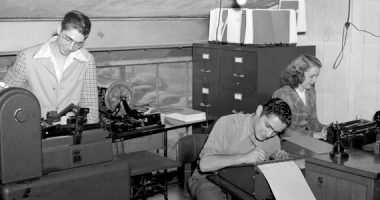

A three-year-old reader reading in a public library in Montreal, 1930-1960. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

For five hundred years, intellectual property and copyright have been the cornerstone on which a huge number of business models have been built. In the information society, with the Internet as its greatest exponent, intellectual property protection has taken on new aspects and continues to raise challenges and concerns for authors, publishers and technology companies. How should copyright be exercised and managed against this backdrop?

Intellectual property is a legal concept that has been with mankind for centuries: it began in the Renaissance, and the spread of the movable type printing press resulted in the creation of the first monopoly-based legal framework for printers. The intellectual property system as we know it today began to take shape in the Baroque era, along with the differentiation between intellectual property rights and copyright. The adoption of the Berne Convention in 1886 lay the foundations for the current intellectual property regime, and led to the creation of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) in the twentieth century.

The nineties were a crucial decade for intellectual property: the popularisation of the Internet led to the proliferation of spaces for creation, collaboration, and consumption of content. New formats and means to reproduce works began to appear, along with new kinds of approaches to licensing and to transferring rights to the production, sale, and enjoyment of intellectual and artistic works.

As a result, the moral rights – the right of disclosure, of authorship, of integrity, of modification, of removal of the work from the market and of access to a single or rare copy of a work –, and exploitation rights – the right to copy, distribute, display, modify, collect, and participate, and the right to receive fair remuneration for private copy – provided by intellectual copyright law had to be revised, as the true scope and effective implementation of the existing legislation was questioned.

Intellectual Property and the New Digital Paradigm

The popularisation of the Internet led to a radical change in the way works are created, produced, and exploited. Websites, forums and blogs use more complex authorship mechanisms than the ones that were around last century. Collaborative writing tools such as wikis have favoured the emergence of new forms of content consumption and distribution that no longer fit the traditional copyright model. The exploitation of intellectual and artistic works weakens traditional business models, and new forms of financing, such as crowdfunding, have appeared.

The publishing contract – the legal foundation of the relationship between the author and the publisher – became full of new ways of implementing rights, and of new formats that are still untested in their operation and scope. It has become necessary to get to know their ins and outs, especially in the case of authors, who have the power to choose what they want to do with their work.

Theories that originally came out of the software market gradually made their way into the world of intellectual and artistic works, and challenged the actual concepts of ownership, exclusivity, and authorship, and, of course, of copyright. This led to the introduction of terms such as open source, copyleft, and freeware in the publishing world, and to the emergence of Creative Commons Licences.

Photo of a printout of the Wikipedia copyleft. Source: Wikipedia.

There was a boom in forms of exploitation of intellectual works, and in the possible services that can be derived from them. These forms of economic exploitation are in turn threatened by free, flexible access to content on the Internet, which also allows wrongful or illegal use of protected works (piracy) and increases the number of people responsible for those uses and abuses.

In the case of e-books, publishers started to implement DRM (Digital Rights Management) systems in an attempt to stop the illegal reproduction of works, even though the technology was based on a closed, complex system that failed to provide protection, and penalised the buyer. A new type of DRM, known as social or “soft” DRM is now starting to prevail, offering greater respect for readers and copyright protection that is non-invasive of the reading and buying experiences.

The interests that were traditionally managed by professional associations are now being reclaimed and exercised by individual authors, who can choose what and how to share. Although self-publishing has not made as much of an impact in the Spanish-speaking market as in the English-speaking world, it is another development that cannot be ignored. Self-publishing is no longer just a trend, it is a tangible fact, an unstoppable phenomenon that affects the heart of the traditional publishing business.

Publishers no longer have a monopoly on book publishing and editing: the emergence of technology companies outside of the book sector have shaken up the industry, and continue to do so. These companies offer free tools that allow authors to publish their own works, dispensing with editors and ignoring the so-called book value chain. Rights are no longer transferred to publishers, they are exercised by the authors themselves.

The response of the publishing sector has been varied, fluctuating between denial and auguring that it is a passing fad on one hand, and trying to find popular figures and authors in these new platforms and bring them into their own catalogues on the other.

In this scenario, the digital environment makes it difficult to establish the boundaries between the author’s ideal interests (personal and moral rights) and his or her material interests over the work (economic or exploitation rights). In Spain, these interests are conditioned by the recently amended Intellectual Property Law.

Kosmopolis 2014: Narrating Google. Search in Google of the book “Crónica de viaje” by J.Carrión. CCCB © Miquel Taverna, 2014.

Recent Amendments to Spain’s Intellectual Property Law

Royal Legislative Decree 1/1996 dated 12 April approves the revised Intellectual Property Law, which is a dynamic legal document: it has been amended over a dozen times in the last two decades. The most recent revision, which came into effect on 1 January 2015, has been criticised for attempting to control the content that is shared on the Internet, and how people share it.

Opponents accuse this legislation – which is also known as the “AEDE levy” and the “Google Tax”, and contains the remains of the so-called “Ley Sinde” – of restricting citizen access to free information, and of favouring the status quo of big corporations. The key to the latest amendment lies in the fact that it affects all Internet users equally, so that an action as natural as linking content between websites could constitute an offence and incur fines.

With the amendment of the Intellectual Property Law, the much-criticised royalty collecting societies once again have the power to charge a private copying levy, which limits the rights held by the copyright owners of the protected works and services.

The types of scenarios described above raise many questions, such as how to exercise copyright in the digital environment without infringing the law, but also without foregoing the collaborative spirit of the Net; how to manage intellectual property while promoting creativity and innovation, without harming the rights of creators, readers, and users; how to interpret the legal loopholes in the legislation, and what mechanisms can be used to adapt the intellectual property model to the digital environment.

The fourth edition of Bookcamp Kosmopolis (2015) probed the Limits of the Book.

Leave a comment