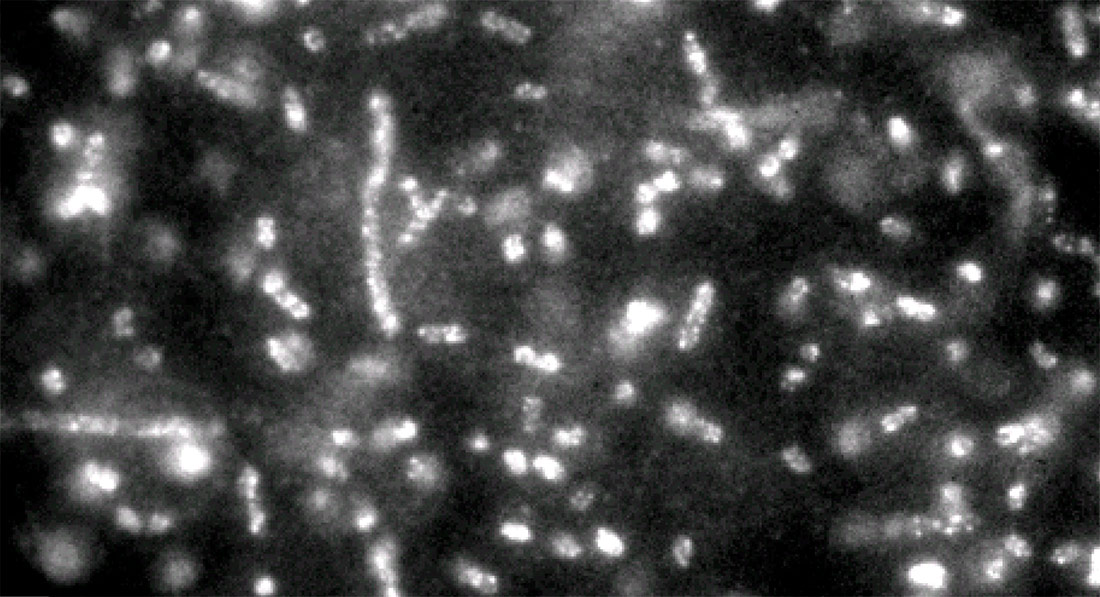

Identifying bacteria with quantum dots | NCI/NIST | Public Domain

The “Quantum” exhibition offers the keys to understanding the principles of quantum physics in the form of a joint creative effort between scientists and artists. Here at the CCCB Lab’s digital magazine, we’ve challenged four artists, with advice from a scientist, to undertake the same experiment: a creative approach to a discipline that has shattered so many prejudices and mental frameworks.

- Seeing things that can’t be seen, a text by Arnau Riera and photographs by Miquel Taverna. With the collaboration of the Atomic Quantum Optics Laboratory (Mitchell Group), Institut de Ciències Fotòniques (ICFO)

- Quantum Meeting No.12, an illustration by María Medem

- Irrelevant Music, an interactive piece by Odil Bright

- The Most Important Lesson, a poem by Martí Sales

![]()

Seeing things that can’t be seen

A text by Arnau Riera and photographs by Miquel Taverna. With the collaboration of the Atomic Quantum Optics Laboratory (Mitchell Group),Institut de Ciències Fotòniques (ICFO)

Going back almost 2,500 years, a handful of Greek philosophers started to ask themselves whether a piece of matter could be continually broken down. Whether a stone, for example, could be broken down into several chunks. Then these chunks could be broken down again. And again and again…

There were two possibilities: either matter could be continually divided into ever smaller pieces or, to the contrary, there would come a point in which the pieces could not be broken down any further. Democritus was in favour of the second option, and he called these indivisible pieces atoms.

Until around a century and a half ago, we had no idea which of these two ways of conceiving matter – continuous versus discrete – was correct. It was simply a question of taste or intuition. If atoms did exist, they were so tiny as to be invisible to the naked eye or even with any type of optical microscope.

All of a sudden, however, a few curious minds started experimenting with gases. By playing around with different volumes, pressures, etc., empirical laws were created for gasses. Surprisingly, these empirical laws for gasses turned out to be the same as those that would apply to a huge number of particles (atoms) obeying Newton’s laws. The kinetic-molecular theory of gasses was born.

And this is how we became convinced that atoms existed without ever having seen one.

