Edwin Denby with megaphone at ball field, 1922 | Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

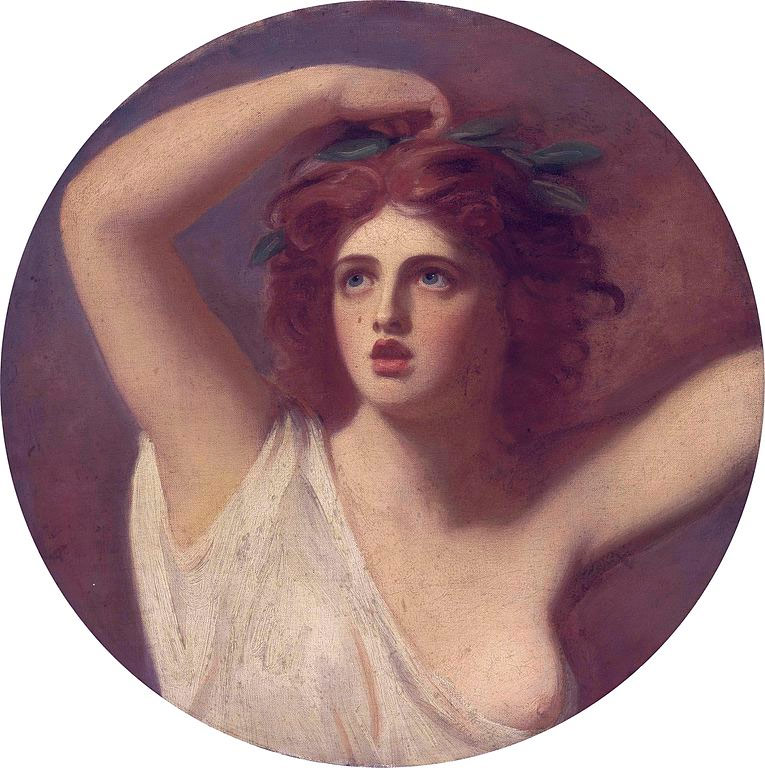

In classical mythology, Cassandra represented the curse of one who, although knowing the truth, was unable to convince her fellow citizens of it. Today, a lack of confidence in the political system and a greater presence of emotions in our decisions have led to a radicalisation of opinions. Within this context, we analyse the phenomenon of disinformation in the 21st century, where the emergence of new channels for dissemination is making us more vulnerable.

When talking about disinformation, people often talk about a series of phenomena that, despite being related with a lack of specific information regarding politics, have very little to do with this lack of knowledge per se. The fact is that lack of knowledge alone does not generate the dynamics of polarisation, lack of dialogue and mistaken perceptions of reality that seem to be marking our democracies at present. Lack of knowledge only makes us vulnerable to falling into the trap of the agents of disinformation, especially when it is combined with a mood and a context that facilitates this.

Lack of knowledge and lack of information are not, per se, a problem for democracy. At least not a problem that has a solution. For years, political experts and scholars of democracy have known that we as citizens are disinformed regarding the political questions that affect us. Politics has become a very complicated subject and it is impossible to have information about all of its dimensions. Even when we have the information at our disposal, it is hard for us to manage it correctly. This happens to us all, perhaps not always in politics but in some other area of life. I, for example, would fail any test to find out which laptop best suits my needs, or which medicine will best cure my stomach-ache. And yet, I buy computers and self-medicate without too many concerns. Making decisions in areas of life that are close to us, without having all the information that we need to do so, is an everyday occurrence. Disinformation, understood as a lack of specific knowledge about politics, is not a new problem, nor a problem that makes the functioning of democracy impossible. It is something that we have known how to live with for some time and that, to a greater or lesser extent, we deal with.

We live with disinformation because we compensate for it with mechanisms, such as the views of experts or opinion leaders. I buy computers and medicate myself because I follow the recommendations of people who do have knowledge of the field. And many citizens vote because they have a reference point that knows how to give them good indications and clues regarding which party will best represent them. Things such as ideology, a candidate’s socio-economic profile or the groups that support him or her are also elements that do not require a detailed knowledge of reality and that help many citizens to decide which citizen or party they want to vote for. Generating citizens with greater specific information on the things that are happening in politics will be unlikely to solve the current problems around disinformation. It is more important to work on the creation of spaces for heuristic signals and discourses that enable citizens to understand politics without having to know about it in all of its complexity. As Åsa Wikforss explained in her lecture at the CCCB, for the creation of spaces for dialogue one key element is needed for citizens to be able to obtain information from other humans: trust in the knowledge that others transmit to us. And here is where the problem lies, not in the lack of knowledge per se.

