artists settle in Berlin, they continue to be active in their home countries, generating a recirculation of ideas as well as economic recirculation. We not only promote individual artists, but by recognising individual artists we also boost the relevance and recognition of other local artists and scenes”. For Fehrmann, this is in fact one of the keys to the project: not to reproduce the values imposed by international biennials and to give prominence to artists who are important in their local contexts. “The result is that our artists then begin to work in well-known biennials and festivals and to diversify artistic practices.”

The aim is to generate networks and then communities and to bring together heterogeneous production and creation logics, connecting them with local contexts – to displace voices but also to recombine them, articulating them in other ways, generating other connections and other relationships: “It seems to me that institutions in all fields need to reinvent themselves to tackle the complexity of the current moment, and rearticulating the relationships between stakeholders changes the way we think. When interlocutors are rearticulated, new questions and new thoughts are generated.”

Fehrmann adds that “one of the roles of culture is to insist on the possibility of facing complexity without slipping into forms of cruelty; keeping these public spaces open is essential at the present time, and we must try to invite as many social actors as possible who are still on this side, on the side of democratic ideas and peaceful exchange.”

Leave a comment