Atoms are by no way the only thing we believe in despite a lack of sensory perception. There is a long list: magnetic and electrical fields, radio waves, microwaves, protons, neutrons and electrons, Higgs bosons, gravitational waves, infrared, magnetic moments, polarisations, quasiparticles, and so on.

The history of science is the history of inventing things that can’t be seen in order to explain that which can be seen. We use the laws of physics to build apparatus that allow us to measure with greater precision, allowing us to perform new experiments and discover new phenomena, which force us to come up with new theoretical entities. This ongoing dialogue between theory, experiments and technology speeds up progress.

However, this leads us to what could be an uncomfortable scenario. Could we in fact be building a universe of self-referential knowledge? Could there exist other civilisations that are able to explain nature by means of other abstract entities and laws?

Whatever the answer might be to these questions, we must acknowledge that the edifice of science has so far proved to be harmonious and consistent. It has been astoundingly successful and the way in which it has expanded the power of humans is undeniable.

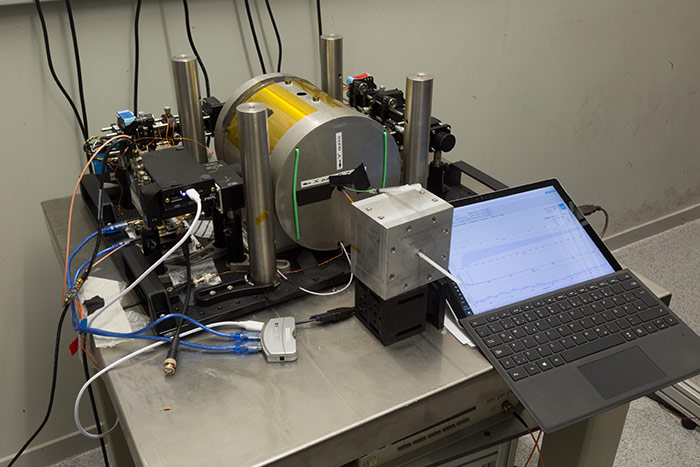

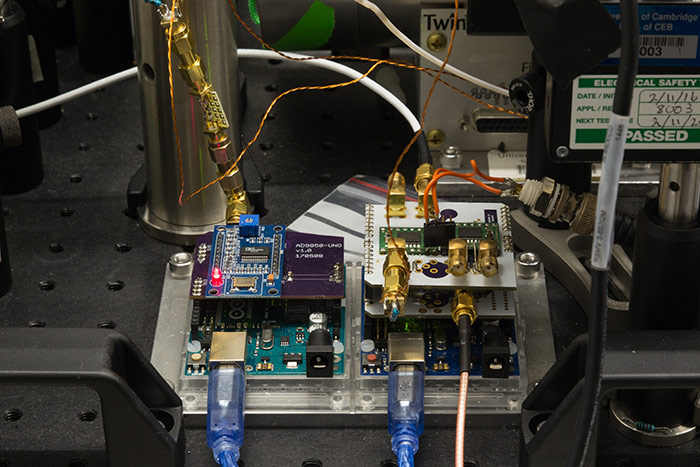

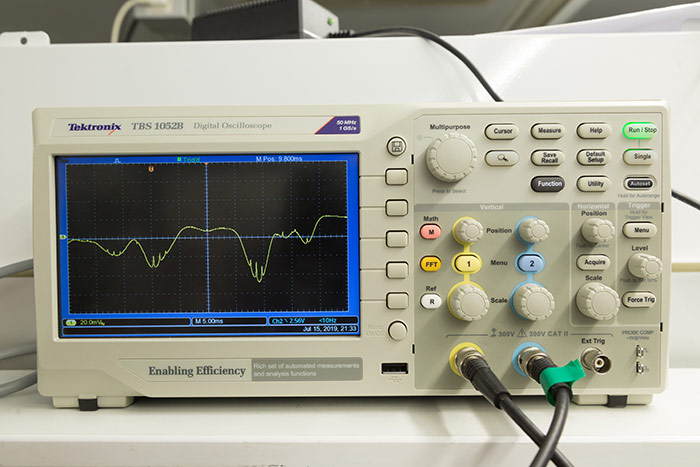

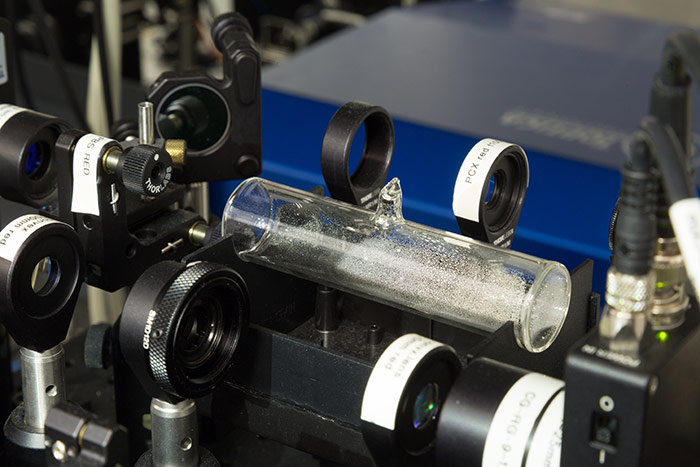

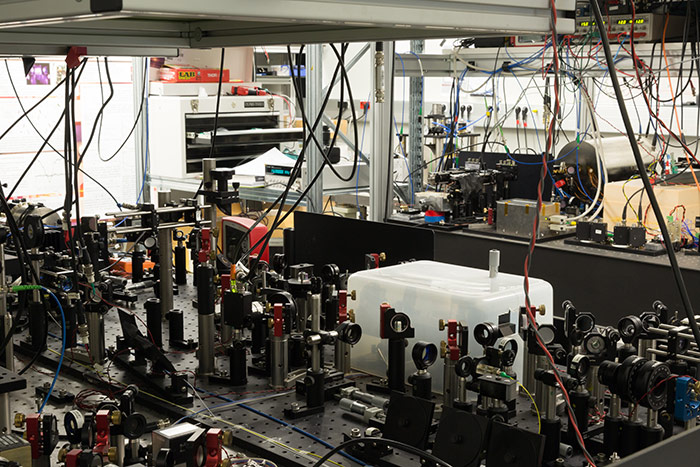

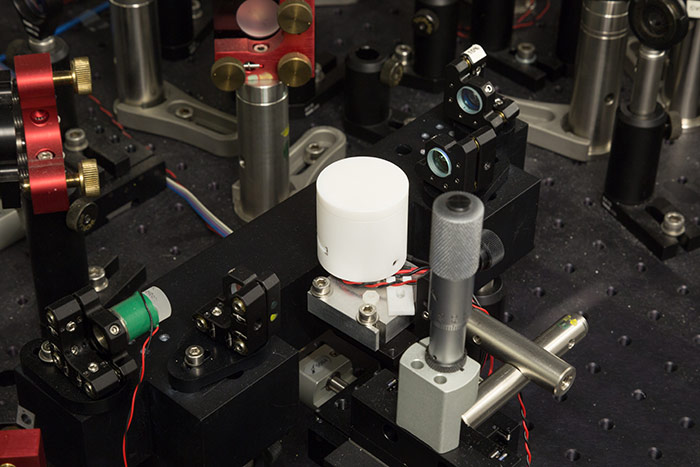

