Pedro Inoue | © Pedro Inoue

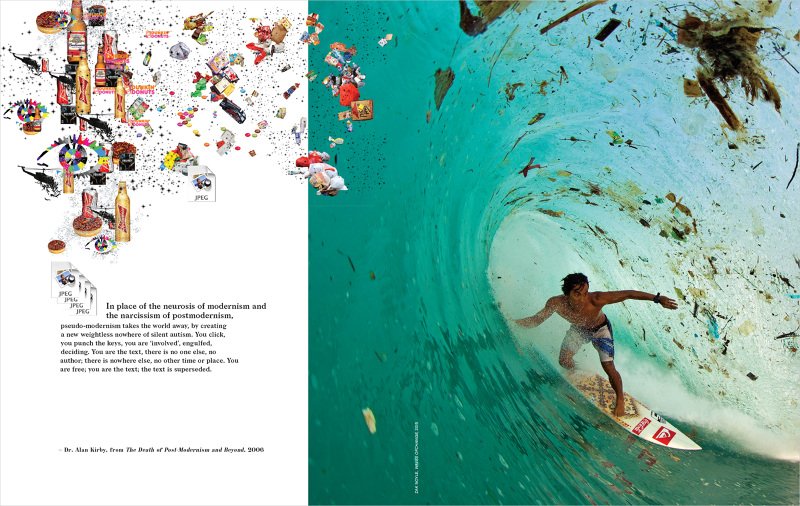

Pedro Inoue is the creative director of the magazine Adbusters which uses the language of mass communication and advertising to criticise the consumer culture. What was originally proposed as an interview ended up becoming a three-month-long conversation via Telegram on codes, culture and politics.

One of the things that show that the debate around the digital versus the analogical may get to be ridiculous is that there are certain experiences that continue to be impossible to transfer from one side to the other. It is impossible to capture in an Instagram story the vibes we felt at a concert featuring our favourite group. It is impossible to transfer a long Twitter thread to an analogical environment and it is definitely impossible to resume in 1,500 words a conversation with Pedro Inoue, creative director of Adbusters.

He’s a person with whom, in a conversation, you can mix (without falling into naivety and without reducing in the slightest its depth in terms of political analysis) issues that range from Kurt Cobain’s suicide to Stranger Things, from Trump as a pop icon to writer T. J. Demos. Pedro Inoue is a book. But not just any book. He’s an overflowing book, full of hyperlinks. From footnotes with their corresponding notes attached to notes. A journey through the political aspect of cultural policies and the cultural aspect of politics.

In May I proposed to Pedro that we do the interview in the following way: I would send him voice messages via Telegram that he would answer asynchronously. I knew that for someone like him who travels so much, this would make it easier to fit the process into his day-to-day life and at the same time, it would allow me a less pressured conversational framework than “a one-hour Skype session”. What I never imagined was that we would be exchanging voice messages for three months until we reached a point where I found myself forced to drop the journalistic formalities of having to call him “Inoue” or “Pedro Inoue” to just call him “Pedro”. But we haven’t come here to talk about our budding friendship. We have come here to talk about Reality™.

“The innocent bystander has ceased to exist”

The starting point for our conversation was the video clip/song This is America by Childish Gambino. Pedro is clear that the initial question to be asked is: How can we NOT talk about Gambino’s This is America?

It gives the impression that is doesn’t matter whether it’s beautiful or ugly. The only thing that matters is that it generates an attraction (…). We live in the attention economy and in the end what this attention and this attraction generate is the need to participate, to discuss, to try to understand what the hell Gambino is telling us. So it’s very interesting because it is all to do with context and not simply with aesthetics. It’s not something that you consume passively. It is clear that the media that we are creating are designed to encourage participation, comment, etc.

In this sense, there is something interesting. The narrative is not so evident. It is designed to be deciphered and to generate that participation:

The really brilliant thing about Gambino’s This is America is that I don’t think that it has a plot. It is more about understanding how the Internet works and arranging in the video different symbols that mean different things to different people. And this is interesting because it is also about with accepting that there will not be one single criticism but thousands in relation to a piece of art. And of course, these people who are participating around the work are continuing it.

Every one of us is invited to participate. And for Pedro, this is proof that something has changed radically: “The innocent bystander has ceased to exist. We are all involved in politics and in the screwed-up world that we are fated to live in. And that is why, nowadays, celebrities and people with millions of followers feel called to take a stand and say what they think about certain types of things. Suddenly you see Leonardo di Caprio sending out environmentally-friendly messages that up to now had been narratives that were discussed by activists and marginal sectors of society”.

“Science fiction can intervene in reality more than reality itself”

It is not complicated for Pedro to glide towards any object of popular culture that can be used as an excuse to talk about political issues. It was inevitable therefore to stop off at The Handmaid’s Tale:

We are really tired of these academic and scientific papers with very normative and serious narratives. We are turned on by fiction because the best criticism to date of the Trump administration has been The Handmaid’s Tale. Writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin and William Gibson produced science fiction based on the world they were living in to go on to then create dystopias or utopias. Perhaps what we must re-think is what role activists want to have in relation to science fiction or even how to be more commercial to make their messages reach other places.

