Kids with home-made plane, Savin Hill. Leslie Jones, 1934 – 1956. Boston Public Library. CC-BY-NC-ND.

Spain’s public postal company, Correos, is experimenting with providing social services. At the same time, civil servants are joining forces to innovate as a community, citizen groups are co-creating services, and children are designing their own playgrounds with he help of cultural agitators. Even so, some people continue to question whether public innovation is possible. We don’t know the answer, but it’s happening.

Public innovation exists

Every home has a mailbox, and every mailbox has a postman or postwoman – that person who comes by your front door every weekday but who may be on the verge of extinction given that the digital revolution imposes other channels of communication and transport. Nonetheless, the postman was once a key figure in the community. When I was little, for example, we lived in a fifth floor apartment in a building without a lift. The elderly lady who lived opposite timed her trips to the shop to coincide with the postman, who would kindly carry her bags upstairs.

Well, it turns out that Spain’s public postal service company Correos has now decided to remember its identity, and the value that it adds to the community. The company has recently launched a service called Correos te visita (“Correos Comes to You”), in which postal workers are assigned facilitation tasks for the care of elderly persons. As online magazine Cinco Días explains, “they will go to houses where elderly people live alone, to check on their health and spirits, and see if they need anything. They will then inform their relatives via e-mail.”

I mention this case because I consider it a canonical example of public innovation: the company has designed a totally new service of proven value, that makes use of existing knowledge. The post in which Paco Prieto imagines the entire process behind the design of this innovation offers a good overview of the elements that come into play in public innovation.

This case study also offers a clue as to the key to public innovation: it adds value to legitimate recipients. When organizational resources are reformulated in light of knowledge and creativity, and when they have a direct or indirect positive impact on certain sectors of the population, we can consider them public innovations.

Curiously, Correos does not include information on this pilot programme on its website, although it does announce that it is testing the use of drones for deliveries in rural areas. Is this another case of public innovation? Probably, but we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the crucial element is not the use of technology, but the fact that it adds value to society. Technology is too often self-justifying, with a certain fetishist glow.

Public innovation is social

Without going into a conceptual debate about the difference between public innovation and social innovation, we can say that all public innovation is social in nature. And this does not only apply to its purpose – the creation of public value – but also to the way that it is produced. Innovation is people-centred. It is about people having ideas, producing and consuming products and services.

Nonetheless, the organisational structure of the public service sector confines the production of innovation to the political establishment, the management class, and certain departments – modernisation, technology – that are created expressly for the purpose, leaving out all other human talent inside and outside public institutions. But spontaneous innovation emerges from the cracks in the system. In 2013 I published Intraemprendizaje público (“Public Intra-Entrepreneurship”), a book dedicated to the “intra-entrepreneurs” who work in public administrations, where we found that non-conformists who swam against the tide were the origins of most changes.

The public administration is not about to change its bureaucratic structure, at least not overnight. The challenge is thus to set up organisational contexts that favour the emergence of innovation within institutions. We could say that this task involves superimposing “networked meta-structures” over the bureaucratic base. Do we have models that can serve as a guide? Perhaps the clearest examples are the practice communities and learning communities that are springing up in the public sector to promote the collaborative construction of knowledge.

The two best cases close at hand are the Compartim programme run by the Catalan Government’s Department of Justice, and the learning communities organised by the Diputación de Alicante. Both examples are proof that it is possible to officially promote innovation, without stifling the spontaneity that fuels it.

Another example of the emergence of innovation can be seen in networks of public innovators such as Novagob, which has become the most important network of its kind in Spain and Latin America.

Public innovation is open

Public governance in the 21st century is regulated by the paradigm of open government, which revolves around the values of openness and collaboration in the quest for a better, more legitimate public service. Open innovation allows many private companies to optimize their products before launching them on the market. This can also be applied to the public sector, and in this case openness is even more important, given that participation is an inalienable social demand.