The optical magnetometer used in photography, for example, allows us to measure extremely weak magnetic fields, up to a billion times smaller than the field generated by a fridge magnet. Achieving this prodigious feat of metrology (the science of measurement) is no easy task. It involves a 5-mm cube containing rubidium gas. This gas is lit up with light from a laser which keeps the gas atoms aligned in the direction of the laser. If a magnetic field is present, it will deviate the atoms from this alignment. A second laser can then measure the angle at which the atoms have been deviated, making it possible to infer the strength of the magnetic field. Centuries of scientific knowledge encapsulated in a small piece of measuring apparatus.

The calibration of such apparatus is no small achievement either. It requires sophisticated techniques such as saturated absorption spectroscopy. This technique makes it possible to measure the absorption spectrum of a gas of alkaline atoms with an extremely high resolution, eliminating the broadening of the absorption lines caused by the velocity of the atoms in the gas. Once again, the measurement is performed by sending a laser beam through the gas and recording its intensity on the other side. The data is then processed to give the required information.

To sum up, seeing means measuring. And nowadays, measuring means using extremely sophisticated apparatus that utilise a whole load of physical phenomena the workings of which nobody fully understands. This is the case at CERN, where a single detector will have been built by thousands of people, and it is also the case with the measuring devices used in modern laboratories: saturated absorption spectrometers, optical magnetometers, polarization squeezers… We could say that humans see the world through sophisticated glasses.