One writer that interests Pedro right now is T.J. Demos. A historian and cultural critic who theorises about contemporary art, visual culture and the relationship of both with globalisation, politics, migration and ecology. Pedro cites him to reinforce the idea that the feminist movement and #Metoo have managed to conquer spaces in society thanks to the fact that they were popularised and became mainstream. “Now we all expect what the feminist perspective is in Hollywood films or it is even starting to be seen in companies. They have become the new normality. What I think is perhaps interesting to underline because it gives food for thought is: why the same has not happened with anti-capitalism?”

“The companies who manage the social media networks are not concerned about the future of humanity, they are concerned with generating more profits”

On shifting the conversation towards how the progressive sectors of society, especially those who were involved in or felt touched by 15M, Occupy Wall Street and other similar movements, did not expect the turnabout that would lead to the victory of Trump, Brexit and other similar events, talking about networks and polarisation is unavoidable. Pedro is clear about his theory: “Today everything is done to make a profit. The more clicks, the more profit. The social media networks are in part a trap because the companies that run them are not concerned about the future of humanity; they are concerned about generating more profits. When people are angry or impassioned, they click more. And in the end, the money that is generated goes to you-know-who.

We live at an accelerated pace. Pedro calls this a “hyper-mode system” in which perhaps it would be a good idea to take notice of those advising that we slow down. “In the first intervention by Comandanta Ramona she said that the Zapatistas were proposing to explore a slower tempo, go back to seeing each other face-to-face, talking, hacking that accelerated system that we live in.” However, this techno-critical utopia does not get along well with reconciliation and I remind Pedro that ultimately, precarity is global, and the digital is sometimes used by those who cannot attend long meetings because they have to take care of other people.

Within the bad news represented by polarisation and these narrative battles, Pedro finds something interesting in it. “I think that the only interesting thing about Trump or Brexit is that these political incidents have drawn red lines. People are more politicised and there are people who are mobilising against white supremacy, against racism or against misogyny, and machismo.” In fact, he believes that this puts citizens in a place where not participating is rather complicated. “The innocent bystander no longer exists. Everything is more obvious. Precisely for that reason I love science fiction: it is a space for thinking about what our future will be”.

Adbusters #120 | Inoue | © Coletivo

“The resistance needs to become more pop”

In the struggle to generate cultural hegemony through narrative and in the online struggle between right and left to see who imposes their narratives, Pedro believes that the left could explore the formats and stories that emerge from popular culture much more thoroughly. Understanding, of course, popular culture as a space where there are contents that travel from the mainstream to activist memes and vice versa.

In this interpretation, the industry is not an infallible machine that always wins and is never affected. What is precisely being demonstrated by feminism is that it is possible to occupy spaces in places where there are famous people, mass narratives, etc. Evidently there will always be contradictions, usurpations, or biased interpretations. But Pedro considers that it is more counter-productive to not accept that we need to make use of those narratives in order to change society. “We live immersed in popular culture. The resistance needs to become more pop. If we think about Star Wars, there are lots of metaphors that could be reinterpreted to generate an activist narrative”.

For Pedro, this rejection on the part of the left to relate to the mainstream and try to maintain discursive purity has done a lot of harm:

I grew up aware of Ché Guevara because he formed part of a Cola drink advertisement. The image has won. That sense of purity, that need to narrate “outside of the system”, I find absurd. As Mark Fisher said, the only place where you can really escape the system and its attempts to squeeze you dry in order to make a profit is when you are dead. I sincerely believe that if it is a case of denouncing a big company because it has stolen an idea, fine, let’s be critical with the mainstream. But when it’s a case of a narrative generated by activists, I think it would be best to abandon the idea of purity and do whatever we can with whatever we have around us. I don’t think there is any other option.

“Perhaps the next great battle should be the environment”

We live in a permanent contradiction in which the digital and technology concern us because they spy on us, they traffic with our data, the polarisation is ever greater… but we are also discovering day by day the power of memes as a political tool for questioning social norms, we are organising ourselves collectively in networks to fight for what we consider just and we carry on weaving a world in common through and despite technology. “We live in a permanent beta and I believe that the key to there being another social change is to be open to it. There is not just one battle, there are thousands.”

Or millions. But ultimately we are finite, vulnerable or interdependent. And without even asking him about it, Pedro himself intuits that, considering that feminism is winning, the next great battle has to be that of the environment. “At Adbusters, we like to stay there asking ourselves which is the next great battle. What is the next message that we can connect. And I see connections between Standing Rock and the feminist protest marches of 8 March. Perhaps the environment is the thing that can connect us all. Perhaps it is the goddam battle of all battles. I don’t know, but maybe it is”.

Adbusters is already a legend in the world of art and activism. But what usually lies behind institutions and brands are people. Pedro is clearly an example of a citizen who is a mix of activist, artist and researcher, a restless agent of civil society who has known how to combine reflection with action and theory with practice, in an exemplary way. And above all, a person who is very clear about the fact that it’s not about generating a narrative that is opposed to the mainstream and the popular, but about playing and experimenting in order to hack the system by infiltrating it with subversive messages using its own language.

Leave a comment