In this sense, a first element to take into account regarding the current situation is the lack of institutions that guarantee the generation of reliable and plural heuristic signals. For some time, political experts have viewed with a certain degree of concern how many of the signals that citizens use to understand politics have been losing relevance: social groups have gradually become weakened, ideologies have become blurred, and the socio-economic profiles of candidates have become homogenised. Many voters have been left lacking resources to be able to navigate the political debate without having to understand the complexity of each of the debates that arise. We have more information than ever within our grasp, but it is possible that it is presented in a worse way and not as easy to digest as previously. Mechanisms of simplification of information are required in messages that can be understood by non-experts.

However, the current problem is probably more complex than a combination of disorientation and lack of useful information. It is a problem that has been worsened by two elements that were the subject of much reflection by Åsa Wikforss and Adrienne Lemon in their lectures at the CCCB. There are two elements that would be added to the lack of useful information to account for the problem of disinformation, and these are elements that definitely would generate the polarisation and extremism that is observed in many of today’s democracies. Two elements that make disinformation not so much a problem of a lack of correct information that helps people to understand the world, but rather a deliberate act in which citizens have correct information but prefer to believe information that is incorrect. What Wikforss termed “resisting the evidence”. This more active phenomenon of disinformation is important because it changes the roots of the problem and makes more structural requirements necessary in order to resolve it.

The first element is a mood that means that certain types of information, which generate hate and anger, progress much more easily than discourse based on harmonious coexistence and optimism. This negative mood means that it is much easier for many citizens to believe such information that confirms their mood of anger and sadness, than information that contradicts their emotions. Emotions are a key part of managing information, they enable information to be processed and managed efficiently. They are useful when learning and acquiring knowledge. However, this interference by the emotions becomes problematic when the population are managing information from emotions of frustration and anger with the political system. Because this generates a bias that makes information coinciding with this negative vision of society much more believable and, consequently, this means that polarising discourses or violent extremisms are much easier to believe than conciliatory discourses and those promoting coexistence.

Lady Emma Hamilton as Cassandra | George Romney, Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain

The problem, therefore, is not the role of the emotions, but the fact that the dominant emotions among many people are so negative, probably for reasons that go far beyond the communication context. As explained by Lemon, management of the individual’s context and emotions is a key element in the management of disinformation. Interventions must always take into account the injustices or situations of frustration that are experienced by individuals and that lead them to be highly predisposed to believing in certain discourses. No communication campaign against disinformation can be efficient if it does not take into account the emotions of its receivers and manage them.

The second element is the appearance of agents who take advantage of the current situation of disaffection and devote themselves to break the contexts of trust necessary for information to circulate. Something that, as Wikforss explained, can be done either by exploiting trust and transmitting false information, or by undermining trust in the actors that convey the information, such as the media or governments. Both of these dynamics are self-feeding and make the accumulation of correct information impossible. These agents have probably always existed, but today’s technologies enable this information to be circulated faster and further. What were previously marginal voices in their own spaces, can now form communities that reinforce each other. This is a dynamic that can be positive in some cases but has evident risks when only used for disinformation.

In summary, despite a lack of correct and useful information being a problem that is making us vulnerable to disinformation and all of its consequences, the solution to the problem needs something more than correct information. It is necessary to work on dynamics that generate resistance to the evidence presented, both with regard to mood and to the management of trust in the sources presenting such evidence. In this sense, as explained by Wikforss and Lemon, a key element for understanding the phenomenon is the generation of identities and narratives that determine the perceptions of individuals, because it is these narratives that determine how individuals will manage the information that they receive. Working on the generation of narratives that are productive, conciliatory and tolerant, with which individuals can identify, is one of the great challenges facing current democracy if it does not want to continue falling into the dynamics of polarisation, intolerance and extremism that exist today.

Leave a comment