![]()

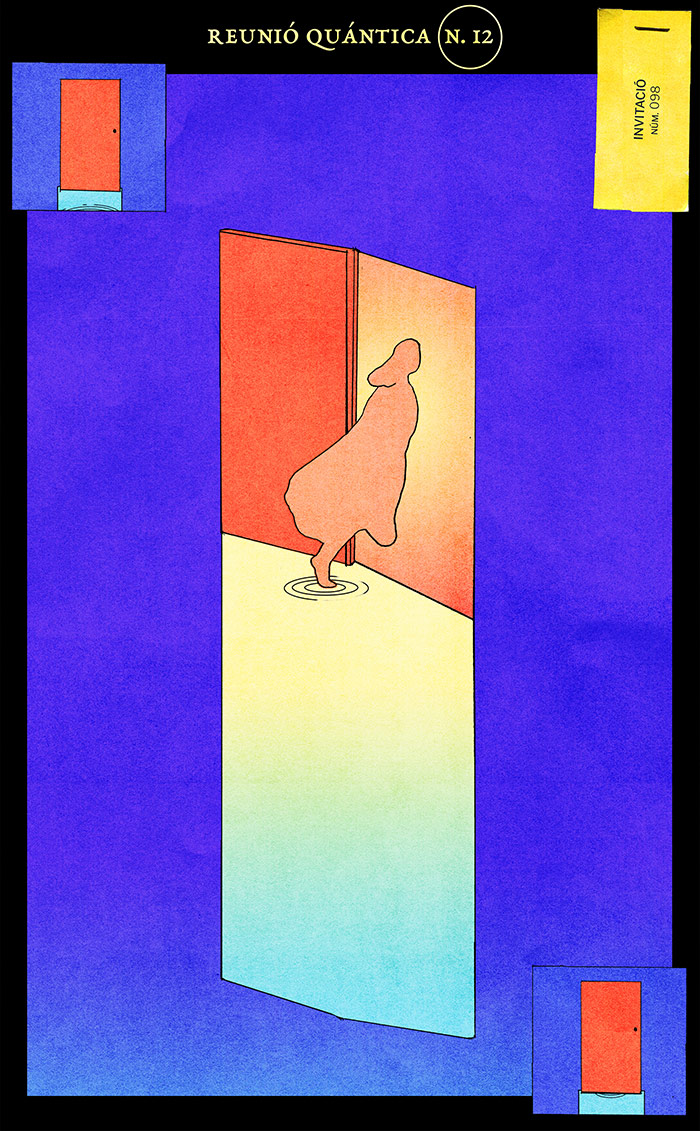

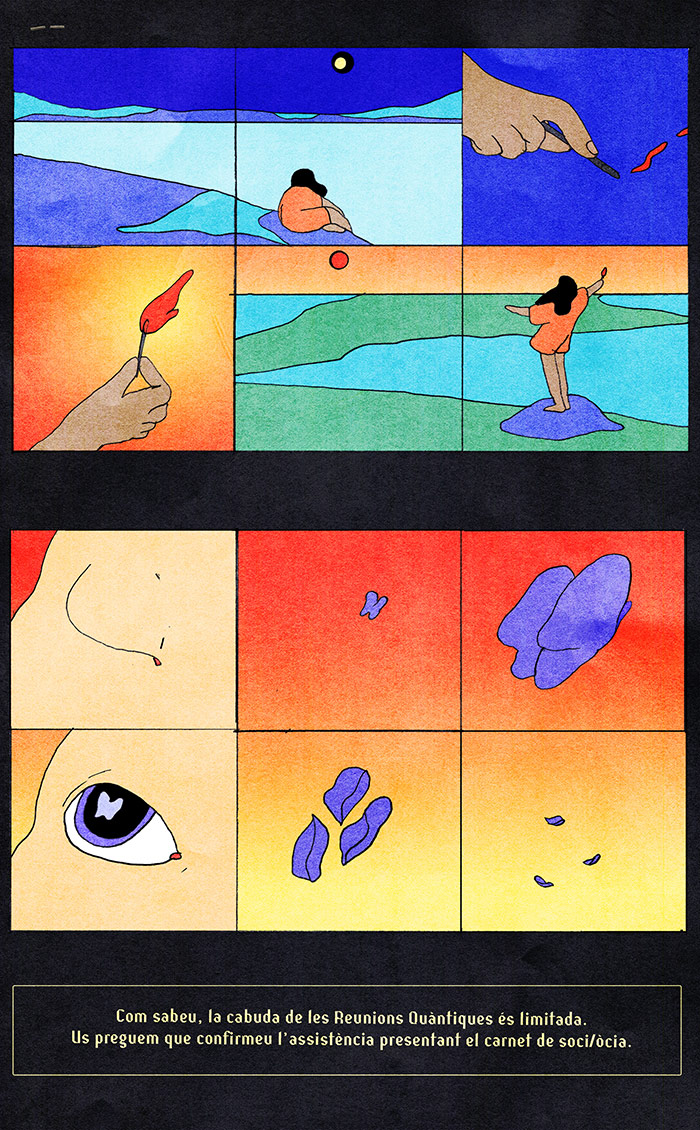

Quantum Meeting No.12

An illustration by María Medem

The idea for the illustration came after reading the exhibition catalogue and understanding that the quantum level is governed by rules that evade the logic we normally apply and according to which everything seemly works. This intrigues me, and I wanted to invent a series of supposed quantum meetings where people would come together in a place where everything was governed by quantum laws. What most caught my attention was the impossibility of measuring things and the fact that, when you observe something, that thing changes.

![]()

Irrelevant Music

An interactive piece by Odil Bright

“The irrelevant process

In general, bias in the selection of elements for a chance-image can be avoided by using a method of selection of those elements which is independent […]. The method should preferably give an irregular and unforeseen pattern of selection.”

G-Brecht (1966). Chance Imagery

“Irrelevant Music” is an interactive piece that draws an analogy between quantum particles and musical notes to question our understanding of musical creation.

When the application is opened, the musical particles exist in a free state, linked together by the same root note chosen at random. However, when we intervene, we force the notes to place themselves within an organised system.

This system or musical state is represented by one of seven modern modes (ionic, doric, phrygian, lydian, mixolydian, aeolian and lokrian). The position in which the particles happen to be at the moment of the intervention determines the order in which the parts of the musical mode will be played: a scale and a chord, created from a root note.

In this way, by applying the principles of quantum mechanics to musical creation, “Irrelevant Music” forces us to reflect on what it means to compose music: in a process in which most of the decisions are left to chance, the subjective expression of the author becomes irrelevant.

Interactive piece developed with Tone.js and p5.js. Irrelevant Music GitHub.