As Joan Prats once said “public administration follows society like a shadow follows the body.” Technology has smoothly led society into the age of ubiquitous information. Transparency is no longer optional for the public sector: openness is now a prerequisite.

We are in the midst of some exciting advances in transparency and accountability, but we still lack a clear roadmap for citizen participation and public-private collaborations. The only certainty is that it is worth continuing to build trust between citizens and public administrations.

Innovations usually arise on the margins. The public sector should thus not try to monopolise innovation for social purposes, but instead try offering its support to enterprising social agents, particularly when their entrepreneurship is aimed at the common good.

An example in the cultural world is the fact that some public television stations run by autonomous community governments in Spain spend ludicrous amounts of their budgets on futile attempts to compete with private networks. Wouldn’t it be much better if they were to broaden their outlook and put these stations at the service of local audiovisual sectors? They may not increase their audience share – although perhaps they would, as it would hard to drop far below current levels – but in return we would be nurturing a powerful audiovisual sector. Guess which of the two models produces more social and economic value?

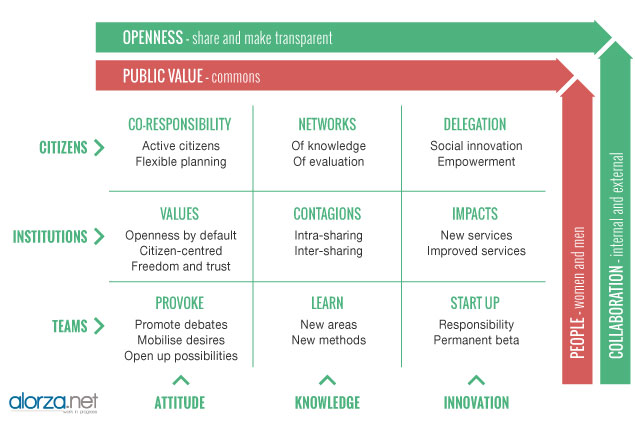

Public innovation model. Alberto Ortiz de Zárate – www.eadminblog.net. CC BY-SA.

Public innovation is learnt

The cultural sector has a lot to contribute to innovation, not just as a site for innovation, but particularly as a social group with a creative attitude and a repertory of innovative routines. Innovation in culture is less important than the ongoing development of the culture of innovation, or enabling contexts that produce emergent innovation.

Our children and young people are being educated in a system that is not making the most of opportunities to innovate in education and educate in innovation. Education is too serious a matter to be left in the hands of schools; the educational system is made up of the whole society, not just parents and teachers. I want to finish this article with an example of a project in which education, creativity, and participation combine to create public innovation and a civic society, through a cultural approach.

Zaramari is a Bilbao-based association that carries out cultural projects based on urban design and social innovation. It has designed the Arkitente programme to introduce architecture to children through schools and centres that organise educational leisure activities.

One of its most comprehensive projects is JolasPlaza. In 2014, the Social Innovation and Participation Department at Portugalete City Council (Bizkaia, Basque Country) contacted Zaramari to commission the co-creation and redesign of a playground in a public square, through a participation process with local children. The process was exemplary, and the results were highly rewarding. It required the generosity of the municipal architect, who was able to delegate responsibility, and of the children’s capacity to produce collective intelligence in a playful dynamic.

I leave you with María Arana from Zaramari, who managed the project in an outstanding manner.

Dani Giménez Roig | 18 February 2016

Alberto, gràcies per aquest magnífic post que m’ha ajudat molt.

A nivell de l’Administració no sé si coneixes l’experiència de les Comunitats de Pràctica de l’Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya.

Vam començar fa gairebé 8 anys inspirats en el programa Compartim del Departament de Justícia però sense que ningú ens fes l’encàrrec, ės a dir, vam néixer de baix cap a dalt…i encara hi som!

http://salutpublica.gencat.cat/ca/publicacions_formacio_i_recerca/comunitats_de_practica/

Leave a comment