Many thanks to Andy Poole for his help with the software architecture and design.

![]()

The Most Important Lesson

A poem by Martí Sales

Design and animation by Edgar Riu

Language speaks

Things happen

Science delves

What do poems do?

Provide the only sure refuge against the supremacy of the visible world

Things delve

Science happens

Poems speak

What does language do?

Create our world

Language delves

Science speaks

Poems happen

What do things do?

If you pay attention, put you in your place

Language happens

Poems delve

Things speak

What does science do?

Overthrow the dogma of religion and negotiate its axiomatic structure with the humble passion of the researcher. And bombs.

if

light

is the necessary

condition

for seeing

if

light

is a form

of energy

and

changes

excites

what we see

its electrons

when in ‘27

Heisenberg

postulates

that

scientists alter the subatomic

particles

they are investigating

when in ‘27

Heisenberg

postulates

his uncertainty principle

the foundations of physics

crumble

when in ‘31

Gödel

demonstrates

the incompleteness theorem

the foundations of mathematics

crumble

tots both

torpedo

the blind faith

of positivism

to conquer

and dominate the world

have we learnt

the lesson?

in September ‘41

Bohr and Heisenberg

meet in Copenhagen

a Dane and a German

two Nobel prize winners

in a country occupied by the Nazis

the World War

and the responsibility of the physicists

for the atomic bomb

the meeting is short

no one knows for sure

what was said

in August ‘45

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

are wiped off the map

when we carve up light

what is at stake

curiosity

or control

when we want to make the invisible visible

what is at stake

thirst for knowledge

or power

perhaps we should learn the wherefore

of invisibility

and honour it

because the most important

lesson

of quantum

physics

is none of its stunning or destructive applications

the most important

lesson

of quantum

physics

is a lesson

in humility

Leave a comment